University of Melbourne Law School Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of Melbourne Law School Research Series |

|

DOES AN IMPROVED EXPERIENCE OF LAW SCHOOL PROTECT STUDENTS

AGAINST DEPRESSION, ANXIETY AND STRESS? AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF WELLBEING

AND THE

LAW SCHOOL EXPERIENCE OF LLB AND JD STUDENTS

WENDY LARCOMBE,* LETTY

TUMBAGA, IAN MALKIN, PIP NICHOLSON AND ORANIA TOKATLIDIS

ABSTRACT

Law students in Australia experience high rates of depression

and anxiety. This article reports findings from an empirical study investigating

the relation between law students’ levels of psychological distress and

their experiences of law school. The study was undertaken

at Melbourne Law

School and the sample included students from both the LLB and JD programs. While

Melbourne JD students expressed

a significantly higher level of satisfaction

with studying law, and their course experience, than Melbourne LLB students,

there were

no statistically significant differences in the levels of depression,

anxiety and stress reported by students in each cohort. This

finding suggests

that overall course satisfaction does not have a direct effect on

students’ levels of psychological distress.

More particularly, it

indicates that various program features that improve students’ experience

of law school do not automatically

result in improved levels of student

wellbeing. In this way, the study offers new insight into the relationship

between students’

experiences of law school and their levels of

psychological distress.

I INTRODUCTION

Law students in Australia experience disproportionately high rates of

depression and

anxiety.[1]

A 2008 survey of 741 law students in 13 Australian law schools found that one in

three respondents had high or very high levels of

psychological

distress.[2]

Yet law students are known to enter law school with rates of wellbeing no

different to, and even higher than, the general population:

apparently, legal

education at both graduate and undergraduate levels has a negative impact on

student wellbeing, and that impact

becomes evident within the first six to 12

months of the

degree.[3]

While recent research has found that university students generally are up to

four times more likely to be psychologically distressed

than other people their

age,[4] law students are known to

experience psychological distress at rates higher than students in comparable

professional degrees, including

medicine and

engineering.[5]

The documented

rates of psychological distress among law students make it imperative for law

schools to identify and modify the institutional

factors that trigger or

exacerbate student

ill-health.[6]

However, for interventions and reforms to be effective, they need to be based on

a sound understanding of the elements and features

of the ‘law school

experience’ that undermine, and those that support, students’

wellbeing. That understanding

is still emerging. Several broad theories have

been developed to date to account for the links between legal education and

students’

high rates of psychological distress. In particular, it is

postulated that wellbeing requires levels of social connectedness, autonomy,

self-esteem and a sense of

competence[7]

that are often undermined by the competitive and results-focussed culture that

prevails in many law schools.[8]

Additionally, some consider the process of learning to ‘think like a

lawyer’ to be inherently pessimistic and to distance

students from their

moral values and the social justice aspirations that often motivated their

decision to study

law.[9]

These theories provide important direction for law schools’ efforts to

address student mental health. However, they require

further refinement.

This article contributes to the evidence-base for effective law school

‘wellbeing’ approaches and strategies. It presents

selected findings

from a comprehensive empirical study of the relationship between law student

wellbeing and students’ experience

of law school. The study was undertaken

at Melbourne Law School (‘MLS’) in 2011, and the sample included

students from

both an LLB (undergraduate) program and a JD (graduate-entry)

program. Overall, Melbourne JD students expressed a significantly higher

level

of satisfaction with studying law, and with their course experience, than

Melbourne LLB students. As discussed below, this

may be attributable in part to

the selection of a graduate cohort based on interest and aptitude for study in

law, as well as prior

academic achievement. It may also be attributable to the

differences between studying law in a ‘combined degree’ course

and

studying law full-time.[10] Given

the differences in law school experience, however, the study findings regarding

students’ psychological health were somewhat

surprising: there were no

statistically significant differences in the levels of depression, anxiety and

stress reported by students

in the Melbourne JD program when compared with

students in the Melbourne LLB program. This finding suggests that overall course

satisfaction

does not have a direct effect on students’ levels of

psychological distress. More particularly, it indicates that various program

features that improve students’ experience of law school do not

automatically result in improved levels of student wellbeing.

In this way, the

study offers new insight into the relationship between students’

experiences of law school and their levels

of psychological

distress.

Part II of the article outlines the aims and methods of the

research undertaken into student wellbeing at MLS in 2011. Part III presents

selected results on student wellbeing and the law school experience. Part IV

discusses these results in the context of respondents’

suggestions for

improving wellbeing. Part V reflects on the study’s findings in relation

to the published literature on law

student wellbeing.

II AIMS AND METHODS OF THE STUDY

An empirical study of law student wellbeing at MLS was initiated by the

authors in 2010[11] in response to

the growing body of evidence, noted above, about psychological distress among

law students in Australia, and also

anecdotal evidence of significant levels of

distress among students at MLS.[12]

The project was designed to collect empirical data that would provide an

evidence-base for development of a school-wide student wellbeing

plan.[13] Consequently, the project

undertook to document the levels of depression, anxiety, stress and wellbeing

experienced by MLS students

in both the LLB and JD programs. It was anticipated

that demographic and course information, correlated with wellbeing levels, would

enable us to identify student groups or aspects of the programs that needed

particular attention. The wellbeing data would then provide

a

‘baseline’ against which the effectiveness of future interventions

could be assessed.

The study also collected data about students’

experience of law school, the sources of stress that they perceived affected

them,

and their suggestions for strategies that the law school could adopt or

extend in order to improve and support student wellbeing.

The decision to focus

on students’ experience of law school was made because current research

findings establish a strong connection

between the experience of studying law

and high rates of psychological distress. As researchers, we were thus

interested in attempting

to illuminate the aspects of law school that trigger or

exacerbate student distress. More particularly, we sought to identify the

causes

of distress that are within the power of law schools to change. A range of

external factors no doubt contribute to law students’

levels of stress,

anxiety and depression, including the increasing costs of legal education, the

shrinking job market, and the increased

competition for the limited number of

jobs as more and more law courses add thousands of new law graduates to local

and national

markets each year.[14]

While law schools need to be aware of and prepare students to negotiate these

realities, they are not within the power of law schools

to change. Our

particular interest, however, was in further investigating and developing

understanding of the changes or interventions

law schools can make in

order to improve student wellbeing.

In that vein, other studies have

concentrated on the ‘analytical-adversarial’ cognitive paradigm

taught and modelled in

law schools — ‘learning to think like a

lawyer’ — and its contribution to law students’ psychological

distress.[15] One such study,

conducted at the Australian National University (‘ANU’), found a

correlation between first year law students’

lower use of experiential

modes of thinking and increases in their levels of psychological

distress.[16] This is an important

finding. However, it is not yet established whether it is thinking like a lawyer

alone that can be harmful to

psychological health, or only when combined with

attendance at law school. The analytical-rational thinking style typical of

‘thinking

like a lawyer’ is always ‘learned’ (and

valued) within a broader context: law school.

To contribute to understanding

of the impact on psychological health of the broader law school experience, our

research focus was

on the features and elements of law school life in addition

to legal reasoning that the literature suggests might impact adversely

on

students’ psychological health — for example, students’

interest in and aptitude for study in law, as well as

their degree of

satisfaction with the course; their level of social involvement with peers and

engagement in law school activities;

their experiences of academic difficulties

and perceptions of academic support. In this way, we sought to investigate the

research

question: Is there a relationship between students’ experience of

law school and their psychological health?

This question was investigated

in relation to two distinct cohorts of law students. Having become an entirely

graduate-entry law school

in

2008,[17]

by 2011, MLS had substantial enrolments in both the final years of its

undergraduate LLB program and all years of its graduate-entry

JD program (see

Table 1 below).[18] Moreover,

the two programs had significantly different features. For example, the LLB was

typically studied as part of a five-year

‘combined course’ program

in which students took only one or two compulsory law

subjects[19] each semester of the

first three years and then a full enrolment of law subjects in the final two

years of the program. As a result,

student engagement with the law school, and

even identification as a law student, could be limited in the early years by the

demands

of their complementary course. Moreover, the intake into the LLB was

around 430 students per year — predominantly high achieving

school

leavers, some of whom were studying law because they achieved the marks required

for entry or as a result of parental advice

rather than as a result of their

interest in and perceived aptitude for

law.[20] Interactions between

students and lecturers, in and out of class time, were limited: while first

year, first semester LLB subjects

were taught in seminar groups of 45-60, later

year compulsory subjects generally involved class sizes above 60.

By

contrast, the Melbourne JD is a

full-time,[21] 3-year graduate-entry

law degree. Students are expected to attend all classes — which are taught

in seminar-style — and

the maximum class size is 60. A two-week

foundational course in Legal Method and Reasoning, taught in groups of 25 prior

to the start

of first semester, enables commencing students to build strong

social connections within their cohort and also with the first year

teachers.[22] Students are selected

into the JD on the basis of interest and aptitude for study in law, as

demonstrated by academic results in

their first degree, scores on the LSAT test,

and a personal statement. The intake into the program during the period of the

study

(2009–2011) grew from 120 to 240 but did not approach the LLB intake

numbers. The full-time nature of the degree enables students

not only to form

strong relationships with their peers but also to make conceptual connections

across the curriculum so that they

develop a more holistic and integrated

understanding of law.[23] The

full-time nature of the degree has also enabled a range of measures to be

intentionally instituted within the design of the MLS

JD program to promote

academic engagement, social connections, timely access to academic support and

wellbeing

awareness.[24]

As

a result of these differences between the two programs, we hypothesised that JD

students would have a different ‘experience’

of law school when

compared with LLB students. Further, we hypothesised that the likely differences

in law school experience would

have a bearing on students’ levels of

psychological wellbeing.

A Methods and Measures

The study collected data about law student wellbeing and the law school

experience using a specially developed online survey and focus

group

discussions.[25] An online survey

was considered the best means of encouraging student participation in the

project as it would ensure anonymity and

voluntary participation. The survey

items were developed based on a literature review and interviews with

stakeholders including

the Law Student Welfare and Wellbeing Coordinator at MLS,

the Academic Skills advisors, Careers Advisers, and representatives from

the law

student societies. In summary, the Wellbeing Survey collected information about

students’ levels of wellbeing and distress;

perceived sources of stress;

the law school experience; help-seeking behaviour and coping strategies; and

suggestions for improving

student wellbeing.

Two measures of

psychological wellbeing were used: the DASS-21 to measure negative mental health

and Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing

Scales to measure positive mental

health. The DASS-21 (or Depression, Anxiety, Stress

Scale-21)[26] is a 21 item,

self-report measure comprising 3 subscales with 7 items each for depression,

anxiety and stress. It was selected over

other depression scales (for example,

the Kessler Psychological Distress

Scale)[27] to measure levels of

psychological distress among Melbourne law students because of its brevity, its

high reliability and the availability

of strong Australian normative DASS data

for comparison, as set out below. The Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing

Scales were included

to measure six distinct elements of positive functioning

that encompass

wellness,[28]

namely:

The decision to use the Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing Scales

was informed by previous studies of law student psychological

distress which

indicate that wellbeing requires regular experiences of social connectedness,

autonomy, self-esteem and a sense of

competence.[29] These experiences

are generally considered to be protective against depression, anxiety and stress

and Ryff’s is a well-established

and widely used scale that measures these

wellbeing factors.[30]

In

addition to the wellbeing measures, a number of survey items were developed to

identify possible triggers of psychological distress

and awareness of support

services. Twenty-five items explored students’ experience of law school.

Survey participants were

prompted to provide suggestions for improving student

wellbeing at MLS by rating a list of provided suggestions as well as through

provision of an open-ended textbox. Respondents could skip any question in the

survey that they did not want to answer. This option

was provided to ensure that

students felt ‘safe’ that they could not be identified from their

responses, and that they

were not likely to be distressed by completing the

survey. Ethics approval for the data collection was sought and obtained from the

University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics

Committee.[31] The finalised survey

was administered from 2–21 August 2011.

Four focus group

discussions (‘FGDs’) were organised to supplement the quantitative

and qualitative data collected through

the surveys. Participants were recruited

through the online survey, independent advertising and emails to all students

and staff.

The FGDs were facilitated by facilitators who were independent of MLS

but familiar with the Wellbeing Survey results. A total of

17 students and staff

participated in the FGDs (2 males, 15 females; 2 LLB students, 9 JD students, 6

staff members). Six of the

student participants were representatives from the

student societies. All participating staff members were non-academic

staff.

B Profile of the Survey Respondent Sample

A total of 327 respondents, or 37 per cent of all eligible MLS students,

participated in the online survey (see Table 1), although not all

respondents completed all questions. Seventy four per cent of respondents were

in the JD program and 26 per cent

in the LLB, meaning that JD students were

over-represented in the respondent sample. Almost all of the LLB students were

in their

5th year of the program.

Table 1. MLS survey sample and MLS student population (August 2011)

|

2011 Second Semester MLS Enrolment

|

MLS SURVEY SAMPLE SIZE

|

||||

|

Course and

ECD year |

Description

|

Count

|

Course and Year level

|

# of

Respondents |

% of Student Population

|

|

JD, 2011

|

Final year JD

|

71

|

JD 3rd year

|

29

|

41%

|

|

JD, 2012

|

Second year JD

|

156

|

JD2nd year

|

79

|

51%

|

|

JD, 2013

|

First year JD

|

225

|

JD first year

|

99

|

44%

|

|

JD, 2014

|

First year JD (reduced load)

|

14

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total JD

|

207

|

44%

|

|

LLB, 2011

|

Final year LLB

|

270

|

|

|

|

|

LLB, 2012

|

Penultimate LLB

|

133

|

|

|

|

|

LLB, 2013

|

Other LLB

|

11

|

Total LLB

|

75

|

18%

|

|

|

|

|

Missing data

|

43

|

|

|

|

Total Enrolment

|

880

|

Total sample

|

327

|

37 % of total 880

|

Respondents were asked to provide information about their gender, age,

residency, study load and fee-type to enable us to compare

the respondent sample

with our student population. Given that female students comprise approximately

55 per cent of the JD intake,

they were slightly over-represented in the survey

sample: 68 per cent of respondents identified as female, 31 per cent as male,

and

1 per cent as other. The mean age of participants was 24 years, with a range

of 20 to 49 years.

III SURVEY FINDINGS

A Levels of Psychological Distress and Wellbeing

As outlined above, respondents were asked to complete the DASS-21 to provide

a measure of their negative psychological health. The DASS-21 has 3

subscales with 7-items each for depression, anxiety and stress. The DASS

depression subscale measures hopelessness, low self-esteem and low

positive affect. The DASS anxiety subscale measures autonomic arousal,

physiological hyper-arousal and the subjective feeling of fear. The DASS

stress subscale measures tension, agitation and negative

affect.[32] Respondents were asked

to reflect on the past week and rate statements on a 4-point scale, ranging from

‘did not apply to me

at all’ (0) to ‘applied to me very much

or most of the time’ (3). Based on their responses, respondents are given

a clinical score on each subscale, which determines classification within five

levels of depression, anxiety and/or stress, namely:

‘normal’,

‘mild’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’, or

‘extremely severe’.

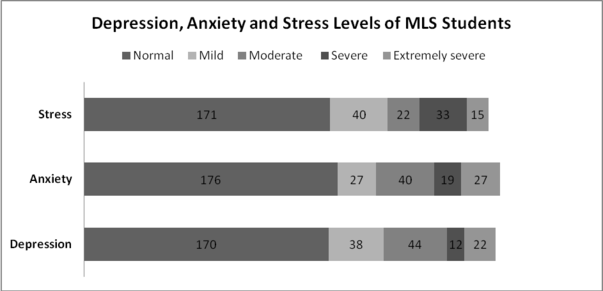

Figure A shows that while

approximately half of the respondents were in the normal range for stress,

anxiety and depression, half of MLS respondents

were experiencing levels of

depression, anxiety and stress beyond the normal ranges.

Figure A. Distess levels of MLS students (August 2011)

Table 2 presents the information as percentages within each of the

DASS levels. As it shows, close to 30 per cent of MLS students were experiencing

moderate to extremely severe levels of depression or anxiety. At these levels,

students’ daily functioning — for example,

their ability to

concentrate, and to remember and process information — is likely to be

adversely affected. Students experiencing

severe and extremely severe levels of

stress, anxiety or depression are likely to need professional assistance to

address their psychological

distress.

Table 2. Depression, anxiety and stress levels of MLS Students (in percentages)

|

Level

|

Depression

N |

Valid %

|

Anxiety

N |

Valid %

|

Stress

N |

Valid %

|

|

Normal

|

170

|

59.4%

|

176

|

60.9%

|

171

|

60.9%

|

|

Mild

|

38

|

13.3%

|

27

|

9.3%

|

40

|

14.2%

|

|

Moderate

|

44

|

15.4%

|

40

|

13.8%

|

22

|

7.8%

|

|

Severe

|

12

|

4.2%

|

19

|

6.6%

|

33

|

11.7%

|

|

Extremely severe

|

22

|

7.7%

|

27

|

9.3%

|

15

|

5.3%

|

When data was cross-tabulated across the three subscales, it was observed

that some respondents who rated in the normal range on the

depression subscale

were mildly, moderately or even severely anxious or stressed. Only 45 per cent

of respondents were in the normal

range across all three subscales of

depression, anxiety and stress.

These rates of psychological distress

amongst MLS students are similar to other national data on law student mental

health. Recent

research undertaken at the ANU College of Law with first year LLB

students also used the DASS-21 and found that 30 per cent of first

year students

were moderately to extremely severely depressed and/or anxious by the end of

their first year.[33] Table 3

compares the results of the ANU and MLS studies in terms of the percentage

of respondents within the various DASS levels.

Table 3. Depression, anxiety and stress levels of MLS and ANU students (in percentages)

|

|

DEPRESSION %

|

ANXIETY %

|

STRESS %

|

|||

|

|

MLS

|

ANU

|

MLS

|

ANU

|

MLS

|

ANU

|

|

Normal

|

59.4

|

54.9

|

60.9

|

61.5

|

60.9

|

67.1

|

|

Mild

|

13.3

|

13.6

|

9.3

|

8.0

|

14.2

|

12.7

|

|

Moderate

|

15.4

|

18.8

|

13.8

|

14.6

|

7.8

|

9.4

|

|

Severe

|

4.2

|

4.7

|

6.6

|

5.2

|

11.7

|

7.0

|

|

Extremely severe

|

7.7

|

8.0

|

9.3

|

10.8

|

5.3

|

3.8

|

|

Moderate and above

|

27.3

|

31.5

|

29.7

|

30.6

|

24.8

|

20.2

|

From the data it can be seen that both MLS and ANU data are broadly

consistent with the results of a national study into mental health

among the

legal profession and law students which, although it used a different measure,

similarly found that 35 per cent of law

students reported high or very high

levels of psychological

distress.[34]

Student

distress is an insufficient measure of student mental health as it focuses only

on negative clinical symptoms, and overlooks

the fact that positive experiences

are required for overall wellbeing. To gather a more balanced perspective of

student wellbeing,

we administered the Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing

Scale to measure positive psychological health in relation to the six dimensions

outlined above: Personal Growth; Environmental Mastery; Positive Relationships

With Others; Self-acceptance; Purpose in Life; and

sense of Autonomy. Previous

studies undertaken by the scale developers have shown that multiple indicators

of depression are consistently

associated negatively with all of Ryff’s

dimensions of wellbeing, with the strongest negative correlations between

depression

and Self-acceptance as well as depression and Environmental

Mastery.[35]

Our survey

results on the Ryff’s Wellbeing scale (Table 4) indicate that MLS

students have high levels of Personal Growth and sense of Purpose while Positive

Relationships With Others was

neither high nor low. Scores were below the total

wellbeing mean score, however, for Environmental Mastery, sense of Autonomy and

Self-acceptance, indicating that these are the three areas where student

wellbeing may be undermined currently by law school

practices.[36]

Table 4. MLS Students’ mean scores on Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing Scales

|

Psychological Wellbeing (Ryff’s)

|

N

|

Mean*

|

Std. Dev

|

|

|

Personal Growth

|

291

|

6.12

|

0.67

|

High

|

|

Environmental Mastery

|

293

|

4.60

|

1.24

|

Low

|

|

Positive Relationships With Others

|

291

|

5.38

|

1.14

|

Neutral

|

|

Self-acceptance

|

292

|

5.00

|

1.25

|

Low

|

|

Purpose

|

289

|

5.59

|

0.92

|

High

|

|

Autonomy

|

292

|

4.87

|

1.14

|

Low

|

|

Total wellbeing

|

284

|

5.26

|

0.74

|

|

*Note: On a 7-point scale

Low scores on these wellbeing

dimensions can also provide some explanation for high levels of depression in

our respondent population.

Based on correlation studies of the DASS and

Ryff’s scale scores, we found a statistically significant negative

correlation

between student depression, anxiety and stress and Environmental

Mastery, Self-acceptance and Positive Relationships With Others

(see Table

5). In other words, as depression or anxiety or stress increased,

Environmental Mastery, Self-acceptance, Positive Relationships With

Others and,

to some extent, Autonomy decreased. The inverse also applied: as Environmental

Mastery, Self-acceptance and Positive

Relationships increased, depression,

anxiety and stress decreased. Autonomy was significantly negatively correlated

with anxiety

and stress, but not with depression. Interestingly, anxiety and

stress were not affected by Personal Growth and sense of Purpose,

as previous

studies would indicate.[37] So,

while most respondents registered a high sense of Personal Growth and sense of

Purpose, these factors did not protect law students against anxiety or

stress. However, a negative correlation was found between depression and

Personal Growth

and Purpose.

Table 5. Correlation table: DASS-21 Scales and Ryff’s Wellbeing Scale

|

|

Anxiety

|

Depression

|

Personal

Growth

|

Environment Mastery

|

Positive Relations with Others

|

Self-acceptance

|

Purpose

|

Autonomy

|

|

DASS Stress

|

.728**

|

.630**

|

0.077

|

-.515**

|

-.347**

|

-.383**

|

0.038

|

-.232**

|

|

DASS Anxiety

|

|

.562**

|

-0.075

|

-.510**

|

-.350**

|

-.358**

|

-0.074

|

-.227**

|

|

DASS Depression

|

|

|

-0.230**

|

-.662**

|

-.417**

|

-.524**

|

-.293**

|

-0.130

|

|

Ryf Pers Growth

|

|

|

|

.260**

|

.189**

|

.283**

|

.345**

|

.158*

|

|

Ryf Environ Mastery

|

|

|

|

|

.373**

|

.629**

|

.239**

|

.273**

|

|

Ryf Positive Rel

|

|

|

|

|

|

.494**

|

.193**

|

0.066

|

|

Ryf Self Accept

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.281**

|

.339**

|

|

Ryf Purpose

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.105

|

|

Ryf Autonomy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Overall, these

findings indicate that law students’ mental health would be improved if

measures were introduced to increase

students’ perceptions of

Environmental Mastery, Self-acceptance and Positive Relations With

Others.

B Law School Experience

The twenty-five survey items that sought information on students’ experiences of studying law and being a law student all asked students to rate their level of agreement with a statement using a 5-point scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. The results of a factor analysis showed that these items loaded onto six themes, which we labelled as:

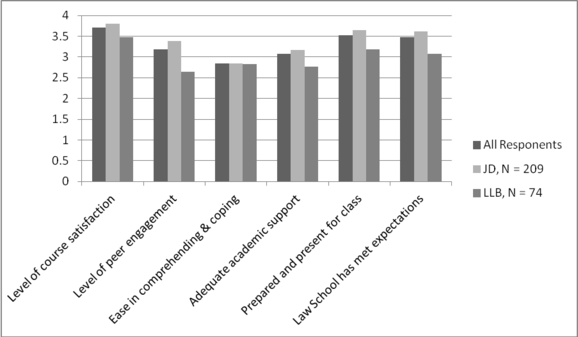

Means on the six law school experience

(‘LSE’) scales show that respondents were generally satisfied with

their course

(mean 3.71) and felt that law school had met their expectations

(mean 3.48). A significant proportion had experienced difficulty

comprehending

the course material or coping with the workload (ease of comprehending and

coping mean 2.84). Levels of peer engagement

were not high (mean 3.19), although

a majority indicated that they generally prepared for and were present at their

classes (mean

3.52) which may be considered as a measure of academic engagement.

Perceptions of the level of academic support provided by lecturers

were not

positive (mean 3.07). To gain further insight into students’ experience of

law school, and its implications for wellbeing,

we investigated differences in

LSE by program.

Figure B: Means (5-point scale) on law

school experience factors

As Figure B shows, there were significant differences between the reported experiences of LLB students and JD students within the respondent sample. Overall, JD students reported a significantly better experience of law school when compared with LLB students. On the six identified themes, t-tests showed that differences between mean responses from JD and LLB students were significant (at p<.05) on all but Comprehending and Coping (Figure B). Table 6 provides further detail on the differences in LSE of LLB and JD students. In this table, Strongly Agree and Agree responses have been collapsed into a single ‘Agree’ category and Strongly Disagree and Disagree responses have been collapsed into a single ‘Disagree’ category.

Table 6. Law School Experience, LLB and JD (percentage agreement)

|

Law School Experience

JD, LLB comparison (JD, n=210; LLB, n=75) Negative items are indicated as: (-) |

JD Disagree %

|

LLB Disagree %

|

JD Neither agree nor disagree %

|

LLB Neither agree nor disagree %

|

JD Agree %

|

LLB Agree %

|

Rating Average JD

|

Rating Average LLB

|

|

COURSE SATISFACTION THEME

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overall I am enjoying my law studies.

|

12

|

14

|

10

|

23

|

78

|

64

|

3.82

|

3.53

|

|

I really like being a Law student.

|

10

|

15

|

20

|

36

|

70

|

50

|

3.79

|

3.39

|

|

So far I have found most of my subjects to be interesting.

|

11

|

10

|

13

|

13

|

77

|

77

|

3.84

|

3.77

|

|

I derive satisfaction from studying law.

|

5

|

11

|

14

|

28

|

80

|

61

|

3.98

|

3.55

|

|

I think that the subjects I am studying fit well together.

|

8

|

7

|

23

|

36

|

69

|

58

|

3.67

|

3.51

|

|

I can see the connection between my subjects and future career

prospects.

|

12

|

29

|

19

|

20

|

69

|

51

|

3.67

|

3.16

|

|

I am clear about my reasons for studying law.

|

12

|

28

|

17

|

27

|

70

|

45

|

3.77

|

3.21

|

|

Studying law will really help me get what I want in life.

|

4

|

11

|

20

|

40

|

76

|

50

|

3.89

|

3.45

|

|

PEER ENGAGEMENT THEME

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I actively participate in many of the school activities.

|

37

|

59

|

20

|

12

|

44

|

29

|

3.10

|

2.64

|

|

I feel that the Law School encourages students to form healthy and

supportive relationships with each other and other members of the

law school

community.

|

26

|

58

|

27

|

24

|

47

|

17

|

3.19

|

2.46

|

|

I regularly study with other law students.

|

45

|

74

|

17

|

9

|

39

|

17

|

2.90

|

2.13

|

|

Studying with a small group of students in LMR was important for making

social connections with peers in the degree.

|

8

|

31

|

13

|

37

|

79

|

32

|

4.06

|

2.85

|

|

Working closely with others in my cohort is a positive aspect of my Law

School experience.

|

18

|

33

|

14

|

29

|

67

|

37

|

3.67

|

2.96

|

|

COMPREHENDING AND COPING THEME

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I feel overwhelmed by everything I have to do. (-)

|

24

|

28

|

14

|

20

|

61

|

52

|

3.48

|

3.35

|

|

I have had difficulty adjusting to the style of teaching at the Law School.

(-)

|

45

|

39

|

21

|

27

|

34

|

34

|

2.86

|

3.03

|

|

I find it really hard to keep up with the volume of work in my program.

(-)

|

12

|

20

|

24

|

21

|

64

|

58

|

3.68

|

3.53

|

|

I find it difficult to comprehend a lot of the material in my Law

subjects.(-)

|

53

|

46

|

24

|

23

|

23

|

31

|

2.67

|

2.81

|

|

ACADEMIC SUPPORT THEME

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I think that teachers at the Law School make a real effort to understand

the difficulties that students may be having.

|

20

|

34

|

37

|

33

|

43

|

33

|

3.24

|

2.95

|

|

I find that teachers at the Law School do not give as much feedback to

students as they should. (-)

|

25

|

12

|

20

|

24

|

56

|

64

|

3.43

|

3.72

|

|

My transition to first year study in Law was helped by the foundational

course, LMR.

|

18

|

25

|

11

|

27

|

70

|

47

|

3.71

|

3.09

|

|

PREPARED AND PRESENT THEME

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I regularly come to class without completing readings or assigned work.

(-)

|

54

|

19

|

17

|

15

|

29

|

67

|

2.68

|

3.64

|

|

I find it difficult to motivate myself to study. (-)

|

35

|

28

|

24

|

16

|

41

|

56

|

3.07

|

3.39

|

|

It's important to me to attend all my classes.

|

3

|

18

|

10

|

12

|

87

|

71

|

4.24

|

3.75

|

|

I am fully responsible for my own learning and academic performance.

|

9

|

9

|

7

|

11

|

84

|

80

|

4.03

|

3.97

|

|

EXPECTATIONS ITEM

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Law school hasn’t lived up to my expectations.(-)

|

65

|

36

|

20

|

37

|

14

|

27

|

2.38

|

2.95

|

It is evident that JD students enjoy higher Course Satisfaction than LLB

students. Most notably, 80 per cent of JD students derive

satisfaction from

studying law compared with 61 per cent of the LLB students. Further, while 70

per cent of JD students are ‘clear

about their reasons for studying

law’, only 45 per cent of the LLB students are. Only 50 per cent of the

LLB students agreed

that ‘studying law will really help me get what I want

in life’ and 29 per cent could not see ‘the connection between

my

subjects and future career prospects’. In contrast, 76 per cent of JD

students agreed that ‘studying law will really

help me get what I want in

life’ and only 12 per cent could not see ‘the connection between my

subjects and future career

prospects’.

Differences in levels of

Peer Engagement between the LLB and JD students are also evident. Although the

majority of students in both

programs indicated that they were not highly

engaged with their peers, JD students were more likely to be engaged with peers

than

LLBs. For example, 74 per cent of LLB students said that they did not

‘regularly study with other law students’ (compared

with 45 per cent

JDs) and 59 per cent did not ‘actively participate in many of the school

activities’ (compared with

37 per cent JDs). Two-thirds (67 per cent) of

the JD students felt that ‘working closely with others in my cohort is a

positive

aspect of my Law School experience’, compared with only one-third

(37 per cent) of the LLB students. It must be noted that

the majority of

students in both programs felt that the law school did not encourage students to

form healthy and supportive relationships

with each other and other members of

the law school community. The differences between programs are significant here,

however: 47

per cent of JD students felt the law school encouraged healthy

relationships compared to only 17 per cent of LLB students.

In relation

to Academic Support, a majority of students in both programs did not feel that

teachers ‘make a real effort to understand

the difficulties that students

may be having’, although JD students were more likely than LLB students to

feel that they did

(43 per cent JD, 33 per cent LLB). Similarly, most students

in both programs felt that teachers ‘do not give as much feedback

to

students as they should’ (56 per cent JD, 64 per cent LLB), although more

JD students were satisfied with the level of feedback

received (25 per cent)

than LLB students (12 per cent). One third of the students in each program (34

per cent JD, 34 per cent LLB)

had ‘had difficulty adjusting to the style

of teaching at the Law School’.

Finally, law school has

‘lived up to the expectations’ of almost two-thirds (65 per cent) of

the JD students but only

one-third (36 per cent) of the LLB students. This

confirms that, overall, many more JD students than LLB students were having a

positive

experience of law school and finding that law school met their

expectations. The next question was to determine whether this difference

in law

school experience had an impact on students’ psychological health.

C Law School Experience and Students’ Psychological Health

Analysis of variance (‘ANOVA’) and t-tests were run to test

whether there were significant differences in levels of depression,

anxiety,

stress and/or wellbeing between the two programs and across different student

groups.

By program, although DASS mean scores varied between LLB

and JD students, t-tests revealed that differences in the mean scores were not

statistically

significant (at p<.05 level) (see Table

7).

Table 7. DASS-21 scores by program, descriptive statistics and non-significant t-test results

|

Program

|

N

|

Mean

|

sd

|

t |

sig

|

|

Stress

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LLB

|

68

|

14.41

|

9.80

|

|

|

|

JD

|

206

|

14.30

|

9.40

|

0.08

|

0.93

|

|

Anxiety

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LLB

|

74

|

6.95

|

7.96

|

|

|

|

JD

|

208

|

7.57

|

7.78

|

-0.58

|

0.56

|

|

Depression

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LLB

|

73

|

10.33

|

9.91

|

|

|

|

JD

|

206

|

9.19

|

9.11

|

0.86

|

0.39

|

There were also no differences in DASS levels between the year levels within the programs: while the mean scores showed that first year JD students had lower levels of stress, anxiety and depression compared to 2nd and 3rd year JD students and all LLB students, this difference was not statistically significant (at p<.05 level). This means that, if the first year JD students’ psychological health was in normal ranges at the start of the course — as other studies have found[38] — their health was adversely impacted by their studies in law by the early weeks of second semester.[39]

There were, however, statistically significant differences in Ryff’s

wellbeing scores by program. On total wellbeing (an aggregation of

the 6 scales), JD students (x=5.00, sd=.67) had significantly higher scores than

LLB students

(x=4.55, sd=.81), t (272)=-2.67, p=.008. Further, on the sense of

Autonomy scale, JD students (x=5.39, sd=1.12) had higher scores

than LLB

students (x=5.09, sd=1.08), t (280)=-2.99, p=.003. There were no significant

differences in wellbeing levels by year level. While mean scores showed

that first year JD students had higher levels of wellbeing than 2nd

and 3rd year JD students and 3rd–5th year

LLB students, this difference was not significant (at p<.05 level).

Again, this indicates that the adverse impacts of studying law take effect by

the early weeks of second semester,

first year, in a JD program.

Various

socio-demographic variables were also analysed to test whether psychological

health varied across different student groups.

Only gender yielded

significant t-test or ANOVA results on DASS levels. Female students (x=15.11,

sd=8.59) were significantly more stressed than

male students (x=12.79, sd=10.9),

t (271)=-1.81, p=.009, r=.01. However, it is important to note that effect size

was low at the

.01 level. There were no gender differences on the anxiety and

depression scales. Residency did not affect psychological distress: there

were no statistically significant differences between the DASS results of local

and

international students. Finally, there were no statistically significant

differences in the DASS results according to the three categories

of

fee-type: Commonwealth Supported Places, students paying full-fees using

loans, and students paying full-fees using personal or family resources.

Similarly, there were no significant differences in Ryff’s wellbeing

levels on the basis of fee-type, or on the basis of residency

(international and domestic).

The finding that there was no statistically

significant difference in DASS levels by program was surprising given the

differences

between the JD and LLB responses in reported law school experience.

The reported differences between the law school experiences of

JD and LLB

students help to explain why JD students had statistically higher (Ryff’s)

wellbeing rates overall compared to LLB

students. However, we had hypothesised

that improvements in law school experience would reduce the levels of

depression, anxiety

and stress experienced by law students; the data showed that

this hypothesis was unfounded. Despite JD students reporting a significantly

improved experience of law school when compared with LLB students on five out of

six scales, there was no statistically significant

difference in their rates of

depression, anxiety and stress. This finding may indicate that the differences

in experience were not

of sufficient magnitude to make JD students less

distressed than LLB students. Alternatively or additionally, this finding may

indicate

that the areas in which differences were recorded — for example,

satisfaction with being a law student and law school meeting

expectations

— are not the aspects of law school experience that have the most

significant impact on students’ psychological

health. This latter

explanation is supported by qualitative data from the survey and subsequent

focus group discussions.

IV RESPONDENTS’ SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVING LAW STUDENT WELLBEING

Responses to the open-ended survey questions and focus group discussion

questions were thematically

analysed.[40] These questions sought

respondents’ views of the causes of law student distress and asked for

suggestions to improve student

wellbeing. The analysis of responses revealed a

number of concerns and issues common to both programs with four prominent themes

— two major and two minor. Comments and suggestions (in order of

frequency) related to: assessment and feedback; lecturers’

approachability

and understanding of students’ experiences; law school culture and student

activities; and student services.

An additional minor theme emerged that was

specific to the JD program: course flexibility.

Concerns and suggestions

with respect to assessment were the subject of the greatest number of open-ended

comments, from both JD and

LLB

students.[41] These comments ranged

from the need for more continuous assessment and improved timing of assessment

tasks, to the possibility of

increasing the choice in assessment formats. While

a handful of respondents expressed a preference for 100 per cent exams, the

overwhelming

majority of comments were to the effect that 100 per cent exams

were stressful and did not enable students to adequately demonstrate

their

knowledge and understanding. Representative comments on this theme included:

- ‘Seriously. No 100% exams. It’s just cruel to go into something so important and have everything come down to a few hours.’

- ‘More assessment tasks would take the pressure off having to perform exceptionally in one particular task.’

- ‘I really do not think exams with weightings of 70%, 100% are very realistic indicators of student aptitude, nor are they very healthy for students.’

- ‘100% exams are the single biggest cause of anxiety that I have experienced during my degree. They are an awful way to measure aptitude and do nothing other than cause stress and worry.’

A variety of

alternative assessment forms and tasks was requested. Ensuring that assignments

and exams were not scheduled ‘within

a couple of days of each other’

was another common suggestion for improving student wellbeing.

Also on

this theme, respondents felt that the provision of additional, more detailed

feedback during semester would improve student

wellbeing. More information about

grading practices and ‘what was required to get an H1’ was

requested, as were guides

to and ‘models’ of ‘high

quality’ work and increased opportunities for exam practice. A

representative comment

on this issue was: ‘There is a definite lack of

emphasis, support and assistance from lecturers when it comes to preparing

students for law exams and teaching them how to score well.’

It

should be noted that most suggestions on the assessment and feedback theme were

directed toward improving wellbeing by supporting

students to improve their

performance on assessment tasks and gain higher grades (which assumed that

students’ performance

was not normatively assessed). Only one respondent

suggested that the law school should provide clinical legal education ‘so

students realise exam marks are not everything’. Reflecting on the

assessment theme, participants in FGDs commented on the

high levels of stress

generated by marks, their perceived value and students’ high

self-expectations. Unrealistic expectations

and competitiveness related to

marks/results and getting job offers and clerkships were identified in FGDs as

key triggers or contributors

to student depression, anxiety and stress. FGD

participants identified the use of 100 per cent assessment tasks in some

subjects/units

as well as large class sizes as factors that then exacerbate

student anxieties about academic performance and lack of feedback.

The

second major theme in survey responses and FGDs concerned the role that academic

staff can play in relation to student

wellbeing.[42] Respondents suggested

that student wellbeing would be improved by: ‘Teachers engaging and taking

personal interest in students’.

Both LLB and JD students commented that

the development of a rapport or meaningful relationships between teachers and

students would

be desirable. This was linked to approachability and

opportunities for lecturers to get to know students and understand their

experiences

of studying law. It was implied in a number of comments that student

wellbeing would be improved by teachers having an improved understanding

of

students’ concerns and needs, as well as being more approachable and

accessible. Enhanced opportunities for learning, in

and outside the classroom,

were noted to be a benefit of increased access to teachers (such as students had

enjoyed in previous studies).

In this vein, smaller class sizes and

‘safe’ discussion/learning spaces (such as small-group tutorials)

were common suggestions.

Greater understanding of the various commitments that

students are juggling — leading to more realistic expectations on the

part

of lecturers and faculty — was a noted sub-theme. Representative comments

in this vein were [student wellbeing would be

improved if...]:

- ‘The teaching staff were more attuned to the fact that some people have a lot of things to juggle in their lives around law school and try to be supportive and nurturing instead of hard lined about the amount of study we should have done.’

- ‘It feels like the uni expects everyone in the JD to be rich, not working, living in the city, with their parents so no household work or other responsibilities except from university. The reality is that there are many students who are in the entirely opposite situation and there is no support’.

- ‘the expectations made of us were more realistic – for example, the law school makes almost no accomodation for people who have to work, or have any commitments outside of law school – the only people that seem able to cope well are those that have full support’.

FGD

participants echoed these themes and emphasised that academic staff need to

recognise that they can play a major role in helping

students to cope with

stress — for example, by sharing their own experiences of

‘juggling’ commitments and managing

stress, or by encouraging

students to work together and not to compete. Greater lecturer involvement with

respect to student referrals

to professional assistance were also suggested in

FGDs.

The minor themes — law school culture; student services and

JD course flexibility — arose with equal

frequency.[43] In broad terms, it

was suggested that MLS could do more to foster a collaborative and inclusive,

rather than competitive and elitist,

culture. This would be reflected by a range

of activities that addressed and valued ‘diverse students with different

interests’

and activities ‘not focused on law’ but designed to

provide stress relief and/or build social

connections.[44] Activities and

support specifically designed to recognise and assist ‘mature age’

students in the programs was identified

as a particular need. The competitive

selection criteria for participation in the Journals and some Law School Society

activities

were identified as discouraging student involvement in some

extra-curricular activities. Acknowledging and supporting interests

‘outside

of commercial law’ was another suggestion for improving law

school culture and creating a sense of belonging for all students.

FGD

participants identified additional strategies for improving social connections

and faculty inclusiveness. A ‘buddy’

system with later year students

and other cross-year-level initiatives were suggested, and the existing

facilitated study groups

were viewed as a positive basis for collaborative

learning. Diversity, inclusiveness, friendliness, and non-competitiveness were

highlighted as important values that should be actively encouraged and promoted.

In this context, it was suggested that the implicit

messages communicated in a

range of MLS media need to be improved such that all students are seen to be

valued and made ‘visible’,

not only a select few. It was suggested

that acknowledging wide-ranging interests, as well as promoting a broader

experience of law

school and work-life balance would be welcome.

The

activities of the Careers Office were the subject of almost half the comments

related to student services. The broad message was

that students were stressed

about their employment prospects and many would welcome more proactive

counselling about opportunities

‘in and out of law’. Other student

services that were identified as having a role to play in relation to student

wellbeing

included the Student Centre (administration), the Academic Skills

Unit, the Library and Counselling Services. Raising awareness of

and ensuring

access to a range of personal and academic support services were suggested as

means by which student wellbeing could

be enhanced. This extended to calls for

provision of personal tutors/academic mentors, counselling in-house at MLS,

additional support

through the university counselling service, and provision of

mindfulness training. Support for the availability of a qualified Counsellor

within the Law School was balanced, however, by concerns about anonymity: on

that basis, some survey respondents expressed a preference

to attend the central

university Counselling Service. FGD participants identified that student

awareness of the support programs

could be improved by enhancing their

visibility throughout the year at strategic times. Streamlining the ways in

which certain services

are offered, and minimising the bureaucracy associated

with their provision was also suggested. FGD participants also suggested that

there may have been some underreporting of the levels of depression, anxiety and

stress through the survey. A view was expressed

(by professional staff and

student respondents in the FGDs) that law students are poor at acknowledging

symptoms that suggest they

are not coping. Additional information to enable

students to identify symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression was recommended.

Ensuring openness, transparency and honesty with respect to the handling of

mental health issues by professional staff was seen to

be

critical.

Finally, the lack of flexibility in the JD course structure was

identified as a cause of significant stress for a number of students

in that

program. In particular, students with financial and/or family commitments found

the faculty expectation for students to be

on campus four days per week and

attend all classes (as well as weekly lunchtime lectures) to be a source of

considerable stress.

The course workload was widely regarded as excessive, in

some instances requiring students to forgo other important activities and

relationships that would have benefited their mental health. Requests for a

‘reduced-load’ or part-time course plan,

and timetabling that

‘reduced days at uni’ and enabled students to undertake paid work on

2–3 days were week were

frequent.[45]

It is important

to explaining our finding of levels of depression, anxiety and stress that the

first four themes that emerged from

suggestions for improvement of law student

wellbeing engage aspects of the law school experience that are common to both JD

and LLB

programs. This indicates that features of law school life common

to both the LLB and JD programs, rather than the points on which the programs

differ, have a significant bearing on student wellbeing.

Moreover, all five

themes that emerged from analysis of the qualitative data engage issues of

student autonomy, competence and self-esteem,

and the importance to students of

feeling understood and respected by the law school generally and by law teachers

in particular.

These themes differed from the survey questions about law school

experience, which focused on course satisfaction, motivations for

studying law,

engagement with peers, and expectations of law school. Given the quantitative

findings from the survey outlined above,

which indicate that differences on

these measures of law school experience did not have a direct impact on

students’ psychological

health, it is possible that respondents’

qualitative comments have identified aspects of law school experience that have

a

greater impact on psychological health than course satisfaction.

V IMPLICATIONS AND DISCUSSION

Our study found important differences between the reported law school

experience of LLB students and JD students at MLS. Differences

in the mean

responses of the program groups were statistically significant on five of the

six law school experience themes —

Course satisfaction; Peer engagement;

Prepared and present; Academic support; and Expectations of law school. Most

notably, 4 in

5 JD students reported that they derived satisfaction from

studying law, and for two-thirds of the JD students law school had lived

up to

their expectations. By contrast, only 3 in 5 LLB students reported satisfaction

from studying law and only one-third felt that

law school had lived up to their

expectations. This finding helps to explain why, in relation to positive

psychological health, JD

students recorded higher scores than LLB students on

total wellbeing. However, despite the differences in wellbeing as well as

perceived

satisfaction, there were no statistically significant differences in

the levels of depression, anxiety and stress (negative psychological

health)

recorded by each program group.

How is this finding best explained? Some

of the different features and elements of the LLB and JD programs were noted

above. As a

graduate-entry, full-time law degree, the JD is able to be organised

and taught as an integrated program, and the student experience

can be enriched

in a range of ways that are not possible for students undertaking an

undergraduate, combined degree that effectively

creates a part-time law student

for three years.[46] These factors

may account for the higher levels of course satisfaction and academic engagement

recorded by JD students.

However, the full-time graduate course

experience also creates unique stresses and challenges. Some students are older

and are juggling

financial and family responsibilities with a full-time course

load. For some, the ‘cohort experience’ is a mixed one:

the

experience of studying all compulsory subjects with the same student cohort over

two years helps to build social connections,

but it can also contribute to

unhealthy competition among peers and increase anxiety about grades and class

rankings. Nonetheless,

47 per cent of JD respondents agreed that the law school

encouraged students to form healthy and supportive relationships with each

other, while only 17 per cent of the LLB respondents agreed with this

proposition. Moreover, academic workload and high self-expectations

were found

to be causes of stress for students in both programs, not only for JD students

who, as Masters-level students, might be

expected to have high academic

expectations.

In this respect then, program differences do not

offer a strong explanation of the finding that there were no statistically

significant differences in the levels of depression,

anxiety and/or stress

between students in the LLB and JD programs. This led us to turn our analysis to

the features of the law school

experience and the institutional environment that

were common to both the LLB and JD programs and which might have a

greater impact on students’ psychological health than course satisfaction

and engagement. The qualitative responses to open-ended questions seeking

suggestions for improving law student wellbeing were of

particular value in that

respect. In suggesting how student wellbeing could be improved, respondents also

identified what they considered

to be the most important causes or triggers of

psychological distress. As detailed above, the most significant causes of

psychological

distress (areas for improvement) were common to both programs and

identified as: assessment pressures and (perceived lack of) feedback;

a

perceived lack of understanding and approachability on the part of

lecturers/faculty; the fact that the law school culture and

many student

activities are perceived as exclusive and competitive; and limitations in the

forms and levels of support offered by

student services. In addition, JD

students identified the lack of flexibility in their course structure as a cause

of significant

stress. These themes point to the importance for students’

psychological health of: experiences of success and achievement

(or at least

competence); and feeling understood, supported and

‘belonging’.

In this respect, our qualitative findings add

support to an important strand of the existing research into law student

wellbeing —

Self-Determination Theory or ‘human needs’ theory

— which argues that psychological distress in law students occurs

because

their needs for experiences of ‘competence’, ‘autonomy’

and ‘relatedness to others’ are

not

met.[47] As Sheldon and Krieger

explain:

According to SDT, all human beings require regular experiences of autonomy,

competence, and relatedness to thrive and maximize their

positive motivation. In

other words, people need to feel that they are good at what they do or at least

can become good at it (competence);

that they are doing what they choose and

want to be doing, that is, what they enjoy or at least believe in (autonomy);

and that they

are relating meaningfully to others in the process, that is,

connecting with the selves of other people

(relatedness).[48]

Given the

analysis of our qualitative data above, it is certainly plausible that

students’ sense of competence is undermined

by law school assessment and

grading practices. It is also possible to see that relatedness is undermined by

the culture of many

law schools, including that at MLS, which is perceived as

promoting a narrow and elitist paradigm of ‘success’ that inevitably

creates ‘winners’ and ‘losers’.

Moreover,

Self-Determination Theory has established that psychological need satisfaction

(experiences of competence, autonomy and

relatedness) is fostered in social

contexts that are ‘autonomy supportive’ and inhibited in social

contexts that are

‘controlling’.[49]

According to Self-Determination Theory, social environments and relations that

are autonomy supportive are distinguished by:

(a) choice provision, in which the authority provides subordinates with as

much choice as possible within the constraints of the task

and situation; (b)

meaningful rationale provision, in which the authority explains the situation in

cases where no choice can be

provided; and (c) perspective taking, in which the

authority shows that he or she is aware of, and cares about, the point of view

of the subordinate...[50]

Applied

to our study findings, the second theme in respondents’ suggestions above

could now be described as a lack of ‘perspective

taking’ on the part

of lecturers and faculty. The assessment and feedback and (JD) course

flexibility themes also speak to

a perceived lack of choice provision and/or

meaningful rationale. In short, there is considerable support for the hypthesis

that

our students — including those who derive satisfaction from studying

law — perceive the law school as controlling (rather

than autonomy

supportive) and that this undermines opportunities for experiences of

competence, autonomy and relatedness, resulting

in significant levels of

psychological distress.

Law schools are typically perceived by their

students as controlling, and Sheldon and Krieger’s research established

that law

students’ perceptions of the controlling or autonomy-supportive

nature of their school and law teachers had a direct effect

on student

wellbeing.[51]

Further research

would be needed to directly test whether common perceptions of control/autonomy

support among LLB and JD students

at MLS explain the similar levels of

depression, anxiety and stress among the student cohorts, negating the

significantly different

levels of satisfaction and engagement with their studies

in law.

VI CONCLUSION

The fact that Law Schools are a ‘breeding ground for depression,

anxiety, and other stress-related

illnesses’[52] is now widely

accepted in Australia and

internationally.[53] Moreover,

depression and psychological distress among law students has come to be

understood as a ‘teaching and learning’

issue, rather than only the

affected individual’s problem, because both depression and high levels of

stress are known to affect

the ability to concentrate, which in turn adversely

impacts on the ability to learn and retain

information.[54]

High levels of stress can also lead students to ‘distance’

themselves from law school activities and practice ‘avoidance

tactics’, such as skipping classes, thereby creating excuses for failure

in order to protect self-esteem.[55]

Moreover, the relation between academic performance and student wellbeing is

multi-directional: disappointing performance may cause

anxiety and depression;

and negative feelings are likely to interfere with academic performance. As

Iijima notes, ‘[b]ecause

emotional state and academic performance are so

closely related ... students may get caught in a downward spiral of emotional

and

academic problems’.[56]

Research attention is turning to understanding the features of law

school that cause and aggravate students’ psychological distress,

and to

designing effective interventions. A diverse range of factors have been

identified as potential sources of stress for law

students — from large

class sizes and low levels of student-teacher interaction, to intense academic

competition and high self-expectations,

to the increasing debt load and

declining job market.[57] These

sources of stress can be exacerbated by a failure to access available support

and assistance.[58] While it is

sometimes argued that the stressful nature of law school is good preparation for

working in the legal profession, or

that it ‘weeds out’ those

unsuited to legal practice, there is no evidence that those who suffer from high

levels of

stress, anxiety or depression during law school discontinue their

courses or abandon their plans to work in the profession. Instead,

the rates of

depression, anxiety and stress in the profession indicate that people affected

by these conditions during law school

go on to enter the profession despite its

impact on their mental health.[59]

Nor is there evidence that the experience of stress teaches people how to manage

it effectively. Again, the comparable rates of mental

distress among legal

professionals and law students indicate that many people suffer from stress,

anxiety and depression without

improving their skills to manage, reduce or

prevent it.[60] Thus, as Jennifer

Jolly-Ryan suggests, it is possible that ‘[w]hat happens during law school

forms the foundation for a lifetime

of bad habits and dysfunctional

behaviours’[61] It certainly

appears that a number of students, and lawyers, accept discomfort and depression

as part of the ‘cost’ of

becoming a

lawyer;[62] it is imperative that

this is not a lesson ‘taught’ by law schools.

In order to

design effective interventions to improve law student wellbeing, a deep

understanding of the causes or triggers of psychological

distress is needed. Our

empirical findings were somewhat surprising in that improved levels of course

satisfaction and engagement

did not result in reduced levels of depression,

anxiety and stress. Indeed, it appears that law students can be

‘happy’

with their course while experiencing considerable levels of

psychological distress. Students’ open-ended responses gave additional

insight into the factors common to both the LLB and JD programs that may be

adversely impacting on student mental health. These factors

— assessment

anxiety, lecturers’ lack of understanding, an exclusive law school culture

and course inflexibility (JD)

— give support to Self-Determination

Theory’s explanation of psychological distress. In particular, Sheldon and

Krieger’s

2007 study established that lecturers’ attitudes to their

students, and in particular the level of autonomy-support they provide,

is

important for law student wellbeing. The present study indicates that this

theory of law student distress has merit and warrants

further investigation with