|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Precedent (Australian Lawyers Alliance) |

SELF-DRIVING VEHICLES – WHO’S LIABLE AND HOW WILL THE INSURANCE MARKET RESPOND?

By Owen Hayford

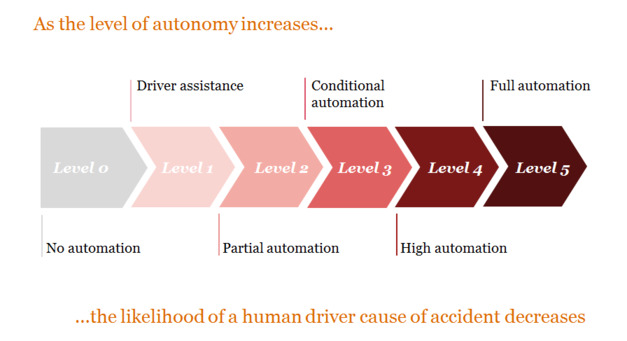

As vehicles become increasingly automated and the role of the human driver diminishes, liability for motor vehicle accidents will fundamentally shift from human drivers to vehicle manufacturers and others involved in the design, manufacture, testing and maintenance of a vehicle’s automated driving system. Insurance arrangements will need to evolve in response to this predicted shift in legal liability, and the funding arrangements for our motor vehicle accident compensation schemes will need to change.

CHANGING LANDSCAPE IN LIABILITY – WHO WILL BE LIABLE?[1]

Today, the most advanced commercially available vehicles include technology that can assist the human driver with steering, acceleration and braking. But the human driver remains responsible for watching the road and, if necessary, taking control of the vehicle. As such, when crashes occur, this is usually because a human driver has been negligent and made an error.

While some crashes are caused by a defect in the way a vehicle has been designed, manufactured or maintained, it is much more common for the cause of an accident to be a mistake made by a negligent human driver. In these circumstances, it is the negligent or ‘at-fault’ driver who is liable to those who suffer injury, property damage or other loss as a result of the accident under our laws relating to negligence.

If we look far enough into the future, to a point where all vehicles are fully autonomous (Level 5) and can perform the entire dynamic driving task without any input from a human driver, it follows that:

● human driver error as a cause of motor vehicle crashes will be significantly reduced if not eliminated; and

● most crashes, in this future world, will instead be due to a failure or defect in the automated driving system.

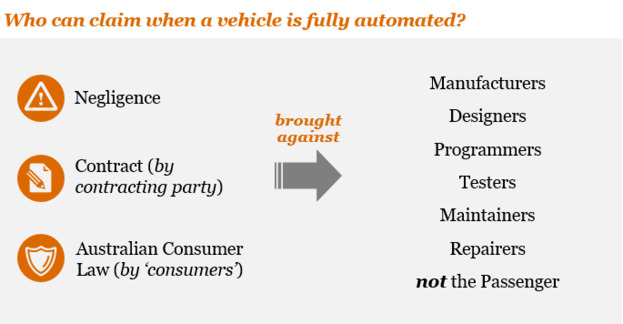

If the defect or fault is due to negligence on the part of an entity involved in the design, programming, manufacture, testing or maintenance of the automated driving system, then any person who is injured or suffers property loss as a result of the crash may have a claim in negligence against the negligent entity. If the injured party is the purchaser of a defective automated driving system, they are also likely to have a claim against the manufacturer or supplier under contract law, and Australian consumer law, by virtue of the automated driving system not being fit for purpose or not being able to perform the driving task with the proficiency claimed by the supplier.

Likewise, consumers who use highly automated vehicles by buying rides or journeys (similar to how Uber works today) may have a claim under contract law or Australian consumer law against the service provider, again based on the service not being fit for purpose or not complying with the marketing description.

But consumer claims can only be brought by consumers. As it stands, passengers or other road-users are not able to make claims under Australian consumer law, or for breach of a contract they are not party to. This means that road-users who suffer injury or loss as a result of a crash with an automated vehicle will need to prove negligence on the part of someone involved in the manufacture or maintenance of the vehicle’s automated driving system to make a claim.

CURRENT STATE OF AUTOMATED DRIVING TECHNOLOGY

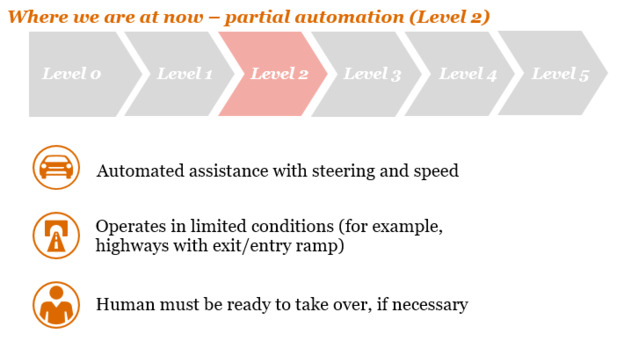

Automated driving technology has not yet progressed to the point of fully automated Level 5 vehicles. The technology that is currently available requires the human driver to play a role in the driving task. For example, the automated driving technology that Tesla presently sells is what’s known as a ‘Level 2’ automated driving system. This level of automation can be used on certain roads to control the vehicle’s steering and speed, but a human driver must constantly watch the road and be ready to intervene if necessary. In the case of Tesla’s Model S, the Tesla owner’s manual says the Level 2 automation should only be used on freeways and highways where access is limited to entry and exit ramps.

UNRESOLVED QUESTIONS OF LIABILITY – FATALITIES INVOLVING LEVEL 2 SYSTEMS

There have been three fatal accidents involving vehicles with this Level 2 technology:

• In 2016 in Florida, a Level 2 vehicle passed under a semi-trailer, shearing off the top of the vehicle and killing its driver.

• In Arizona in March 2018, a Level 2 vehicle hit and killed a pedestrian in a street.

• In Florida in March 2018, a Level 2 vehicle collided with a highway barrier and caught fire, killing the driver of the vehicle.

The first accident has been thoroughly investigated by the US National Transportation Safety Board.[2] The second and third are the subject of continuing investigations.

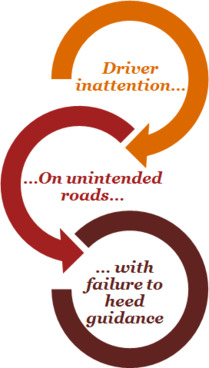

In the first and third cases it appears that driver inattention was a significant contributing cause of the crash. In the second case, video footage[3] of the driver immediately prior to the crash suggests that the driver was not watching the road immediately prior to the collision, but it is possible that other causal factors may have been more significant.[4]

In each case there is a question as to whether there was any negligence on the part of the vehicle manufacturer or any other party involved in the design, manufacture, programming, modification or testing of the vehicle’s automated driving system. Did all such parties discharge their duty of care to those who could foreseeably be harmed by the use of the vehicle? This question is yet to be tested in a court, but it is probably only a matter of time before a person who suffers injury or loss as a result of a crash involving a Level 2 automated vehicle brings a claim in negligence against the manufacturer or others involved in the development and supply of the automated driving system.

Under Australian law, manufacturers owe a duty of care to users to safeguard them against the foreseeable risks of injury when using the product as intended. Retailers and suppliers also have a duty to guard against the dangers known to them, or those which they have reasonable grounds to expect might arise. In the case of a motor vehicle, this duty extends not only to the purchaser but may also include others the manufacturer should reasonably have been aware may be harmed such as drivers, passengers and other road-users.

Accordingly, manufacturers of automated vehicles have a duty to design and manufacture their vehicles with a degree of care appropriate to the dangers associated with the use of the vehicle. They also have a duty to warn prospective users of these dangers. Whether the manufacturer has exercised reasonable care will require an examination of the state of technical and scientific knowledge at the time the vehicle was manufactured and distributed. The greater the risk of injury from the product, the greater the depth of research and testing required.

Importantly, manufacturers and suppliers of motor vehicles owe a continuing duty to purchasers and others to take reasonable care to prevent the vehicle from causing harm – including after the vehicle is sold. Accordingly, a failure to recall a vehicle could also amount to negligence.

US National Transportation Safety Board findings on May 2016 crash

A number of the statements made by the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), in its report[5] into the first fatality, will be of significant interest to any injured party looking to make a future claim against the manufacturer of a Level 2 vehicle:

‘The probable cause of the Williston, Florida, crash was the truck driver’s failure to yield the right of way to the car, combined with the car driver’s inattention due to over-reliance on vehicle automation, which resulted in the driver’s lack of reaction to the presence of the truck. Contributing to the car driver’s overreliance on the vehicle automation was its operational design, which permitted his prolonged disengagement from the driving task and his use of the automation in ways inconsistent with guidance and warnings from the manufacturer.’

On the issue of driver inattention and disengagement, the NTSB’s report raised concerns surrounding the automated driving system’s engagement checking system – it simply checks whether the driver has a hand on the steering wheel, giving little indication of where the driver is focusing his or her attention. The report notes that a driver may touch the steering wheel without visually assessing the roadway, traffic conditions, or vehicle control system performance. The report recommends that manufacturers should develop applications that more effectively sense the driver’s level of engagement and alert the driver when engagement is lacking while automated vehicle control systems are in use.

On the issue of using the automated driving system on roads or in environments other than those for which it has been designed to be used, the NTSB’s report notes that while the manufacturer’s owner’s manual stated that the automated driving system should be used only in preferred road environments, there was evidence that the driver had used the autopilot function on roads for which it was not intended to be used. Accordingly, the driver either did not know of, or did not heed, the guidance in the manual.[6]

The NTSB’s report goes on to recommend that manufacturers of vehicles equipped with Level 2 automation should incorporate system safeguards that automatically restrict the use of the vehicle’s automated driving system to preferred road environments.[7]

These statements by the NTSB could be influential in any future negligence claim against a manufacturer of a Level 2 automated vehicle. They suggest that there may be more that manufacturers of Level 2 automated vehicles could do to guard against the risk of the vehicle being used in an unsafe manner.

Following the crash, the manufacturer has made a number of changes to its automated driving system. In particular, it has reduced the time a driver can have their hands off the wheel before being alerted by the system, and it has provided for the system to be deactivated for an hour, or until ignition restart, if the driver ignores three alerts.[8] But whether it has done enough to discharge its duty of care and avoid a finding of negligence against it remains to be seen.

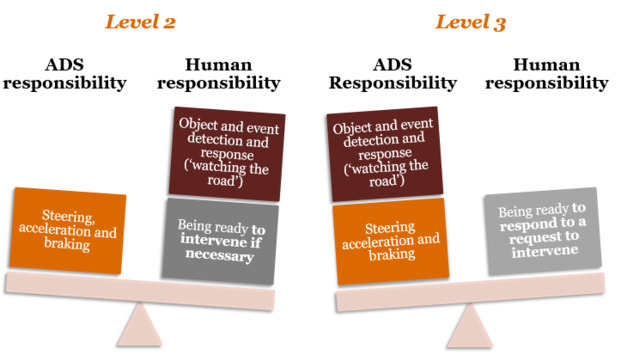

NEXT GENERATION OF AUTOMATION – FROM LEVEL 2 TO LEVEL 3

The shift that we are predicting – where liability for crashes shifts from negligent drivers to negligent manufacturers – will accelerate with the introduction of the next level of automation: Level 3. With Level 3 automation, the task of watching the road and responding to what other vehicles do will shift from the human driver to the automated driving system (ADS).

When a vehicle is operating in Level 3 mode the human driver will be permitted to take his or her eyes off the road for extended periods of time and perform other tasks, so long as they remain receptive to requests from the automated driving system to intervene (for example, as the vehicle approaches the end of the domain in which it can operate in Level 3 mode). If it is the automated driving system, rather than the human driver, that is responsible for watching the road and responding to the movements of other vehicles and the like, then it follows that a failure by the vehicle to avoid crashing into another vehicle will be due to a deficiency in the automated driving system, rather than some error on the part of the human driver.

When Level 3 is used, the ability of the manufacturer to claim that the driver should have been watching the road and taken control of the vehicle so as to avoid the crash will be greatly diminished. Indeed, even if the automated driving system did ask the human driver to resume control prior to the crash, the automated driving system could still be at fault if the time given to the human driver to resume control and avoid the crash was insufficient.

The underwriting risk faced by insurers will become even more complex as we move to Level 3 vehicles. While the likelihood of human drivers being at fault will diminish, the possibility of the human driver being liable will remain. The challenge will be how insurers assess the changing driver-based risk for owners of Level 2 and Level 3 vehicles as they become more common on our roads.

INSURANCE – WHERE ARE WE HEADED, AND WHO SHOULD PAY?

The liability of human drivers in negligence is generally insured by a combination of compulsory third party insurance – commonly known as CTP or greenslip insurance – which covers the driver for his or her liability to others for personal injury or death; and third party property insurance, which covers the driver for his or her liability to third parties for property damage. The premiums for these insurance policies are paid for by the registered owner of the vehicle, who is also usually the regular driver of the vehicle. The insurer will set the premium having regard to, among other things, the driving history of the nominated driver/s.

Manufacturers can insure themselves against their liability in negligence through public and product liability insurance. The premium for this insurance is set with regard to the history of negligence claims against the manufacturer, and the premium is paid by the manufacturer. Similarly, maintenance providers can insure themselves for their liability in negligence through public liability insurance.

As liability for motor vehicle accidents shifts from negligent human drivers to negligent manufacturers or maintainers, the form of insurance product that should respond to claims by those who suffer loss as a result of motor vehicle accidents will shift from CTP and third party property insurance funded by drivers, to public and product liability insurance funded by manufacturers and maintenance providers.

In November 2016, the National Transport Commission (NTC) recommended that state and territory governments undertake a review of compulsory third-party and national injury insurance schemes to identify how they should be amended to remove any barriers to accessing these schemes by occupants of an automated vehicle, or by those involved in a crash with an automated vehicle.[9]

While the NTC’s desire to ensure that those who are injured by an automated vehicle are no worse off in terms of their ability to quickly access compensation is understandable, it does not seem fair or appropriate that human drivers should pay the premiums for insurance that covers the negligence of manufacturers or maintenance providers. We will need to look at a longer term insurance solution that provides appropriate and timely compensation to victims of automated vehicle crashes and is funded on a fair and equitable basis. Indeed, an opportunity exists for Australia to create a better and nationally consistent accident compensation scheme, not just for motor vehicle accidents, but for workplace and other accidents as well.

Owen Hayford is a Partner at PwC Legal. He specialises in the transport and infrastructure sectors. PHONE 0412 664 580 EMAIL owen.hayford@pwc.com.

This article is based on a PwC365 article, ‘Automated Vehicles - Liability and Insurance in the New Age’, first published online on 12 July 2018 at https://www.pwc.com.au/legal/assets/automated-vehicles-liability-and-insurance-in-the-new-age.pdf. The author gratefully acknowledges Con Tieu-Vinh’s assistance with the earlier article.

[1] See also, O Hayford, ‘Self-driving cars – Who’s liable when the car is driving itself?’, Precedent, No. 139, March/April 2017, 29.

[2] See NHTSA reports available at <https://go.usa.gov/xNvaE>.

[3] J R Pignataro, ‘Self-driving uber crash: Likely cause of fatal car accident detailed in report’, Newsweek, 7 May 2018, <https://www-newsweek-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.newsweek.com/self-driving-uber-crash-likely-cause-fatal-car-accident-detailed-report-913407?amp=1>.

[4] Ibid. For many fatalities involving pedestrians, it is the pedestrian that is at fault. For example, the pedestrian may have suddenly walked into the path of the car without looking, such that she would have been hit even if the driver was watching the road.

[5] National Highway Safety Board, Collision Between a Car Operating with Automated Vehicle Control Systems and a Tractor-Semitrailer Near Williston, Florida, May 7, 2016, Highway Accident Report NTSB/HAR-17/02 (Washington DC, 2017) <https://dms.ntsb.gov/pubdms/search/hitlist.cfm?docketID=59989&CurrentPage=1&EndRow=15&StartRow=1&order=1&sort=0&TXTSEARCHT=>.

[6] Ibid, 12, 33 and 33-36.

[7] Ibid, 34.

[8] Ibid, 16.

[9] National Transport Commission, Regulatory reforms for automated vehicles, Policy Paper, Recommendation No. 7 (November 2016) <https://www.ntc.gov.au/Media/Reports/(32685218-7895-0E7C-ECF6-551177684E27).pdf>.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/PrecedentAULA/2018/75.html