University of Melbourne Law School Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of Melbourne Law School Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 12 June 2008

Melbourne Law School

Research Series

Harold Luntz

A View from Abroad[†]

Harold Luntz[*]

Abstract

In Part 3 of its report in 1967, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Compensation for Personal Injury in New Zealand (the Woodhouse Commission) examined common criticisms of the common law action for negligence in relation to personal injury (and some defences of the action). The criticisms included the risk of litigation (the uncertainty of outcome); the reduction of damages if there was any contributory negligence; long delays before the receipt of compensation, if any; the high costs of determining who was and who was not entitled; the need to find a solvent defendant; the adverse effects on rehabilitation; and the inappropriateness of lump-sum awards of damages to provide for long-term incapacity. The Woodhouse Commission concluded that “the time [had] clearly come for the common law action to yield to a more coherent and consistent remedy in the whole area of personal injury” and it recommended “that the Court action based on fault should now be abolished in respect of all cases of personal injury, no matter how occurring”.

This paper examines the continued application of the common law of negligence in relation to personal injury in Australia, with particular reference to decisions of the highest court, the High Court of Australia, in the 21st century. It demonstrates that the criticisms made by the Woodhouse Commission remain valid 40 years later and the arguments for its total abolition are as strong as ever. It contrasts the decisions of the High Court with how similar injuries would be dealt with under the accident compensation scheme in New Zealand.

For pragmatic reasons, the Woodhouse Commission confined its recommendations to accidental injuries. It hoped that other forms of incapacity could be accommodated later. The later Australian Woodhouse Report recommended the extension of the scheme to incapacity caused by congenital conditions and sickness, but that scheme was never implemented. The failure to extend the New Zealand scheme in this way means that some of the High Court decisions on the common law deal with situations on the borderline of the New Zealand scheme and are likely to give rise to similar problems.

Introduction

In Part 3 of its report,[1] the Woodhouse Commission examined common criticisms of the common law action for negligence in relation to personal injury.[2] These included the risk of litigation, in the sense that only a small proportion of claims succeeded;[3] the reduction of damages if there was any contributory negligence by the claimant;[4] long delays before receipt of compensation, if any;[5] the high costs of determining who was and who was not entitled;[6] the need to find a solvent defendant;[7] adverse effects on rehabilitation;[8] and the inappropriateness of lump-sum awards of damages to provide for long-term incapacity.[9] The Commission concluded that “the time [had] clearly come for the common law action to yield to a more coherent and consistent remedy in the whole area of personal injury”; and it recommended “that the Court action based on fault should now be abolished in respect of all cases of personal injury, no matter how occurring”.[10]

This paper will examine the continued application of the common law of negligence in relation to personal injury in Australia, with particular reference to decisions of the highest court, the High Court of Australia (HCA), in this century. It will demonstrate that the criticisms made by the Woodhouse Commission remain valid 40 years later and the arguments for its total abolition are as strong as ever. It will contrast the decisions of the Australian courts with how similar injuries would be dealt with under the Injury Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Compensation Act 2001 (NZ) (IPRCA).

For pragmatic reasons, the Woodhouse Commission confined its recommendations to accidental injuries.[11] It hoped that other forms of incapacity could be accommodated later.[12] The later Australian Woodhouse Report[13] recommended the extension of its proposed scheme to incapacity caused by congenital conditions and sickness, but that scheme was never implemented. The failure to extend the New Zealand scheme in this way means that some of the HCA decisions on the common law deal with situations on the borderline of the ACC and are likely to give rise to similar problems here.

Some statistics

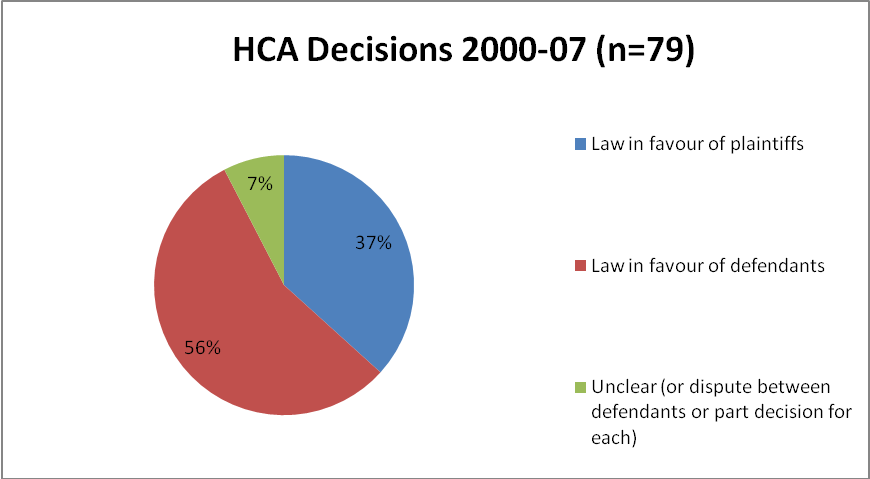

A surprisingly large number of negligence cases have proceeded all the way to the HCA in 2000-07. Seventy-nine decisions during this period have involved personal injuries. In 44 of them, the court has decided the legal issue in favour of the defendant; in 29 the relevant issue was decided in favour of the plaintiff; the remaining six might be seen as neutral. Graphically, the decisions may be represented as on the following chart:

The pro-defendant stance has been attributed by the Chief Justice of Australia to resistance to attempts in recent years by plaintiffs’ lawyers to “push the envelope”.[14] Although this may be true of some of the cases,[15] many merely involved the application of long-standing principles in a way that favoured defendants.[16] In some 46 of the cases, there was at least one dissentient. The outcome merely emphasises the lottery nature of the negligence action.

In para 110 of its report, the Woodhouse Commission illustrated the operation of the common law at the time by describing the two most recent cases then heard before juries in Hamilton. One arose out of an industrial accident; the other from a motor accident. These would have been the types of accident most frequently, if not almost entirely, coming before the courts, at the time. They are still common in the cases that reach the HCA, though they no longer predominate as they once did.[17] This paper will start by considering some of these, taking motor accidents first.

Motor accident cases

A comparatively rare case of unanimity in the HCA is to be found in Derrick v Cheung.[18] The court acknowledged that the facts of the case were tragic and that the trial judge had accurately described them as “a parent’s worst nightmare”. A 21-month old child wandered into the road and was run down while her mother was talking to a friend. The trial judge found the motorist to be negligent, a finding upheld by a majority of the NSW Court of Appeal, though it offered the defendant the “consolation” of stating that she was not morally to blame (and, of course, she would not personally have to pay the damages, since her compulsory third party insurer would). The HCA held that to introduce the notion of moral blame was to obscure the real issue, which was “to determine the issues according to law: in this case, by not finding an absence of care in circumstances in which reasonable care was ... in fact being exercised”. The child’s action accordingly failed.

One much criticised aspect of motor accident cases at the time of the Woodhouse report was the problem of determining many years after the event whether the defendant had indeed failed to exercise reasonable care. By their nature motor accidents tend to happen quickly and evidence in court is often more reconstruction than accurate recollection. In Derrick v Cheung the HCA decision was handed down 6.64 years after the date of the accident. In another motor accident case in the HCA, Fox v Percy,[19] the most highly-paid judges and, arguably, the best judicial minds in the country — assisted by two QCs and two junior barristers, briefed by two of Sydney’s leading law firms — devoted an afternoon examining skid marks in order to decide on which side of the road a collision occurred between a motor vehicle and woman riding a horse, a process at least one journalist described as astonishing. Even more astonishing to the journalist was that this happened 11 years after the accident.[20] The ostensible reason for this exercise was to lay down the principle on which an intermediate appellate court should interfere with decisions given at first instance. In the end, the decision went in favour of the defendant. So did the decision in Commissioner of Main Roads v Jones, where the HCA more than 13 years after the accident restored the trial judge’s decision, which had been reversed by the WA Full Court.[21]

As with any lottery, there are some winners. For example, in Anikin v Sierra,[22] the plaintiff, who having got lost was walking on a dark road at night when he was run down by a bus, ultimately succeeded in the HCA by a majority of four to one. So, too, in Manley v Alexander,[23] the plaintiff succeeded, when a narrow majority of the HCA upheld the decision of the WA Full Court, overturning the decision of the trial judge. The latter had exonerated the defendant of negligence in running over the plaintiff, who was intoxicated and lying in the road at 4.15 am. But both these “lucky” plaintiffs paid the penalty of substantial deductions for contributory negligence, 25% in Anikin and 70% in Manley. Furthermore, they had to wait 7.7 years and over 5 years from the date of the accident respectively until they knew whether they would receive any compensation at all. Another case that took 7.7 years from the accident to final resolution by the courts, with a trip to the HCA on the way, was Joslyn v Berryman.[24] In this case the HCA held that the NSW Court of Appeal should not have set aside a finding of contributory negligence on the part of a passenger who, on the way to obtain breakfast, handed over the driving to a companion whom he should have known was still intoxicated from the previous night’s carousing. The HCA remitted the case for further consideration of the degree of responsibility to be attributed to the passenger and the Court of Appeal then increased the trial judge’s attribution of 25% to 60%.[25] Thereafter, the matter came again before the Court of Appeal on an issue as to costs.[26]

In Joslyn v Berryman the passenger sued not only the driver, but also the local authority on whose road the accident occurred. It is not unusual for persons injured in motor accidents to seek a defendant other than the driver of a vehicle, either because the plaintiff was the driver in a one-car accident (as in Commissioner of Main Roads v Jones) or because an attempt to prove that a driver was at fault fails. Thus, in South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd v Cole[27] the NSW Court of Appeal set aside a judgment finding that the driver of a vehicle was negligent in running down the plaintiff, but the action against the club at which the plaintiff had been drinking proceeded to the HCA.[28] There, two judges held that the club did not owe the defendant a duty of care to protect her from the consequences of her own drinking; two judges held that, if they did owe her a duty of care, they were not in breach; and two judges held that the club was liable to her.[29] The plaintiff was left remediless.

Another incentive to seek a defendant other than a motor vehicle driver is that in some jurisdictions at different times legislatures, in an attempt to keep compulsory third party insurance premiums down, have restricted the damages recoverable from such insurers, while not restricting the damages recoverable from others. One such case was Pledge v Roads and Traffic Authority,[30] where the dispute that came before the HCA was among the three defendants. While in this case the time from the date of the accident to the decision in the HCA was under just 10 years, the resolution of the damages issue took another year and a further decision of the NSW Court of Appeal.[31] One hopes that the plaintiff, who was a child when injured and an adult when judgment was finally given, was not kept waiting all the time for her compensation.

One final example of the harsh operation of the common law in relation to motor accidents is Batistatos v Roads and Traffic Authority of New South Wales.[32] Callinan J opened his judgment with the following words:

This appellant has had a most unfortunate life. The first of his many misfortunes was to be born mentally retarded. The second was to lose his mother when he was one year of age. The third was his separation from his siblings and his admission to a mental institution when he was six years old. Another, in 1965, was to be rendered quadriplegic in a motor accident when the vehicle that he was driving failed to take a bend in the road and overturned. The last was to have an action which he brought in the Supreme Court of New South Wales to recover damages in respect of his quadriplegia, brought within the limitation period, stayed by the Court of Appeal of New South Wales, on the basis that effluxion of time alone produced the consequence that the action could not be fairly tried.[33]

By a majority of four to three, the HCA visited further misfortune on the plaintiff by dismissing his appeal.

Apart from this last case, where the accident would have preceded the coming into force of the ACC, all the above cases would have presented no problem whatsoever if their facts were replicated in New Zealand. All the injured parties would have had cover under the various incarnations of the scheme that emanated from the Woodhouse report and would have received their first payments of compensation within days. Contrast the sorry tale of one unfortunate New Zealander, described in the judgment as being “of Maori extraction”, who went on a working holiday to Australia in 1976. On 13 July 1978 he was injured in a motor accident in South Australia. He suffered severe brain damage and was left barely conscious. The Public Trustee was appointed to represent him in litigation. An agreement was reached that the plaintiff had to accept a 30% reduction in damages on account of contributory negligence. Damages were eventually assessed by the court on 7 August 1992, 14 years later, at $761,022 after the reduction for contributory negligence. An appeal led to an increase in the damages, including interest, to $856,922.[34] Thereafter, the plaintiff’s costs were taxed at about $361,000. Disputes as to costs and interest on them came before the courts several times,[35] including an application to the HCA for leave to appeal, which was refused on 10 August 2000, no doubt incurring further costs. A taxing master made some further errors in dealing with the costs and the defendants again brought the matter before a single judge of the Supreme Court, who remitted it back to the master.[36] Thus, some 23 years after the accident, the case had not been finally resolved and the costs on both sides probably far exceeded the damages.

No doubt this case is exceptional, but probably not unique. In 1996 I wrote an Editorial Comment on the medical negligence case of Rogers v Whitaker,[37] in which I observed that litigation concerning the tax consequences of the interest included in and after her judgment for a little over $800,000 in respect of total blindness revealed that her costs alone were almost $350,000.[38] Recently, in a case brought before the HCA for special leave to appeal against a judgment for a child plaintiff in a horse-riding accident, the four judges of the NSW Supreme Court having been equally divided on the liability of the defendant, the HCA approved a settlement in which the only money that changed hands was a payment of $100,000 by the defendant towards the plaintiff’s costs. Heydon J commented that if not for the settlement the outcome could have been far worse for the plaintiff.[39]

New South Wales in 2006 introduced no-fault provisions providing lifetime care and support for people who suffer “catastrophic injuries” in motor accidents. In introducing the legislation, the relevant Minister said that “[u]nder the current Motor Accidents Compensation Act only 65 of the 125 people catastrophically injured in a motor vehicle accident [annually in NSW] are likely to be eligible for compensation”.[40] Similar proportions would probably apply in the remaining Australian jurisdictions without no-fault motor accident schemes (Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia). The Minister also made the point that “[e]ven those in receipt of compensation are not guaranteed a lifetime of reasonable care and medical treatment”. Apart from contributory negligence, which may account for this, this point goes to the issue of the adequacy of the lump-sum form of compensation that is awarded at common law. I have dealt with this latter point elsewhere and will not repeat the criticism of the common law in this respect in this paper.[41] I shall merely say that structured settlements have not provided an answer.[42]

At the same time as introducing legislation to make provision for lifetime care of those catastrophically injured in motor accidents, New South Wales passed legislation for so-called “blameless” motor accidents and for cases where children are injured, such as in Derrick v Cheung. This came into operation very recently, on 1 October 2007, and it is too soon to see how well it will work. It will not cover drivers who themselves cause accidents and the benefits for children are very limited. It would seem to continue the lottery aspect of motor accident compensation in favouring some victims over others. This is true also of the no-fault schemes operating in Victoria and Tasmania. When the current no-fault motor accident scheme was introduced in Victoria, the government hoped to model it on the report of the NSW Law Reform Commission,[43] which contained a comprehensive criticism of the common law action and recommended its total abrogation. However, at the time, the Victorian government did not have a majority in the upper house of Parliament and was forced to compromise in the legislation, the Transport Accident Act 1986 (Vic). This compromise allows motor accident victims who surmount a narrative threshold, so that their injury satisfies a statutory definition of “serious”, to claim limited damages at common law. One of the continuing problems that besets the courts in Victoria is to distinguish those persons injured in motor accidents whose injuries are “serious” and who are thus entitled to recover damages if they can prove fault.[44]

Industrial accidents and diseases

For about a century all Australian jurisdictions have had no-fault workers’ compensation schemes. However, until fairly recently, the option of suing at common law was retained. Now several jurisdictions have made the no-fault compensation under the legislation the exclusive remedy against the employer or have restricted the damages recoverable in common law actions against the employer. This has encouraged workers to seek remedies against third parties in the hope of recovering larger amounts by way of damages. At least two such cases have reached the HCA in consequence. In the first of these, Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil,[45] the HCA, with one dissent, reversed the two lower courts, which had held the occupier of the shopping centre where the plaintiff worked liable for injuries sustained when he was attacked by unknown persons in the centre’s car park as he made his way to his car after work when the lights had already been turned out. Such an assault in New Zealand would come within the general provisions for cover of IPRCA s 20(2)(a) as “personal injury caused by an accident to the person”. Intentional attacks on workers have from the earliest days of workers’ compensation been treated as unexpected events from the workers’ point of view and therefore “accidents”.[46] New Zealand in fact pioneered criminal injuries compensation and the Woodhouse report recommended that “[t]he general basis for protection should be bodily injury by accident which is undesigned and unexpected so far as the person injured is concerned”.[47] ACC statistics show that 7657 claims were accepted for injuries resulting from criminal acts (other than “sensitive” claims) in the past 11 years.[48] Those who have cover would have no right to claim damages from anyone else.[49]

In the second of the two cases referred to above, Slivak v Lurgi (Australia) Pty Ltd,[50] the plaintiff again failed in the HCA with one dissentient when seeking to hold the designer of the structure on which he was working liable. Callinan J, while purporting not to comment on the policy of the legislature in removing the right to sue the employer, suggested that the effect of the removal might be reduce the incentive on employers to make the workplace safer.[51] The Woodhouse report specifically noted this argument in favour of retention of the common law,[52] but found it impossible to accept. Compulsory insurance is likely to remove any deterrent effect of an actual award of damages. While it is often contended that adjustment of insurance premiums provides an incentive for employers to take more care, the empirical evidence for this is largely lacking[53] and it may have adverse effects.[54] Furthermore, there are huge difficulties in applying experience rating to small firms and in respect of long-delayed findings of fault.[55] Prior risk-assessment by insurers and insistence on the taking of precautions in return for reduced premiums is likely to be more effective. Whatever incentives are applied to employers insured against common law liability can equally be applied to the no-fault elements of any scheme.[56] A systemic approach to accident-reduction, which is the favoured approach today,[57] can best be devised by a single insurer, such as the ACC, which collects and analyses all the data.

Despite his belief in the efficacy of the common law in making the workplace safer, Callinan J joined the majority of the HCA in Liftronic Pty Ltd v Unver,[58] where a jury’s verdict reducing the plaintiff’s damages by 60% for contributory negligence was restored, despite the NSW Court of Appeal having found it to be perverse and having substituted a reduction of 20%. Contributory negligence may also substantially reduce the damages recoverable by independent contractors seeking compensation from occupiers, as in Thompson v Woolworths (Q’land) Pty Ltd.[59] Here, the plaintiff injured her back when she pushed a heavy refuse bin out of her way while delivering to a supermarket. The intermediate court of appeal set aside the trial judge’s finding of negligence on the part of the supermarket. The HCA restored the finding that the defendants were negligent, but subject to a reduction of the damages by one-third for contributory negligence.

The way in which work is carried out in Australia has changed since the days of the Woodhouse report. There is now increased outsourcing of work that would previously have been performed by employees. Former employees may do exactly what they did before, but are now formally employed by their own companies or by labour hire companies who hire them out to the former employers. What may have once been relatively simple common law actions to determine whether employers were at fault may be transformed into complicated disputes on the share the various parties are to bear, if any,[60] with the strong chance that the injured worker will lose somewhere along the line. One such case that reached the HCA is Andar Transport Pty Ltd v Brambles Ltd.[61] In this case, the plaintiff was originally employed by Brambles, but was required by Brambles to form his own company and tender for the work he previously did as an employee. He did so successfully. He was injured while moving a heavy trolley supplied by Brambles. He sued Brambles and recovered damages reduced by 35% for contributory negligence. Brambles then sued the plaintiff’s company for indemnity or contribution. The HCA held that the plaintiff’s own company was liable to the plaintiff and could therefore be sued by Brambles for contribution. Perhaps this was merely a dispute between insurers as to how much of the plaintiff’s damages each to was to bear, but potentially the plaintiff would effectively suffer a further reduction in his damages by virtue of payment from his own company.[62] A similar problem confronts a member of the public injured by such a worker in sheeting home vicarious liability to an employer.[63]

Complications abound in New South Wales because of the different levels of damages recoverable from the employer and from third parties, which are exacerbated by the “murky waters”[64] of the Workers Compensation Act 1987 (NSW) s 151Z in relation to the rights of the defendants to recover contribution from each other,[65] especially when a compulsory third party motor insurer (or the nominal defendant) also becomes involved.[66] Cases may reach the HCA simply on the issue of which insurer should bear the loss, though how much the injured worker is to receive may also depend on the outcome.[67] Although it is impossible to see any good coming from these disputes, the cost to the community through insurance premiums of all types is huge. These particular types of dispute are largely avoided in Victoria by having a single fund as the statutory insurer and providing legislatively for disputes between that fund and the motor accident fund.[68] However, the reinstatement in that state of the right to sue at common law for “serious” injuries provides the courts with plenty of work in discriminating in favour of some workers and against others, just as in the case of motor accident victims referred to above.[69]

Contribution claims also occupy the Australian courts in many cases of industrial disease, such as where workers have developed asbestos-related diseases after exposure to asbestos during their employment. The HCA has not yet considered expressly the issues raised in the two decisions of the House of Lords of Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd[70] and Barker v Corus (UK) Plc,[71] which held that workers who developed mesothelioma but unable to prove which exposure in their working lives actually caused it, could recover proportional damages from each tortious defendant. However, similar disputes have come before the lower courts and so far the HCA has refused leave to appeal on the issues.[72] They are sure to come up again.[73] In McPherson’s Ltd v Eaton[74] a worker succeeded against a number of defendants at first instance, but was deprived of his judgment against the retailer on appeal on the basis of an absence of a duty of care. Although an editorial note to the report refers to an application for special leave to appeal to the HCA having been filed by the plaintiff against this dismissal of his claim against the retailer, the application must have been withdrawn, since the plaintiff apparently retained judgments against other defendants.[75] Just before the turn of the century the HCA did provide a remedy for stevedores employed by different employers on a daily basis by holding, by majority, that the authority that allocated them to the particular ships owed them a duty of care.[76]

Whether or not there are any problems for the ACC in allocating particular claims to the accounts in which the funds are kept, none of these cases should arise in New Zealand. The victims would all have cover in the ordinary accident cases under IPRCA s 20(2)(a) and would receive their benefits immediately. The disease cases, particularly those of long latency, may be a little more complicated, but would probably be satisfactorily dealt with under ss 20(2)(e) and 30 and Schedule 2, especially after the amendments proposed by the Injury Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Compensation Amendment Bill (No 2) 2007 (NZ) cl 10, which will ease the difficulty of proving the causal link between the work and the disease. However, not all New Zealanders have been deterred from attempting to recover damages in Australia from the manufacturers of asbestos to which they have been exposed in New Zealand. In several the plaintiffs have not been allowed to proceed with their actions, even after seeking leave to appeal to the HCA.[77] Where, however, the plaintiff was injured aboard a New Zealand ship tied up in Sydney harbour, the common law action was allowed to go ahead in New South Wales under the law of that state.[78]

Occupiers’ liability

The common law laid down rigid standards of care owed by occupiers to different categories of entrants on to the land. This led to frequent disputes as to the categorisation of particular entrants and the application of the relevant standards. New Zealand, following statutory modifications of this regime elsewhere, reformed the law in relation to some of these categories with the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1962 (NZ). Although still on the statute books, this Act must have become a dead letter with regard to personal injury once the ACC scheme came into operation. Some Australian states also enacted occupiers’ liability legislation, but the HCA went further in eventually largely sweeping away the categories and laying down a general duty of reasonable care in the circumstances.[79] However, minds can easily differ as to what is reasonable care in the circumstances and thus cases continue to come before the HCA. In Neindorf v Junkovic[80] the plaintiff was injured when she tripped on the driveway of a house in which a garage sale was being held. The case went through four levels of courts: the plaintiff succeeded in the magistrates’ court, whose decision was reversed by a judge of the Supreme Court of South Australia, who was in turn reversed by a majority of the Full Court of the state, which decision was in turn reversed by a majority of the HCA. If you have kept track of that, it means that the plaintiff finally lost and so went remediless.

A similar reversal at each of only three stages occurred in Hoyts Pty Ltd v Burns,[81] where a teacher’s aide looking after disabled children was injured when she sat down on a seat that had retracted. Again, she lost in the end. Compensation awarded for an injury caused in similar circumstances was taken away on appeal in another case; this time the HCA did not give leave for a further appeal.[82]

We have already noticed two cases in which attempts to extend the occupiers’ duty of care beyond the condition of the premises failed, in each instance by a majority: Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil[83] and South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd v Cole.[84]

Every one of the five plaintiffs who failed in these Australian cases would have had cover in New Zealand.

Landlords

Landlords at common law were not treated as occupiers of their land and enjoyed immunity from liability in tort towards the tenants and their families.[85] Occupiers’ liability legislation, where enacted, changed this.[86] Australian common law on the subject also evolved, so that the immunity was not even relied on when the child of a tenant was electrocuted when she touched a tap in the garden which had become live as a result of a faulty repair to a stove in the house carried out by an independent contractor. She succeeded in the HCA in holding the landlord liable, but her victory was only by four to three and the majority judges were divided two all in their reasoning.[87] The uncertainty thus created had to be dispelled quickly and the HCA gave leave to appeal in a case where the son of a tenant cut his leg badly when a glass door into which he walked shattered. While clarifying the law to some extent, the majority of the court denied a remedy to the plaintiff.[88] Both these plaintiffs would clearly have had cover in New Zealand.

Slips and falls on the highway

Another immunity conferred by the common law was on highway authorities in respect of “non-feasance”, or omissions to repair or remove dangers in the fabric of highways under their control. The law had become so riddled with exceptions and fine distinctions that a narrow majority of the HCA in Brodie v Singleton Shire Council[89] overturned years of authority and held that the ordinary law of negligence applied. This led to a spate of actions by pedestrians who had fallen and injured themselves on highways. Two issues in particular made for disagreement among the lower courts. A dictum in the joint judgment of three members of the majority in Brodie in relation to an associated appeal in which the court unanimously dismissed the action of a pedestrian stressed the importance of formulating the duty so as to “require that a road be safe not in all circumstances but for users exercising reasonable care for their own safety”.[90] This has been interpreted by some courts as denying any duty of care towards pedestrians who were not exercising such reasonable care,[91] whereas other courts preferred the view that a failure to exercise reasonable care for one’s own safety went merely to factual issues of breach and contributory negligence.[92]

The other issue is the purely factual one which always emerges when the common law requires determination of what is “reasonable”. It was always recognised that pedestrians could not expect “bowling greens” wherever they walked,[93] but often the outcome seemed to be determined by whether a raised area of a footpath did or did not exceed 20 mm.[94]

An Australian report into the burden of falls of elderly people leading to hospitalisation deplores the lack of availability of data on the circumstances of the injuries.[95] However, a table, “Place of occurrence for fall injury incidents, males, females and persons aged 65+ years, Australia, 2003–04” records that of a total of 60,497 such falls, 2693 occurred on streets and highways.[96] In the argument for special leave to appeal in one of the tripping cases, which was refused, counsel referred to some statistics which stated, under the heading “Persons 65 Years And Over Who Have Fallen In The Last Twelve Months”, that “Uneven/cracked man-made surfaces” were responsible for 16,500 incidents. Callinan J, however, commented that in percentage terms, the figures did “not suggest that it is a very big problem”.[97] Whether or not the falls that occur on highways are “a very big problem”, they, like all the other falls, would be covered by the ACC and there would be no need to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars determining whether a small number of those who fall should receive common law compensation, while the others received nothing.

In any event these developments in the common law have not been allowed to continue unabated. Legislatures in the Australian jurisdictions have restored to some degree, though not completely, the former immunity enjoyed by highway authorities.[98]

Sport and other recreational injuries

New Zealand, of course, is a rugby-playing country. The ACC statistics reveal that over 3000 new claims have been accepted in each of the past 10 years for injuries incurred in rugby union games. In 2005-06 there were 930 of such claims still ongoing, at a cost of $NZ16,402,000.[99]

Contrast that with the litigation that led to the decision of the HCA in Agar v Hyde.[100] Two men, aged 19 and 18 at the time, broke their necks playing rugby union. They were injured while playing hooker (the middle position in the front row of the scrum) for their respective teams. In consequence, both became quadriplegic. They sued a range of different defendants, including the members of the International Rugby Football Board (IRFB), an unincorporated body responsible for making the rules of the game. They alleged that by the date of their injuries, 1986 and 1987 respectively, there was a body of evidence of the dangers to hookers from the manner in which the members of the opposing teams who formed scrums came together. They contended that the members of the IRFB owed them a duty of care to amend the rules so as avoid these dangers. They pointed to the rules having in fact been amended in 1988 to require a phased engagement of the two opposing front-rows of the scrum in a regulated sequence in which each of the front-rows crouch, touch, pause and only then engage. Different aspects of the case came before three different judges in the NSW Supreme Court. One judge held that the plaintiffs could not succeed against the members of the IRFB because they owed them no duty of care. The NSW Court of Appeal reversed the decision, holding that it could not be said that no duty of care was owed until all the evidence was in. The members of the IRFB appealed successfully to the HCA, whose judgment was handed down just under 13 and 14 years respectively from the dates when the two boys were injured.

Although the case was criticised,[101] and dealt essentially with procedural matters, judges in New South Wales have considered it indistinguishable and held that local boards do not owe a duty of care so to organise and regulate the playing of the game as not to expose players to unnecessary risk of injury.[102] Understandably, seriously injured players continue to look for some defendant, be it another player, the referee or one of the clubs, to sue in order to provide them with compensation.[103]

Australians and New Zealanders share a love of cricket. The ACC statistics show that during the last 11 years, almost 4600 claims have been accepted for injuries arising from all forms of the game. Over 1000 of these resulted from indoor cricket.[104] None of these people would have had to face the problems of Mr Woods, who suffered a serious injury to his eye while playing at a commercial indoor cricket venue and in the end lost his claim for damages by three judges to two in the HCA.[105]

It has been Australians’ love of swimming that has given rise to most problems for the common law in recent years.[106] On 7 November 1997, a young man became a quadriplegic when he struck his head on a sandbank at Sydney’s iconic Bondi beach. When a jury found that the local council was liable in negligence, the Premier of New South Wales announced on the beach itself that legislation was to be introduced to curb liability.[107] The decision was subsequently reversed by a majority of the NSW Court of Appeal, but restored by the HCA on 9 February 2005 in a three to two decision. Other young men and boys severely injured when diving or jumping into the water have not had Mr Swain’s “luck” in the courts: see Vairy v Wyong Shire Council,[108] which took 12¾ years to resolve against the plaintiff in a four to three decision of the HCA; Mulligan v Coffs Harbour City Council;[109] and Roads and Traffic Authority of NSW v Dederer.[110] In this last case, a 14-year-old boy jumped from a bridge into water that was too shallow. The local council was held on appeal to the NSW Court of Appeal to be protected by the newly-enacted legislation.[111] The case went to the HCA against the road authority which had constructed and maintained the bridge and which, because the action had been commenced against it before the new legislation took effect, was not similarly protected. By a majority of three to two the HCA held that the authority had not been negligent and the plaintiff failed. Note that of the nine judges who heard the case at all three levels, five found for the plaintiff and four found for the defendant, but because three of those four were in the highest court the plaintiff was left uncompensated.

All these young men would have had cover in New Zealand under IPRCA. Mr Mulligan, who was a visitor from Ireland, might have received only limited benefits.[112] Indeed, the Woodhouse Report recommended that visitors be excluded,[113] but IPRCA s 23 excludes only persons not ordinarily resident who are injured aboard a ship or aircraft that brings them to or takes them from New Zealand or while embarking or disembarking on the ship or aircraft.

School liability

Children injured in playground accidents at school in Australia have to prove negligence if they are to recover any compensation. The difficulties they face are illustrated by Roman Catholic Church Trustees for the Diocese of Canberra and Goulburn v Hadba,[114] another decision showing how different judges come to different conclusions as to what amounts to reasonable care in the circumstances. The plaintiff, an eight-year-old child was injured when she fell to the ground after being pulled off a flying fox by a fellow student. The trial judge found that the school was not negligent in its supervision; this was reversed by a majority of the ACT Court of Appeal, which was in turn reversed by a majority of the HCA. Even the death of a school child from an accident during a sports class may be held to involve no breach of the duty of care.[115]

At the time of the Woodhouse report, there would have been little discussion of the topic of child sexual abuse, let alone contemplation of tort actions in respect of such events. New Zealand has not escaped the subsequent spate of litigation arising out of the revelation of the reality of abuse.[116] Victims of the sexual offences listed in Schedule 3 of IPRCA now have cover, including, exceptionally, for purely mental injuries not directly resulting from physical injuries.[117] The ACC statistics record these claims as “sensitive”.[118] Since the actual perpetrators are seldom able to pay damages, Australian courts, like others in the common law world,[119] have been faced, where the abuser was a school teacher, with claims against the school authorities. The HCA in New South Wales v Lepore[120], with one dissentient, rejected the view that a school authority could be liable for breach of a non-delegable duty of care where a pupil was sexually assaulted by a teacher. The majority judges were further divided between those who thought that there could never be vicarious liability for such an assault and those who contemplated that in some circumstances at least the actions of the teacher could be seen as an improper mode of performing an authorised activity.[121]

Vicarious liability

The uncertainty engendered by Lepore in relation to sexual assaults extends also to assaults by security guards (bouncers) at entertainment venues of various types. Numerous cases seeking to hold the employers liable have come before the Australian courts recently.[122] So far leave to appeal to the HCA in such cases has been refused on the grounds that the particular facts did not raise sufficient doubt.[123] However, it can be only a matter of time before such a case occupies our most eminent judicial minds.

Several other aspects of vicarious liability have, however, already come before the HCA in this century. Apart from Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd,[124] where the plaintiff was knocked down by a courier on a bicycle on the footpath and the court, by majority, held the courier company vicariously liable, all the plaintiffs who have sought to rely on vicarious liability in these cases have failed. In Scott v Davis[125] the owner of an aeroplane was held, by a majority, not liable for the pilot’s negligence in crashing the plane while giving the owner’s nephew a joy-ride at the owner’s request.[126] In Sweeney v Boylan Nominees Pty Ltd,[127] by majority, the court refused to extend the notion of non-delegable duties so as to make the defendant, who supplied and was under a duty to maintain a refrigerator in a shop, liable for the negligence of an independent contractor who serviced the refrigerator in such a way as to cause the door to fall on a customer. In Leichhardt Municipal Council v Montgomery,[128] the court refused to follow a line of English cases which had held that a road authority was liable for the negligence of independent contractors who repaired the road.

In none of these cases, if they had occurred in New Zealand, would the plaintiffs have needed, or been able, to explore the intricacies of the law of vicarious liability. They were all injured in what were clearly “accidents”; they would have been covered under IPRCA; they would have received their entitlements swiftly; and they would have been precluded from launching common law actions.

Problem areas

The Woodhouse report recognised that “[n]o system of compensation or damages is able to avoid all the ‘hard’ cases. In defining the area of protection the aim should be clarity and certainty and the avoidance of future dispute or disappointment”.[129] However, it recommended “the exclusion of incapacities arising from sickness or disease”,[130] other than those resulting from industrial diseases sustained by workers.[131] The report made the “further recommendation ... that a small group of medical and legal experts be appointed to study the question” of drawing the “line between injury by accident and sickness or disease”.[132] The subsequent failure to extend the scheme to all incapacities resulting from sickness or disease, means that the line remains obscure and common law actions may be available in areas that have presented difficulty for the Australian courts.[133] Some of these will now be indicated.

Mental injury

The IPRCA excludes mental injury not consequent on physical injury, except for mental injury consequent on the mostly sexual offences listed in Schedule 3: s 21. An amendment currently proposed by the Injury Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Compensation Amendment Bill (No 2) 2007 (NZ) cl 6, inserting a new s 21B, will extend cover to certain work-related mental injuries. Queenstown Lakes District Council v Palmer[134] opened the way for secondary victims of accidents who suffered only mental injury to sue at common law. Fairly restrictive limits on recovery in such circumstances were laid down in Van Soest v Residual Health Management Unit,[135] but Thomas J’s dissent gave an indication of how those limits might be swept aside. This is what happened in the HCA in Tame v New South Wales,[136] where although the plaintiff failed on the facts, the plaintiffs in the companion case of Annetts v Australian Stations Pty Ltd were successful. Once again the multiple judgments in these two cases led to some uncertainty, including a misinterpretation by the committee at the time reviewing the law of negligence for the Commonwealth and state governments, which claimed that the case established “that a duty of care to avoid mental harm will be owed to the plaintiff only if it was foreseeable that a person of ‘normal fortitude’ might suffer mental harm in the circumstances of the case if care was not taken”.[137] That this is not necessarily so became clear from the subsequent restatement of the new law by the members of the court in Gifford v Strang Patrick Stevedoring Pty Ltd.[138] Australian legislatures have regarded the removal by the HCA of legal impediments, as opposed to merely factual ones, as undesirable and have reintroduced restrictions to varying degrees.[139]

The HCA has itself shown its conservative side in relation to mental injury resulting from work stress in two cases, Koehler v Cerebos (Australia) Ltd[140] and, by a majority of four to three, in New South Wales v Fahy.[141] Since s 29(5)(a) of IPRCA excludes cover for workplace personal injury related to non-physical stress, a situation which would not be changed by the new provisions relating to mental injury in the current Bill, New Zealand workers may want to try to see whether they can do better than the unsuccessful plaintiffs in the two HCA cases.[142] Work stress claims were not stopped altogether in Australia by the first of those decisions.[143]

In one other case of alleged psychiatric injury after exposure to asbestos in the workplace the plaintiff was successful in the HCA, in the sense that he won, by a majority of three to two, a new trial on all issues after defeat at first instance: CSR Ltd v Della Maddalena.[144] This case again illustrates the vagaries of litigation, dependent on the individual judges who happen to be sitting, and the long drawn out nature of proceedings before any final resolution may be achieved.

Medical treatment

In 1963 Woodhouse J, as he then was, in Smith v Auckland Hospital Board[145] upheld a defendant’s motion objecting to the jury’s decision that a doctor had been negligent in failing to answer a patient’s question as to the risk of a procedure that the patient was to undergo. His decision was reversed by the Court of Appeal.[146] Nearly 30 years later, in Rogers v Whitaker[147] the HCA, without reference to this case, held that the single comprehensive duty of care of a medical practitioner in relation to examination, diagnosis and treatment includes an obligation to advise the patient of material risks. Failure to warn became a common allegation in numerous medical negligence cases.[148]

In Smith v Auckland Hospital Woodhouse J had relied on Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee,[149] which held that a doctor could not be negligent in following the practice of a responsible body of opinion within the profession. Rogers v Whitaker rejected this view with regard to the giving of advice. Later, in Naxakis v Western General Hospital,[150] the HCA similarly rejected the Bolam rule in relation to diagnosis and treatment. Afterwards, in Rosenberg v Percival[151] Gleeson CJ explained that in Rogers v Whitaker —

the relevance of professional practice and opinion was not denied; what was denied was its conclusiveness. In many cases, professional practice and opinion will be the primary, and in some cases it may be the only, basis upon which a court may reasonably act.[152]

The court in Rosenberg held that on the facts the WA Full Court should not have set aside the trial judge’s decision that the plaintiff would have gone ahead with the procedure even if warned of the risk which had not been disclosed.

Despite this reassuring turn, the medical profession became alarmed at the litigation to which it was exposed and lobbied for changes.[153] The lobbying bore some fruit, with (differing) legislation in the various jurisdictions making several changes, such as restoring the Bolam rule in a modified form, providing (probably unnecessary) protection for Good Samaritans who go to the assistance of injured people and introducing caps and thresholds on the recovery of damages.[154] More significantly, perhaps, in response to a crisis that beset the largest medical protection society in Australia owing to its failure to put aside sufficient reserves, the Commonwealth government introduced a series of ill-thought out measures to subsidise the medical indemnity insurance tort system.[155] The tort reforms may have stemmed the increase in claims, but did not stop it entirely. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission reported:

The ultimate number of claims increased by 91 per cent between 1997-98 and 2000-01 (from 1415 to 2707). The ultimate number of claims remained relatively constant over the next four years with 2487 claims in 2005-06.[156]

According to Insurance Statistics Australia Ltd, over the period from 1995/96 to 2005/06, using a rolling three-year average, claims against specialists practising plastic and cosmetic surgery, increased from 238 per 1000 practitioners to 335 (or 41%), while those against non-procedural general practitioners increased from 27 per 1000 to 37 (or 52%). For all the groups combined, the increase was from 45 per 1000 to 51 (or 13%).[157]

Probably owing to the paucity of such actions at the time of the Woodhouse report,[158] medical liability litigation was not singled out for attention in the report or the initial legislation.[159] It is pleasing to this observer that the subsequent introduction of a fault element in the coverage by the ACC of “medical misadventure” has now been eliminated with the recent amendment of IPRCA so as to cover “treatment injury”.[160] However, since “‘Treatment injury’ does not include ... (a) personal injury that is wholly or substantially caused by a person’s underlying health condition”,[161] there is still a need to distinguish between accident and sickness. The recent case of Accident Compensation Corporation v Ambros,[162] which arose under the former legislation, will not necessarily be easier to decide under the new. Furthermore, while “treatment” does include “(e) obtaining, or failing to obtain, a person’s consent to undergo treatment, including any information provided to the person ... to enable the person to make an informed decision on whether to accept treatment”,[163] what if a medical practitioner does not inform the patient of the fact that a painful form of treatment might not alleviate the underlying condition, the patient would not have undergone the treatment if he or she had been aware of this risk, and the underlying condition is not in fact improved? According to the Act, “[t]he fact that the treatment did not achieve a desired result does not, of itself, constitute ‘treatment injury’”.[164] May the patient then sue the doctor for negligence if a reasonable practitioner would have warned that there was a risk of not alleviating the underlying condition? Or if the medical practitioner does not inform the patient of “a necessary part, or ordinary consequence, of the treatment, taking into account all the circumstances of the treatment”, which is excluded from the definition of “treatment injury” by s 32(1)(c) and such “ordinary consequence” does occur? May the patient then sue at common law when a reasonable practitioner would have warned of this consequence?

Assume that a medical practitioner fails to inform a patient undergoing a sterilisation procedure that the procedure does not always achieve the desired result and a child is then born. Will New Zealand courts be faced with the issues that came before the HCA in cases that aroused an enormous amount of public controversy?[165] In Cattanach v Melchior[166] the HCA held, by a majority of four to three in judgments that extended to 414 paragraphs covering over 140 pages in the Commonwealth Law Reports, that the damages recoverable by the parents in such circumstances include the costs of raising the child, even if born healthy, and that there is to be no set off of benefits derived from the birth. Three states have passed legislation intended to reverse this decision,[167] but the other states and territories have chosen not to act. In the companion cases of Harriton v Stephens[168] and Waller v James; Waller v Hoolahan,[169] the HCA, with a lone dissenter, held that handicapped children either born or conceived, naturally or by IVF, as a result of negligent medical advice or diagnosis, could not themselves recover damages resulting from their birth. Such congenitally injured children would have been compensated under the broader Woodhouse proposals in Australia,[170] where it was provided that a physical or mental defect, including a disease, occurring or existing at or shortly after birth was to be treated as a personal injury. Since there is no similar provision in IPRCA, such a child would not have cover and could therefore sue, leading to the need for a court to consider whether the view of the majority or the dissent in the Australian cases is to be preferred.[171]

Products causing diseases to persons other than in the workplace

In Graham Barclay Oysters Pty Ltd v Ryan[172] a class action was brought on behalf of consumers who contracted hepatitis A from contaminated oysters grown in a lake in New South Wales, one of whom had died. The defendants were the growers and suppliers of the oysters, the local council in whose area the lake was, and the state of New South Wales. The trial judge held all three sets of defendants liable in negligence. He also held the growers liable under certain provisions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). On appeal to the full Federal Court, the council was exonerated from liability, but differing majorities upheld the other decisions. On further appeal to the HCA, the action against all three defendants in negligence failed, unanimously in respect of the council and the state, who were held not to owe a duty of care, and by four to three against the suppliers, who were held not to have breached their duty of care. The liability under the TPA was not in issue in the HCA, though there are some dicta suggesting that that should have failed too. Since an accident is defined in IPRCA s 25(1)(ba) as not including “the ingestion of a virus, bacterium, or protozoan, unless that ingestion is the result of the criminal act of a person other than the injured person”, the consumers of similarly contaminated oysters in New Zealand would not have cover and be able to sue. In such circumstances, the issues of duty of care and breach would need to be rehashed.

New Zealand has already had an unhappy experience with litigation against tobacco manufacturers in Pou v British American Tobacco (New Zealand) Ltd.[173] Class actions in Australia have failed to reach trial, the HCA having refused special leave to appeal against the repeated striking out of the plaintiffs’ pleadings.[174] One sole jury verdict in favour of a smoker after the defendants’ defence had been struck out because of the defendants’ destruction of documents did not survive an appeal or obtain special leave for a further appeal to the HCA.[175] It may be expected that more attempts will be made to sue tobacco companies. The “tort law reform” legislation in most jurisdictions exempts from its restrictive provisions claims “where the injury or death concerned resulted from smoking or other use of tobacco products”.[176]

Finally, one may point to the long, complex and mostly unsuccessful actions by people who have been exposed to asbestos outside the workplace. Very recently, several judgments at first instance in favour of home handymen who developed mesothelioma many years later were set aside on appeal to the intermediate appellate courts and the HCA refused leave to appeal.[177]

Conclusion

The personal injury negligence cases in Australia that have reached the HCA in this century and are discussed in this paper amply demonstrate that litigation is a lottery; that many injured people who embark on that litigation (let alone the multitudes who never obtain a chance to pursue claims) fail to achieve compensation; and that the road to determining who “wins” and who loses is long, arduous, slow and expensive. This paper has not dwelt on other flaws of the tort system, such as its adverse effects on rehabilitation, its failure to deter negligence or to promote safety and its inability to compensate long-term loss properly through an award of damages in a lump sum. All these matters were identified 40 years ago by the Woodhouse Royal Commission, which wisely recommended the abolition of the common law action for negligence causing personal injury. When its recommendations for replacement of the common law with an accident compensation scheme were implemented by means of a “social contract”,[178] New Zealand achieved the means of providing, as part of community responsibility, a speedy, effective and comparatively cheap remedy for all who were injured by accident. However, the boundary between injury by accident and sickness is sometimes blurred and the failure to extend the scheme to incapacity caused by illness threatens to provoke litigation with all its faults, thus putting at risk the benefits which the existing scheme provides.

[†] A slightly revised version of a paper delivered at a symposium “Accident Compensation: Forty Years on: A Celebration of the Woodhouse Report, Compensation for Personal Injury in New Zealand: Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry” at the University of Auckland on 13 December 2007.

[*] Professorial Fellow, Law School, The University of Melbourne. My thanks to Rosemary Tobin, Joanna Manning and Donal Nolan for their comments on my first draft.

[1] New Zealand, Royal Commission of Inquiry into Compensation for Personal Injury, Compensation for Personal Injury in New Zealand: Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry, R E Owen, Govt Printer, Wellington, 1967.

[2] For a recent re-articulation of these going beyond personal injury, see J Smillie, “The future of negligence” (2007) 15 TLJ 300.

[3] Summarised above n 1, para 171 (2): “erratic and capricious in operation”.

[4] Ibid, paras 71 and 79.

[5] Ibid, para 82 (“long delays inseparable from the very nature of the process”); paras 106-110, summarised in para 171 (4): “cumbersome and inefficient”.

[6] Ibid, paras 111-114, summarised in para 171(4): “extravagant in operation”.

[7] Ibid, para 170: “(always assuming that the defendant is insured or has means)”.

[8] Ibid, paras 123-125; summarised in para 171(1): “hinders the rehabilitation of injured persons”.

[9] Ibid, paras 115-122.

[10] Ibid, para 14.

[11] Ibid, para 290(a) and (b).

[12] Ibid, para 17.

[13] Australia, National Rehabilitation and Compensation Committee of Inquiry (Chairman, A O Woodhouse), Compensation and Rehabilitation in Australia: Report of the National Committee of Inquiry, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1974.

[14] M Priest, “A Man for Consensus but Not at All Costs”, Australian Financial Review, 3 March 2006.

[15] Eg, Harriton v Stephens [2006] HCA 15; (2006) 226 CLR 52 (wrongful life).

[16] Eg, occupiers’ liability cases such as Hoyts Pty Ltd v Burns [2003] HCA 61; (2003) 201 ALR 470 and Neindorf v Junkovic [2005] HCA 75; (2005) 222 ALR 631; or school liability cases such as Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Canberra and Goulburn (as St Anthony’s Primary School) v Hadba [2005] HCA 31; (2005) 221 CLR 161.

[17] Of the 79 personal injury cases that were decided by the HCA in 2000-07, 43 were road or industrial cases (some of the cases fell into more than one category).

[19] [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118.

[20] See A Crossland, “Negligence Review Fails to Cut The Cost of Proving Fault”, Australian Financial Review, Sydney, 4 October 2002.

[21] [2005] HCA 27; (2005) 215 ALR 418.

[22] [2004] HCA 64; (2004) 211 ALR 621.

[23] [2005] HCA 79; (2005) 223 ALR 228.

[24] [2003] HCA 34; (2003) 214 CLR 552. The NSW Court of Appeal had remarked in relation to the separate defence of illegality that “there is (unfortunately) no criminal offence involved in eating at McDonalds” (Berryman v Joslyn [2001] NSWCA 95; (2001) 33 MVR 441 at [22]).

[25] Berryman v Joslyn [2004] NSWCA 121 (23 April 2004, unreported, BC200402660).

[26] Berryman v Joslyn (no 2) [2004] NSWCA 239 (16 July 2004, unreported, BC200404578).

[27] [2002] NSWCA 205; (2002) 55 NSWLR 113.

[28] Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd [2004] HCA 29; (2004) 217 CLR 469.

[29] See G Orr and G Dale, “Impaired Judgements? Alcohol Server Liability and ‘Personal Responsibility’ after Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd” (2005) 13 TLJ 103.

[30] [2004] HCA 13; (2004) 205 ALR 56.

[31] Roads and Traffic Authority v Ryan [2005] NSWCA 34; (2005) 62 NSWLR 609.

[32] [2006] HCA 27; (2006) 226 CLR 256.

[33] Ibid, at [192].

[34] Osborne v Kelly (1993) 61 SASR 308 (FC).

[35] [1993] SASC 4357 (FC, King CJ, Bollen and Millhouse JJ, 23 December 1993, unreported); [1999] SASC 486 (FC, Doyle CJ, Mullighan and Wicks JJ, 12 November 1999, unreported).

[36] [2001] SASC 260 (Wicks J, 1 August 2001, unreported.)

[37] [1992] HCA 58; (1992) 175 CLR 479.

[38] See H Luntz, “Mrs Whitaker’s Gothic Cathedral” (1996) 4 TLJ 195. For further litigation and legislation arising out of this case, with more costs, see H Luntz, “Rogers v Whitaker: The Aftermath” (2003) 11 HLB 102.

[39] Ohlstein v E & T Lloyd trading as Otford Farm Trail Rides [2006] NSWCA 226; (2006) Aust Torts Reports 81-866 (NSW CA), SLG Lloyd v Ohlstein [2007] HCATrans 262 (25 May 2007); case settled on basis of judgment for defendants by consent: Lloyd v Ohlstein [2007] HCATrans 542 (13 September 2007); formal order Lloyd v Ohlstein [2007] HCATrans 621 (23 October 2007).

[40] Mr John Watkins, second reading speech on the Bill for the Motor Accidents (Lifetime Care and Support) Act 2006 (NSW), which came into force on 1 October 2006. See NSW Hansard, Legislative Assembly, 9 March 2006 <http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/PARLMENT/HansTrans.nsf/V3ByKey/LA20060309> (accessed 13 November 2007).

[41] See H Luntz, Assessment of Damages for Personal Injury and Death: General Principles, LexisNexis Butterworths, Sydney, 2006, Chap 2.

[42] See J Campbell, “Compo, Lump Sums and Structured Settlements” [2006] Accord 14

[43] Law Reform Commission (NSW), Accident Compensation: A Transport Accidents Scheme for New South Wales, Report No 43, NSWLRC, Sydney, 1984, <http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lrc.nsf/pages/R43TOC> (accessed 29 December 2004).

[44] Some of the recent cases in the Victorian Court of Appeal are Dodoro v Knighting [2004] VSCA 217; (2004) 10 VR 277 (CA); Hunter v Transport Accident Commission [2005] VSCA 1; (2005) 43 MVR 130 (Vic CA); Spence v Gomez [2006] VSCA 48; (2006) 45 MVR 556 (Vic CA); Arthur v Transport Accident Commission (Vic) [2006] VSCA 233; (2006) 47 MVR 182 (Vic CA)..

[45] (2000) 205 CLR 254. For criticism, see H Luntz, “Torts Turnaround Downunder” (2001) 1 OUCLJ 95; J Dietrich, “Liability in Negligence for Harm Resulting from Third Parties’ Criminal Acts: Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil” (2001) 9 TLJ 152.

[46] Trim Joint District School v Kelly [1914] AC 667.

[48] ACC Injury Statistics 2006 (First Edition), Section 13.2, Criminal Acts http://www.acc.co.nz/about-acc/acc-injury-statistics-2006/SS_WIM2_062850 (accessed 17 November 2007). As to “sensitive” claims, see below at nn 117 and 118.

[49] IPRCA s 317.

[50] [2001] HCA 6; (2001) 205 CLR 304.

[51] Ibid, at [64].

[53] Productivity Commission, National Workers’ Compensation and Occupational Health and Safety Frameworks, Report No 27, Canberra, 2004, <http://www.pc.gov.au/inquiry/workerscomp/docs/finalreport> (accessed 6 December 2007), Chap 8, pp 227 (citing D N Dewees, D Duff and M J Trebilcock, Exploring the Domain of Accident Law: Taking the Facts Seriously, Oxford University Press, New York; Oxford, 1996, p 355) and 296 (citing a working paper by Alan Clayton, 2002).

[54] Ibid, pp 235-6, 248 (“delays rehabilitation and return to work”). See also T G Ison, “Changes to the Accident Compensation System: An International Perspective” (1993) 23 VUWLR 25 at 34.

[55] Ibid, pp 297-8 (recommending that experience rating on the basis of no-fault benefits be confined to large employers). See also P S Atiyah, “Accident Prevention and Variable Premium Rates for Work-Connected Accidents--I and II” (1975) 4 Industrial LJ 1 and 89.

[56] See Productivity Commission, above n 53, Chap 10.

[57] See the sources cited in H Luntz and D Hambly, Torts: Cases and Commentary, revised 5th ed, LexisNexis Butterworths, Sydney, 2006, para [1.2.9].

[59] [2005] HCA 19; (2005) 221 CLR 234.

[60] Eg, TNT Australia Pty Ltd v Christie [2003] NSWCA 47; (2003) 65 NSWLR 1 (CA).

[62] The case is perceptively discussed by H Glasbeek, “The Legal Pulverisation of Social Issues: Andar Transport Pty Ltd v Brambles Ltd” (2005) 13 TLJ 217.

[63] See Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 44; (2001) 207 CLR 21 (plaintiff succeeded); Sweeney v Boylan Nominees Pty Ltd [2006] HCA 19; (2006) 226 CLR 161 (plaintiff failed), discussed below.

[64] So described by Meagher JA in New South Wales v Kennelly [2001] NSWCA 71 (10 April 2001, unreported, BC200101567).

[65] Eg, Clout Industrial Pty Ltd (in Liq) v Baiada Poultry Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 89; (2004) 61 NSWLR 111 (CA).

[66] Eg, Nominal Defendant v Hi-Light Industries Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 423; (2004) 61 NSWLR 585 (CA), SLR [2005] HCATrans 368 (27 May 2005).

[67] Recent ones are Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v GSF Australia Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 26; (2005) 221 CLR 568 and Nominal Defendant v GLG Australia Pty Ltd [2006] HCA 11; (2006) 225 ALR 643.

[68] See Transport Accident Act 1986 (Vic), s 94A; Accident Compensation Act 1985 (Vic), s 137A.

[69] Some recent illustrations are Pope v W S Walker & Sons Pty Ltd [2006] VSCA 227; (2006) 14 VR 435 (CA); Grech v Orica Australia Pty Ltd (2006) 14 VR 602 (CA); Mutual Cleaning and Maintenance Pty Ltd v Stamboulakis (2007) 15 VR 649 (CA); Kelso v Tatiara Meat Co Pty Ltd [2007] VSCA 267 (28 November 2007, unreported, BC200710238).

[70] [2002] UKHL 22; [2003] 1 AC 32.

[71] [2006] UKHL 20; [2006] 2 AC 572. The case has since been reversed on the proportionality point in relation to mesothelioma by the Compensation Act 2006 (UK) s 3.

[72] Eg, Wallaby Grip (BAE) Pty Ltd (in Liq) v Macleay Area Health Service (1998) 17 NSWCCR 355 (NSW CA), SLR sub nom Macleay-Hastings Area Health Service v Wallaby Grip (BAE) Pty Ltd (in liq) [1999] 19 Leg Rep SL 2 (19 November 1999); E M Baldwin & Son Pty Ltd v Plane [1999] Aust Torts Reps 81-499 (NSW CA), SLR [1999] 18 Leg Rep SL 4, sub nom Jsekarb Pty Ltd v Plane (8 October 1999).

[73] One contribution case did reach the HCA, only to be remitted to the lower courts for not having been dealt with properly: Amaca Pty Ltd v State of New South Wales [2003] HCA 44; (2003) 199 ALR 596. After that had been dealt with, another attempt to bring the case before the HCA was rejected: Amaca Pty Ltd v New South Wales [2004] NSWCA 124; (2004) Aust Torts Reports 81-749 (NSW CA), SLR [2005] HCATrans 93 (4 March 2005). An earlier contribution case in the HCA involving exposure to asbestos was James Hardie & Co Pty Ltd v Seltsam Pty Ltd (1998) 196 CLR 53.

[74] [2005] NSWCA 435; (2005) 65

NSWLR 187 (CA).

[75] See the

contribution proceedings in Amaca v CSR Ltd (re Eaton) [2006] NSWDDT 13; (2006) 3 DDCR

573.

[76] Crimmins v Stevedoring Industry Finance Committee [1999] HCA 59; (1999) 200 CLR 1. The Victorian Court of Appeal, to which the case was remitted, upheld the liability of the defendant authority on the facts: Stevedoring Industry Finance Committee v Henderson (for Estate of Crimmins) [2000] VSCA 216; (2000) 2 VR 396 (CA).

[77] James Hardie & Co Pty Ltd v Hall as administrator of estate of Putt (1998) 43 NSWLR 554 (CA), SLR S76/1998 (7 August 1998); James Hardie & Co Pty Ltd v Carley [1999] NSWCA 80 (23 March 1999, unreported, BC9901423); Amaca Pty Ltd v Frost [2006] NSWCA 173 (4 July 2006, unreported, BC200605025), SLR [2006] HCATrans 675 (8 December 2006). Cf James Hardie Industries Pty Ltd v Grigor (1998) 45 NSWLR 20 (CA), SLR [1998] Leg Rep SL 2 (7 August 1998).

[78] Union Shipping New Zealand Ltd v Morgan [2002] NSWCA 124; (2002) 54 NSWLR 690 (CA).

[79] Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd v Zaluzna (1987) 162 CLR 479.

[80] [2005] HCA 75; (2005) 222 ALR 631.

[81] [2003] HCA 61; (2003) 201 ALR 470.

[82] University of Wollongong v Mitchell [2003] NSWCA 94; (2003) Aust Torts Reports 81-708 (NSW CA), SLR [2004] HCATrans 181 (28 May 2004).

[84] [2002] NSWCA 205; (2002) 55 NSWLR 113.

[85] Cavalier v Pope [1906] UKHL 1; [1906] AC 428.

[86] See, eg, Occupiers’ Liability Act 1962 (NZ) s 8.

[87] Northern Sandblasting Pty Ltd v Harris (1997) 188 CLR 313. See G Orr, “The Glorious Uncertainty of the Common Law?: Northern Sandblasting Pty Ltd v Harris” (1997) 5 TLJ 208.

[88] Jones v Bartlett (2000) 205 CLR 166.

[89] [2001] HCA 29; (2001) 206 CLR 512.

[90] Ibid, at [163].

[91] See, eg, Boroondara City Council v Cattanach [2004] VSCA 139; (2004) 10 VR 109 (CA) (denying any higher standard of care towards the elderly, the frail, joggers, skateboarders, drunks, etc); Moyne Shire Council v Pearce [2004] VSCA 246; (2004) 136 LGERA 434 (Vic CA), SLR [2005] HCATrans 752 (9 September 2005).

[92] Eg, Whittlesea City Council v Merie [2005] VSCA 199 (11 August 2005, unreported, BC200505656), SLR [2005] HCATrans 1046 (16 December 2005); Temora Shire Council v Stein [2004] NSWCA 236; (2004) 134 LGERA 407 (NSW CA). See C Coventry, “You Had Better Watch Out: Liability of Public Authorities for Obvious Hazards in Footpaths” (2006) 14 TLJ 81; The Hon Justice D A Ipp AO, “The Metamorphosis of Slip and Fall” (2007) 29 Aust Bar Rev 150.

[93] The phrase comes from Littler v Liverpool Corporation [1968] 2 All ER 343 at 345 per Cumming-Bruce J , which was cited in, eg, Gondoline Pty Ltd v Hansford [2002] WASCA 214 (14 August 2002, unreported, BC200204570) at [58]; Burwood Council v Byrnes [2002] NSWCA 343 (4 November 2002, unreported, BC200206520) at [29].

[94] See, eg, Sutherland Shire Council v Pallister [2002] NSWCA 66 (19 March 2002, unreported, BC200201082); Richmond Valley Council v Standing [2002] NSWCA 359; (2002) Aust Torts Reports 81-679 (NSW CA); Burwood Council v Byrnes [2002] NSWCA 343 (4 November 2002, unreported, BC200206520), SLR [2003] HCATrans 462 (14 November 2003); Ryde City Council v Saleh [2004] NSWCA 219; (2004) Aust Torts Reports 81-757 (NSW CA).

[95] C Bradley and J E Harrison, Hospitalisations Due to Falls in Older People, Australia, 2003–04, AIHW cat. no. INJCAT 96, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, 2007, <http://www.nisu.flinders.edu.au/pubs/reports/2007/injcat96.php> (accessed 16 November 2007), pp 50-2.

[96] Ibid, Table 6.

[97] Hansford v Gondoline Pty Ltd [2003] HCATrans 429 (24 October 2003).

[98] Eg, Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) s 45. See also Coventry, above n 92.

[99] ACC Injury Statistics 2006 (First Edition), Section 20. Sport Claims <http://www.acc.co.nz/about-acc/acc-injury-statistics-2006/SS_WIM2_062694> (accessed 16 November 2007).

[100] [2000] HCA 41; (2000) 201 CLR 552.

[101] Eg, H Opie, “The Sport Administrator’s Charter: Agar v Hyde” (2001) 9 TLJ 131.

[102] Haylen v New South Wales Rugby Union Ltd [2002] NSWSC 114 (Einstein J, 15 March 2002, unreported, BC200200955); Green v Australian Rugby Football League Ltd [2003] NSWSC 749 (Harrison M, 14 August 2003, unreported, BC200304665).

[103] One of the cases mentioned in n 102 was proceeding in the NSW Supreme Court as this paper was being prepared: see G Jacobsen, “League advice not taken, court told”, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 November 2007, <http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/league-advice-not-taken-court-told/2007/11/05/1194117959756.html> (accessed 16 November 2007).

[105] Woods v Multi-Sport Holdings Pty Ltd (2002) 208 CLR 460. For a perceptive commentary on the masculine approach of the majority, see K Burns, “It’s Just Not Cricket: The High Court, Sport and Legislative Facts” (2002) 10 TLJ 234.

[106] The ACC statistics, n 99 above, do show that more than 100 New Zealanders also injure themselves each year while swimming, including at beaches and in rivers.

[107] B McDonald, “The Impact of the Civil Liability Legislation on Fundamental Policies and Principles of the Common Law” (2006) 14 TLJ 268 at 286; L Milligan, “Sandbar Victim Stripped of Payout”, The Australian, Sydney, 4 April 2003 (referring to the announcement after the NSW Court of Appeal reversed the decision).

[108] [2005] HCA 62; (2005) 223 CLR 422.

[109] [2005] HCA 63; (2005) 223 CLR 486. On this and the previous case, see N Foster, “Another Tale of Two Divers” (2006) 14 TLJ 115, referring to my earlier Editorial Comment, “A Tale of Two Divers” (1993) 1 TLJ 199.

[111] Great Lakes Shire Council v Dederer [2006] NSWCA 101; (2006) Aust Torts Reports 81-860 (NSW CA). On the complications stemming from the different forms that the protection might take in the different Australian jurisdictions, see J Dietrich, “Liability for Personal Injuries Arising from Recreational Services: The Interaction of Contract, Tort, State Legislation and the Trade Practices Act and the Resultant Mess” (2003) 11 TLJ 244.

[112] His entitlement to weekly and lump-sum compensation outside New Zealand would be subject to assessment by a person approved by the ACC and he would not be entitled to the costs of such assessment: s 127. Under s 128, unless there were regulations making such provision, the ACC could not pay for rehabilitation expenses once he had returned to Ireland, except for attendant care expenses under s 129, which could be limited to 28 days.

[114] [2005] HCA 31; (2005) 221 CLR 161.

[115] Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Archdiocese of Sydney v Kondrajian [2001] NSWCA 308 (24 September 2001, unreported, BC200105805), reversing the trial judge.

[116] See R Tobin, “Civil Actions for Sexual Abuse in New Zealand” (1997) 5 Tort L Rev 190; R Tobin, “Public Authorities and Negligent Investigations into Child Abuse: The New Zealand and English Approaches” (1999) 7 TLJ 232; J Manning, “The Reasonable Sexual Abuse Victim: ‘A Grotesque Invention of the Law’?” (2000) 8 TLJ 6; S Todd, “Tort Action by Victims of Sexual Abuse” (2004) 12 Tort L Rev 40.

[117] IPRCA s 21. Cf S v Attorney-General [2003] NZCA 149; [2003] 3 NZLR 450 (CA), where cover was held not to extend to events occurring before 1 April 1974 and the issue of vicarious liability on the part of foster parents had to be explored. Furthermore, as this case shows, even if there is cover under IPRCA, the possibility of exemplary damages under s 319 may require consideration of issues of vicarious liability.

[118] ACC Injury Statistics 2006 (First Edition), Section 13.1, Sensitive Claims <http://www.acc.co.nz/about-acc/acc-injury-statistics-2006/SS_WIM2_063154> (accessed 17 November 2007).

[119] Eg, Lister v Hesley Hall Ltd [2002] 1 AC 215 (HL).

[120] [2003] HCA 4; (2003) 212 CLR 511.

[121] As to the uncertainty thus created, see S v Attorney-General [2003] NZCA 149; [2003] 3 NZLR 450 (CA) at [63]; S White and G Orr, “Precarious Liability: The High Court in Lepore, Samin and Rich on School Responsibility for Assaults by Teachers” (2003) 11 TLJ 101; J Wangmann, “Liability for Institutional Child Sexual Assault: Where Does Lepore Leave Australia?” [2004] MelbULawRw 5; (2004) 28 MULR 169.

[122] Eg, Whitehouse Properties t/as Beach Road Hotel v McInerney [2005] NSWCA 436 (13 December 2005, unreported, BC200510724); Drinkwater v Howarth [2006] NSWCA 222 (3 August 2006, unreported, BC200606119); Ryan v Ann St Holdings Pty Ltd [2006] QCA 217 (16 June 2006, unreported, BC200604344); Sandstone Dmc Pty Ltd v Trajkovski [2006] NSWCA 205 (27 July 2006, unreported, BC200605689); Zorom Enterprises Pty Ltd v Zabow [2007] NSWCA 106 (4 May 2007, unreported, BC200703271); Sprod v Public Relations Oriented Security Pty Ltd [2007] NSWCA 319 (9 November 2007, unreported).

[123] See Riley v Francis [1999] NSWCA 52 (11 March 1999, unreported, BC9900825), SLR [2000] 7 Leg Rep SL 3 (17 March 2000); Starks v RSM Security Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 351; (2004) Aust Torts Reports 81-763 (NSW CA), SLR [2005] HCATrans 421 (17 June 2005).

[124] [2001] HCA 44; (2001) 207 CLR 21.

[126] See also Frost v Warner [2002] HCA 1; (2002) 209 CLR 509 (boating accident).