University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

A Force for Globalisation:

Emerging Markets Debt Trading from 1994 to 1999

By

Ross P

Buckley[1]

Forthcoming, Fordham International Law Journal.

This paper analyses the development of the secondary market in emerging markets debt from 1994 to 1999, and identifies the lessons to be learnt from that period. Particular attention is paid to the increasing integration of the secondary market with traditional financial markets, and to the force for globalisation that this secondary market therefore exerted in the period.

The secondary market in emerging markets debt is based in New York and London and grew out of the swapping among banks in 1983 of the loans of the debt crisis. The author has previously chronicled the development of the market from 1983 to 1993,[2] and analysed several of its aspects.[3] This paper analyses the market history 1994-1999, identifying the lessons learnt from that period of market development. Particular attention is paid to the increasing integration of the secondary market for emerging markets debt with traditional financial markets, and to the force for globalisation that this secondary market therefore exerted in the period.

The year, 1993, witnessed an extraordinary bull run in the secondary market for emerging markets debt.[4] The bull market continued through the New Year into 1994 with the Salomon Brady bond index jumping an extraordinary 15.75 percent in January, 1994.[5] In that month there was a revolt in Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state, but the market’s upward trend barely hesitated, at the time, on this evidence of political instability. It was the risk of inflation to Mexico’s north, not ill-treated peasants in its south, that was to end the bull run.

Notwithstanding the strong performance in January, by June 1994 the Salomon Brady bond index had fallen 33 percent for the year[6] and loan prices had fallen further with Russian and Peruvian loans down almost 50 percent.[7] The magnitude of these price falls owed much to their inflated values at the end of 1993. The boom of 1993 had been fuelled in part by low interest rates in the U.S. that saw fund managers and other investors seeking higher returns in the emerging markets. The turnaround in this interest rate environment was the major factor in the market collapse of 1994. The other important factors were the excesses of 1993, particularly excessive leverage, and the political risks displayed in Mexico and Venezuela. Each will be considered.

On February 4, 1994, in an effort to curb potential inflationary pressures, the U.S. Federal Reserve increased short-term interest rates.[8] The rates continued to climb throughout 1994.[9] As interest rates rose, U.S. Treasury bond prices fell accordingly, and emerging market bonds, which had for some time been priced at margins above U.S. Treasuries,[10] fell precipitately. This movement was exacerbated by the narrowing in 1993 of the spread between emerging market and U.S. Treasury bonds: while the yield on the US long bond declined some 104 basis points in 1993, the spread between it and emerging markets bonds, on average, declined a dramatic 413 basis points.[11] As U.S. rates moved upwards in 1994, and U.S. long term rates rose 126 basis points in the first half of the year,[12] investors suddenly found the price differential between emerging market and U.S. instruments grossly inadequate to compensate for the increasing risk on display south of the border.

The bull run of 1993 was, by any measures, extraordinary. The Salomon Brady bond index rose 44 percent during 1993, and a further 15 percent in January, 1994.[13] The prices of many loans increased even more dramatically. Peruvian loans, which had sold for 20 cents on the dollar in early 1993, were trading above 70 cents in early 1994.[14] Peru was not servicing its loans, so these prices were a gamble on a Brady-style restructuring in which Peru would decide to meet its obligations. Russian loans were at equally unrealistic prices.[15] However, recent restructurings had proven notoriously slow to complete. Brazil’s had required over a year longer than anyone anticipated. Paying these prices for non-performing loans purely in anticipation of a restructuring was unalloyed, high-risk speculation.

Many market investors were also highly leveraged in 1993.[16] As Bill Nightingale said,

The US stock and bond markets have regulatory limits on how much systematic leverage there can be -- the emerging markets have none. It’s purely between the investors and the dealers to determine how much leverage they want to take. There was a hell of a lot in this market, and probably much more than ... in any well-regulated market.[17]

Hedge funds and other risk-friendly institutional investors had taken large positions in Brady bonds on margin. A number of banks had leveraged their clients, both institutional and individual investors, by up to 900 percent.[18] These investors tended to look upon Brady bonds as high liquidity instruments that could be sold immediately upon a change in the interest rate environment.[19] However, in a falling market, buyers proved to be very scarce indeed. The depth of panic in the market is evidenced by the fact that the prices of floating-rate Brady bonds fell virtually as far as fixed-rate Bradys, even though floating-rate bonds that trade at deep discounts would normally rise in value in a rising interest rate environment.[20] Buyers were simply too rare to support the market.

In addition to the investors who were forced to sell to meet margin calls, others who had purchased Brazil’s when-and-if-issued Brady bonds at high prices in late 1993 also had to sell as market prices were substantially lower when completion of the long-awaited restructuring neared.[21] Counterparty defaults added further to trader’s losses in 1994. Many participants had joined the market in the bull run and had no experience of, and inadequate capital to withstand, an emerging markets collapse. The resulting defaults made trading even more expensive and difficult for the remaining participants.[22]

In summary, in the bull run of 1993 investors forgot the historical volatility of emerging markets and their history of defaulting on their debts. Brady bonds were liquid instruments, traded in Euroclear and Cedel, and it was all too easy to believe that there would be buyers when one wanted, or needed, to sell.[23] However, many of the institutional investors which had discovered emerging markets debt in the halcyon days of 1993 got out of the market more quickly than they had got into it, and the primary source of demand which had buoyed the market throughout 1993 was suddenly mostly gone.[24]

The Chiapas uprising in 1994 underlined the political uncertainty of the region. Political risk in international finance usually refers to the risks associated with the stability of government and governmental decisions. In Mexico political risk also had a more literal meaning: 1994 was an election year and in March the ruling party’s presidential candidate, Luis Donaldo Colosio, was assassinated.[25]

In Brazil, 1994 was also an election year and early polls showed a populist left-leaning candidate in the lead.[26] The spectre of a retreat from economic austerity and the threat of a return to hyperinflation shook the market. Furthermore, a radical new economic plan, and a new currency, the Real, were introduced in July.[27]

In Venezuela, the banking system went into crisis and the government responded with a bailout which cost some 10 percent of GDP. Venezuela’s economy was in dire straits and default on its Brady bonds was a real and imminent prospect.[28]

Finally, to cap off a year which thrust political risk before investors without respite, in September there was a second assassination in Mexico, of the secretary general of the ruling party, Francisco Ruiz Massieu.[29]

By early December, most emerging markets debt traders were consoling themselves with the thought that at least things could not be worse in the market in 1995. They were wrong.

As 1994 drew to a close, Mexico was spending its foreign exchange reserves heavily to defend the value of the peso. These reserves, $30 billion in February, had declined to around $11 billion by December, 1994.[30] The overvalued national currency could no longer be supported and on December 19 the new Mexican government let the peso float against the dollar, resulting in a substantial devaluation.[31] In addition, the Mexican stock market fell over 40 percent in the first quarter of 1995,[32] and Mexican Brady bonds and eurobonds fell so far that at one stage dollar-denominated eurobonds issued by prime Mexican banks were yielding 2,500 basis points over U.S. Treasury bonds.[33] The common refrain of traders in January 1995 was that “it was almost a freefall ... I’ve never seen anything like it”.[34] This spoke to the general inexperience of the traders, as the market had been through it all before, in October 1991.[35] However, that crash was but a memory of the few “veterans” who had been in the market that long.

There are three major reasons the devaluation became necessary: (i) the previous administration had long left the peso overvalued to curb inflation;[36] (ii) Mexico’s short-term indebtedness had been growing so that it amounted to some 35 percent of its total debt, and its refinancing was proving increasingly difficult[37] as the many adverse factors at play in 1994 conspired to direct foreign capital away from Mexico; and (iii) over the preceding three years Mexico had accumulated a balance of payments deficit of over $90 billion, a deficit approaching that of the rest of Latin America and Asia combined, and was financing it by the sale of securities to U.S. investors, which throughout 1994 became increasingly difficult and expensive.[38]

Ironically, “commentators, economists and finance professionals had been calling out for a Mexican peso devaluation for some time”.[39] A crisis was caused by a development that the experts had been recommending but the inevitably of which the financial markets, replete from a year of profits, did not want to acknowledge. Indeed, even as late as November 1994 journalists were writing, “For Western investors the message is: buy ... the potential of most emerging markets [is] beyond doubt.”[40]

The Mexican peso crisis happened one month later.

The United States quickly assembled an international financial rescue package. Over $50 billion of credit support was provided for Mexico: $20 billion from the U.S. through its Exchange Stabilization Fund[41] and the balance from the I.M.F., the Bank for International Settlements, the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank and Canada.[42] This rescue package had a dramatic effect on the secondary market. On the day President Clinton announced the package Mexico’s par bonds rose from 44 cents to 55.5 cents and its discount bonds from 56 to 72.5 cents. The prices of other emerging nations’ debts rose likewise.[43]

Nonetheless, the flow-on effects of Mexico’s troubles were so severe that, even with time for reflection, financial journalists were writing that “Mexico had almost single-handedly destroyed the emerging markets as an investment class”.[44] How could one country almost destroy an entire market by itself? The answer was an effect named by someone who had overindulged in the oily indigenous alcohol of Mexico and paid the price.

Mexico’s problems in late 1994 and early 1995 were transmitted to other emerging markets with a speed and severity which few expected, and which was labelled the Tequila Effect.[45] The debt of almost all emerging markets, from Eastern Europe to Asia, was in the first months of 1995 affected by the Mexican devaluation and subsequent problems.[46] Argentina was the hardest hit, but the contagion spread through most of Latin America and Eastern Europe and much of Asia.[47]

Argentina suffered from capital flight “of staggering proportions” as “[m]uch of the flight capital that had returned to the country flew out again.” [48] In addition, “[s]hort-term capital, much of it American, stampeded out on fears of a return to hyper-inflation and a breakdown in ... dollar convertibility”.[49] This led to the collapse of a number of banks, and the government was soon seeking an international rescue package which when granted comprised some $11.4 billion.[50] In Thailand the baht came under sustained pressure and required massive support from the central bank to avoid a devaluation. Polish Brady bonds fell 7.8 percent and Bulgaria’s over 10 percent, the Philippines stock market fell over 17 percent, Hong Kong’s some 15 percent and the stock markets of nations as diverse as China, Hungary, India, Pakistan, Peru, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey all fell over 10 percent in January as funds withdrew generally from emerging markets.[51] Most East Asian nations, in particular, worked hard to distinguish their economies from Mexico’s as their stock and bond markets took a battering.[52]

Yet the economies of these countries shared little in common with Mexico. Argentina and Hungary were identified as having large and growing current-account deficits but far less of their deficits were financed by short-term capital -- a crucial part of the Mexican equation.[53] In part the tequila effect arose because many fund managers had invested heavily in Mexico and less so in the other emerging markets but, needing cash to meet margin calls and redemptions in Mexico, sold in the other markets.[54] Mostly, however, in the words of fund manager, Isabel Saltzman, “[i]t was the classic panic market”.[55] The tequila effect “was a sobering reminder that big institutional investors were looking at all ‘emerging markets’ from Santiago to Seoul through a single lens”.[56]

Recovery from the tequila effect took time.[57] Latin sovereigns were issuing debt, admittedly at very high spreads, as early as May, 1995[58] and bond issuers were active in the markets in the second half of 1995. However, Brady bonds traded at extraordinary yields throughout most of 1995. For instance, the stripped spreads (the spread after deduction of the collateral guarantees over that of comparable US Treasury bonds) for the Bradys of the major Latin nations exceeded 1,000 basis points for most of 1995 and, in October, still exceeded 1,250 basis points for Argentine Brady bonds.[59]

The peso crisis and tequila effect led to dramatic growth in asset securitisation throughout the region. Companies from Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and elsewhere raised funds through the securitisation of cash flows from export contracts for many products.[60] Asset securitisation proved to be an efficient and attractive way for emerging market entities to raise funds upon the credit risk of the contractual counterparty from a developed nation.

Prosperity and relative stability returned to the market in 1996 and these factors, coupled to the relatively low interest rates on offer, prompted debtors to seek to retire some of their Brady bonds and liberate the capital tied up in their collateral, and prompted a resurgence in syndicated lending to the emerging markets.

In April 1996 Mexico offered to exchange new 30-year global bonds for dollar-denominated Brady par and discount bonds. The exchange was structured as a modified Dutch auction and Mexico accepted offers for $1.75 billion of the new bonds at a spread of 552 basis points over U.S. Treasuries. This gave a yield of 12.4 percent.[61] The par bonds, which paid 6.25 percent, were exchanged for 67 cents on the dollar and the discount bonds, which paid Libor plus 13/16, at 80.6 cents.[62] This exchange resulted in the retirement of some $2.4 billion of Brady bonds.[63]

The exchange offer removed one of the enduring anomalies of the Brady bonds -- the amalgamation of U.S. and emerging market sovereign risk in the one instrument. This hybrid nature of Brady bonds always made them difficult to value and while the zero coupon bonds which provided a partial interest and principal guarantee could be stripped out (usually by shorting them) this was an expensive and inefficient process. In the words of Merrill Lynch,

“Brady bond structures were the result of complex negotiations between the restructuring countries and commercial bank advisory committees, with little consideration of their future marketability to traditional bond buyers. In the case of collateralized bonds, the result was a collection of inefficiently bundled attributes whose resulting value to most investors is lower than the all-in servicing cost to the issuer. ... Given the ... size of the Brady bond market, these structure choices are probably among the costlier marketing mistakes in bond history.”[64]

The Brady bond exchange appealed to Mexico for four reasons:

1. It allowed Mexico to access some of the collateral tied up in the Brady bonds. In the words of one Mexican finance ministry official: “It is inefficient to have $9 billion of our cash invested in US Treasuries when we can invest that money to cancel more expensive debt”.[65]

2. It reduced the stock of Mexican debt by $1.25 billion - there was some $600 million less of the new bonds because the Bradys were exchanged at discounts and the $650 million of zero coupon bonds used as collateral could now be used to retire short-term, and more expensive, debt.[66]

3. The new bonds established the long end of an extended, well-distributed, non-Brady yield curve for Mexican debt and proved there was investor appetite for 30-year non-collateralised Mexican risk.

4. Mexican officials claimed a further inducement of the exchange was to extend the tenor of their debt from 2019, when the Bradys were due to mature, to 2026.[67] As repayment of the Bradys was fully secured by zero-coupon bonds, this is a spurious factor although the exchange did, in facilitating the retirement of some $650 million of short-term debt, improve Mexico’s debt profile.

The exchange offer appealed principally to sophisticated institutional investors which already held Brady bonds but sought undiluted Mexican risk with higher yields.[68] There was very little participation by commercial banks and only around 24 percent of the issue went to Mexican banks.[69]

Somewhat extraordinarily, Mexico’s principal bankers for the past century and the architect of its Aztec and Brady bonds, JP Morgan, was not involved in this exchange which was managed by Goldman Sachs and co-managed by Salomon Brothers, Chase Manhattan and Deutsche Morgan Grenfell. The deal represented a real coup for Goldman Sachs, never before a noted emerging markets house.

As usual, Mexico’s initiative established a trend. In September 1996 the Philippines gave Brady bond holders the option of exchanging their 25-year collateralised Brady bonds for 20-year fixed rate uncollateralised bonds. The Philippines accepted $635 million of the Brady bonds, one-third of those outstanding, and $137 million in new money as the new bonds were also able to be acquired for cash.[70]

Brazil launched its Brady exchange in June 1997 issuing $3 billion of 30-year unsecured bonds priced at 395 basis points over U.S. Treasuries.[71] One-quarter of the new bonds were sold for cash and the balance, $2.25 billion, were swapped for some $2.7 billion of Brady bonds.[72] The exchange, arranged by Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, liberated collateral worth $605 million.[73]

In September 1997, only weeks before the contagion from the Asian crisis spread through the emerging markets, Venezuela effected the largest exchange to date. It swapped $4.4 billion of Bradys for $3.68 billion of new 30-year bonds with a coupon of 9.25 percent and sold further new bonds for cash.[74] The exchange retired over one-half of Venezuela’s Brady bonds.[75] Argentina followed the leader, exchanging $1.75 billion of new unsecured 30-year bonds for its Brady bonds and Bocones, domestic dollar-denominated bonds, and selling a further $500 million of new bonds for cash.[76] Finally, Panama rounded out a hectic September, swapping $700 million of new 30-year bonds, at a spread only 250 basis points above U.S. Treasuries, for its Brady bonds. This was a quite remarkable transaction given that Panama’s Brady-style restructuring had only occurred in July 1996 and its Brady bonds were then issued at a 565 basis point spread over Treasuries.[77]

In mid-1991, John Reed, chairman of Citicorp, said that notwithstanding the need of developing countries for capital, the environment for cross-border lending was “inherently hostile” and would not change for at least a decade.[78] He was wrong. In 1990 there had been $14.9 billion of commercial bank loans to developing countries. The figure by 1996 was $36.5 billion and in 1997 there were $49.4 billion of commercial bank loans to developing countries.[79] The reasons for this re-emergence of lending to emerging markets are fourfold: (a) The peso crisis and tequila effect in 1995 made bond issuance difficult for many emerging markets debtors and the debtors actively sought loans. Indeed, for the first time since the debt crisis, in 1995 more capital was raised by loans than bonds;[80] (b) Asia accounted for most of the loans - only $25 billion of the total of $135 billion went to Latin America – and many of the loans were to private sector corporations and some were securitised by receivables;[81] (c) the commercial banks had been enjoying strong earnings for some time and were at peak liquidity; and (d) generally there was lots of capital in the system. [82] As always, capital flows to emerging markets are determined by liquidity in the developed nations - the demand is always there, it is the supply side that determines lending volumes.[83]

There were some significant differences between these loans and those of the 1970s.[84] The earlier loans were invariably unsecured. These loans are usually either secured in some way, or, if to a sovereign, for a specific income producing purpose. Security is most often attained by securitising receivables or structuring the loan as project finance. The days of financing the consolidated revenue of debtors are, thankfully, largely gone. Syndicated lending even survived the Asian crisis -- on April 1, 1998 the Export Import Bank of Thailand signed a $1 billion facility with 64 banks priced at 80 basis points over Libor, admittedly supported by a guarantee from the Asian Development Bank.[85]

Citibank was the first to establish a specialist trading desk for emerging markets loans in March, 1997. Other active institutions include Chase Manhattan, JP Morgan, ING Barings and Merrill Lynch. The difference between these and conventional emerging markets desks, which while principally dealing in bonds still do deal in loans, is that the new desks deal with syndicated loans made in the previous few years which trade at par and are performing – or, at least, which did and were until the Asian crisis.[86] As one would expect, the market was still thin and bid-offer spreads relatively wide at one-quarter to one-half a point.[87]

A new industry body, the Loan Syndications and Trading Association, was established in New York in late 1995 to promote and regulate secondary market trading in U.S. and European bank loans,[88] and the Loan Market Association was founded in London in 1996 to foster secondary market loan trading in Europe. Each association has devoted considerable attention to trading in emerging markets loans[89] which is interesting given the considerable overlap with EMTA’s work.[90] EMTA provided organisational and other technical support to the Loan Syndications and Trading Association in its early years.[91]

Accounts of this “emerging” secondary market in emerging markets loans make amusing reading. Articles written in 1997 with titles like “The newest game in town” present secondary loan trading and the problems in trading loans as opposed to bonds as if they were novel and not the daily fare of this market in the 1980s.[92] The financial markets have a radio-active memory, with a very short half-life.

Few predicted the economic crisis which commenced in Asia in 1997,[93] and almost no one predicted its severity.[94] Western capital had poured into emerging markets in record quantities in the preceding two years. Emerging markets stocks and bonds were being acquired by investors scornful of the low interest rates on offer in their home countries and fearful that the U.S. stock market had reached unsustainable heights.[95] The substantial risks which history as recent as 1995 taught were inherent in emerging markets instruments were simply not being factored into their pricing. This meant any generalised market scare was likely to have a major impact. It did.

The Asian problems began in Thailand in June 1997 and soon spread throughout the region. Nonetheless, it was not until October that the currency crisis, as it was then termed, deepened across the sector. Whether it is Wall Street in 1929 or 1987, or this secondary market in every year between 1991 and 1997,[96] October seems a bad month for financial markets. Perhaps this is due to the tendency of many trading accounts to begin to book the profits made that year in advance of the year end.[97] Whatever the cause, “beware the ides of October” should perhaps be tattooed on every fund managers’ and traders’ forearm: the major U.S. banks alone reportedly lost some $400 million trading in the emerging markets in October, 1997.[98]

The precipitating event this October was intense speculation on the Hong Kong dollar which, in turn, triggered a sustained plunge in Hong Kong share prices.[99] Once the contagion spread, it spread widely, to London and Wall Street and throughout the emerging markets.[100] Brazil’s Brady bonds fell in value 17 percent in the last ten days of October and leading Latin American mutual funds lost 17 to 20 percent of their value in a week.[101] It was as if Asia was retaliating for the tequila effect of 1995 by sending emerging markets globally into a tailspin,[102] and, just as in 1995, while the economic correlations between regions were weak, the psychological correlations were strong. Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico were all affected with Brazil the hardest hit as it shared problems like a large current account deficit with the troubled Asian countries. Quick strong action by Brazilian authorities and prompt action by the authorities in the other countries, principally by tightening monetary and fiscal policies, restored market confidence and staunched the drain on foreign exchange reserves.[103] Accordingly, the contagion did not significantly damage the domestic economies of Latin American countries, or East European ones for that matter. That East Asia’s hangover did not spread to other emerging markets on anything like the scale of the Tequila Effect suggested a pleasing maturation in the secondary market.[104] Nonetheless, the shift in investor perception of the risk inherent in emerging market assets means that corporations and sovereigns from these nations are now paying substantially higher interest premia to raise capital.

The sell-off was so intense that many brokerages were overwhelmed and EMTA recommended that brokerages close 30 minutes earlier on October 29.[105] An indication of the volatility is given by the composite stripped spread on JP Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond Index which went from a pre-crisis 334 basis points on October 22 to 695 basis points by November 12.[106] Nonetheless, while a doubling in spreads is extreme, the October sell-off was, in part, merely correcting the anomalous and grossly excessive spread compression which had characterised the market since 1996.

The panic selling that had characterised the market in early 1995 was less prevalent in October, 1997.[107] This time the institutional investors showed the maturity and belief in the market that everyone wished they had shown two years earlier. Nonetheless, while many institutional investors did not dump large chunks of their portfolios in late 1997, neither did they return at all quickly to the market to increase their exposure to the sector.[108] While traders were pleased with, and somewhat proud of, this new-found maturity of the market’s principal investors, the market itself decayed quite severely in October, 1997. The error rate in matching trades was unacceptably high which delayed the settlement of many trades and bid-offer spreads widened dramatically to well over two percentage points.[109]

The crisis turned the clock back in the secondary market. As many of the most recent new investors left the market and spreads widened, the traditional emerging markets money returned.[110] Spreads of emerging markets bonds over comparable U.S. Treasury’s averaged 5 percent in March 1998, compared to 3.3 percent before the Asian troubles.[111] The Asian Crisis also turned back the clock further in other ways, back as far as 1982 in fact. Once again, once trouble broke, the international banks turned off the tap on new lending so decisively that a crisis became inevitable. The five most troubled Asian countries received $100 billion less in 1997 than in 1996, with South Korea alone receiving $50 billion less.[112] Many top U.S. corporations would struggle to survive such diminished access to debt financing; its impact on developing nations so drastic.

While poor prudential regulation in the debtor countries and misjudgments among creditors clearly contributed to the crisis, this was in no conventional sense a debt crisis.[113] It was initially a currency crisis[114] and developed into a more generalised economic crisis, at least for Indonesia, Thailand, and Korea, the three most severely affected countries.[115] However, while this was not a regional debt crisis, indebtedness did play a role in the troubles. The stock of debt in the region increased 12 percent in each of 1995 and 1996[116] and private commercial debt (debt not backed by a sovereign guarantee) increased a remarkable 50 percent from January, 1995 to December, 1996.[117]

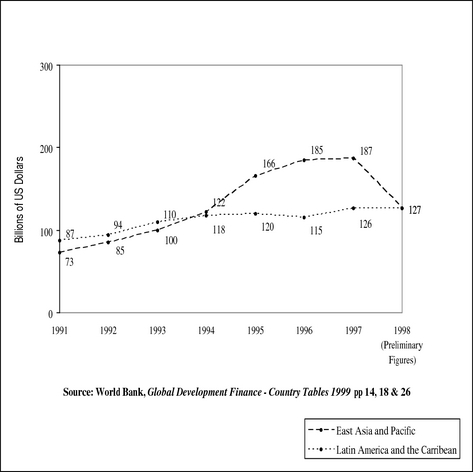

Short-term indebtedness increased significantly in 1995 and 1996 across the region, although the increase was concentrated in China, Indonesia and Thailand.[118] The rapid increase in short-term debt in East Asia was not matched by Latin America, as seen in Figure One below – perhaps one of the few benefits of Mexico’s peso crisis and the Tequila effect. Indeed, it is likely that short-term debt flows to East Asia in 1995, 1996 and early 1997 were buoyed by Mexico’s troubles and the pall they cast over Latin America.[119]

Figure One --

The World Bank has concluded that, “[t]he buildup of short-term, unhedged debt left East Asian economies vulnerable to a sudden collapse of confidence ... The loss of confidence led to capital outflows, and thus to depreciating currencies and falling asset prices, which further strained private balance sheets and so proved self-fulfilling.”[120]

The buildup of short-term debt was not a region-wide phenomenon. The ratio of short-term debt to total debt in the countries of the region in mid-1997 ranged from 67 percent in Korea and 46 percent in Thailand, to 24 percent in Indonesia and 19 percent in the Philippines.[121]

The proliferation of investment in local currency local instruments definitely intensified the global contagion. The Asian Crisis began as a currency crisis and the decimation a substantial devaluation causes to a local currency portfolio naturally prompted a severe sell-off at the first sign of trouble. This was compounded by the tendency of many local currency local instruments to be of short duration for which, as the storm clouds gathered, the prospects of refinancing were slight.[122]

The big events in 1998 were the Russian repayment moratorium on foreign debt and devaluation of the rouble in August and the collapse of the major hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management, in September. In Frederic Haller’s words,

“Last year [1998] was just about the worst that the emerging debt market has ever experienced. In particular, the Russian debacle in August ... was the defining moment of 1998”.[123]

In stark contrast to Asia the previous year, the contagion from Russia’s crisis was severe, far eclipsing the Tequila effect of 1995.[124]

By 1998 Russia’ economic and political problems had been mounting for some years. The radical reforms required to allow markets, not bureaucrats, to allocate resources were proving problematic for this former command economy burdened, as it was, with a deteriorating current account, tax collection problems, debt management problems, low oil prices, and industrial unrest.[125] In addition, there was considerable political instability arising principally from a sizeable bloc in parliament who sought to return the economy to the old system. Coupled to all this were the risk weightings under the Basel Capital Adequacy Accord which made loans to Russia attractive by weighting loans to OECD sovereigns at zero.[126] In the words of one senior banker, “your average loan commitment officer could hit his return on capital targets much easier offering money to Boris [Yeltsin] than he could lending to GECC”.[127]

In May 1998 declining investor confidence forced the Central Bank to raise interest rates to support the rouble. By July the central bank had been forced into extensive sales of its hard currency reserves to defend the rouble. In mid-August, 1998, the Russian Central Bank announced a widening of the band in which the rouble would be allowed to float. In effect this was a devaluation. In addition, the government declared a 90-day moratorium on the servicing of foreign debt by Russian firms.[128] Although most headlines at the time focussed upon the devaluation, the issue of vital concern to investors was the moratorium. Devaluations are a market risk, moratoria are a political one which in this case was seen as a policy choice to favour local banks over foreign investors.[129]

While Russia’s economic problems had been apparent for some considerable time, the market believed Russia would not be allowed to fail. In the words of Desmond Lachman: “Bulgaria didn’t fail. Thailand didn’t fail. Indonesia didn’t fail. But now Russia fails ... the IMF and the Group of Seven are no longer there as a backstop.”[130] In essence, the Russian crisis was a classic instance of moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs whenever a situation rewards investors for financial misbehaviour.[131] In the case of Russia, investors expected to be bailed out. In the words, again, of Desmond Lachman,

“Anybody who questions that Russia’s fundamentals were worthy of investment ... wasn’t operating in the markets at the time. ... Most [investors] who did take positions on Russia were doing this on the argument that Russia was too big to fail and that the G-7 nations would ... bail them out.”[132]

The proper operation of the market, which may have led to a more gradual withdrawal from investing in Russia, was profoundly affected by the moral hazard of an anticipated bail-out.[133] Russia’s geo-political signficance, in particular, meant investors were very confident that it would not be allowed to default on its financial obligations.[134] Indeed, even four months later, EMTA’s co-chair, Frederic Haller, was railing that, “The failure of the IMF and G-7 to show timely leadership in Russia in August may prove to be the biggest international policy mistake of the post-Cold War era.”[135]

The extraordinary aspect of Russia’s crisis was the fallout from it. Russia’s economy is not large, about the size of Spain’s or Switzerland’s.[136] Yet the consequences of Russia’s devaluation and moratorium were to stand the international bond markets on their heads.[137] In August, emerging markets debt fell over 28 percent in value, high-yield bonds fell over 7 percent, and real estate investment trusts that invested in mortgage securities fell about 27 percent. Meanwhile, U.S. Treasury bonds increased over 2 percent.[138] Russia’s collapse resulted in a tremendous flight to quality and this time investors went all the way to the security of US Treasuries. Even the bonds of the blue chip corporate sector offered insufficient security to bondholders in August and September, 1998.

How can one explain such profound effects from the events in one small to middling economic power? In part, the answer lies in the approaches to risk of the large investors, and this factor has three elements.

The first was an over reliance on the then new, sophisticated risk management techniques. Many funds and other investors, believing they could calculate their risk levels precisely, strove for yield and discounted risk as something that was now manageable.[139] However, contemporary risk management models assume a high level of liquidity[140] which history teaches us may not be there in times of crisis in the emerging markets and which was missing in August and September 1998.

The second element of the risk strategies of large investors was the common strategy of hedging against losses in emerging markets debt by going short US Treasuries[141] on the assumption that prices of emerging markets and US bonds historically moved in tandem.[142] The flight to quality that followed Russia’s collapse sent the yield on 30-year US Treasuries to the lowest levels since the US began issuing the bonds on a regular basis in 1977[143] while the yields on emerging markets bonds soared. As bond yield and price are inversely related, investors adopting this strategy found themselves long on emerging markets bonds which were falling in price rapidly and short US Treasuries which were increasing in price. As we shall see, this was a pincer sufficient to squeeze the capital out of even the biggest hedge funds.

The third element of the risk strategies of large investors was their appetite for leverage. Investors with highly leveraged positions in Russian assets were forced to sell other assets to cover margin calls or otherwise repay the debt incurred to invest in Russian debt. The other assets sold were most often, though not always,[144] in other emerging markets.[145] Accordingly, the continued appetite for leverage among many investors in the emerging markets means that a severe fall in one emerging market rebounds through the entire market, almost irrespective of the economic health of the other sectors.[146]

Another part of the reason Russia’s actions had such far-reaching consequences was that its heavy debt issuance had given it a high profile in the principal index. By spring of 1998 Russian debt accounted for one-seventh of JP Morgan’s Emerging Markets Bond Index Plus. A “neutral” investment position for an investor would therefore have seen it with one-seventh of its emerging markets portfolio in Russia. As The Economist pointed out, “This is a result of the perverse logic of bond indices. A country that has issued a lot of debt will be weighted heavily in the index, even though it may be borrowing its way into trouble”.[147]

The remarkable capital drain that followed Russia’s actions, exposed the continuing immaturity of the market as fund managers once again showed no significant ability to discriminate between emerging economies that had been successfully reformed and those which had not.[148]

The response to East Asia’s financial troubles and Russia’s devaluation and moratorium also highlights the extent to which the increased globalisation of financial markets has exposed the emerging markets to sudden and severe reversals in capital flows.[149]

Coming hard on the heels of Russia’s crisis, this collapse further rocked the market.[150] The collapse was caused principally by the hedge fund taking a huge position on the assumption that the already very wide spreads on emerging markets debt and high-yield bonds would return to their more customary levels. The fund went short US Treasury’s and long emerging markets bonds, high-yield bonds and European government bonds. As we have seen, the turmoil in Russia caused a flood of capital into US Treasuries and out of the emerging markets sector. Similar outflows from high-yield and European government bonds meant that the hedge fund got squeezed so hard its capital ran out.

The rescue package coordinated by the U.S. Federal Reserve required an effective $3.5 billion buyout of the fund by a consortium of banks and brokers.[151] For the hedge funds’ principal financiers, this was apparently a cheaper option than allowing it to fail.

The most significant event for the market in 1999 was Brazil allowing its currency, the real, to float in January.

Brazil’s Devaluation

Much like a fine wine, Brazil’s troubles had been a long time fermenting.[152] In November 1997 in the sell-off which followed East Asia’s troubles, Brazilian debt performed the worst of the major debtors, with the spread on its bonds widening by 453 basis points as against 405 basis points for Argentina and 262 for Mexico.[153] In the first half of September 1998 an extraordinary $14 billion departed the country’s foreign exchange market. The central bank lifted the basic lending rate to 49.75 percent on September 10, just one week after lifting it to 29.75 percent, and spent its foreign exchange reserves heavily to defend the value of the real.[154] In November, Brazil and the IMF reached agreement on $41 billion in aid to bolster the nation’s finances.[155] This package was specifically aimed at heading off a devaluation due to the fear such a prospect engendered in the wake of Russia’s troubles.

The real had been kept overvalued to combat inflation and to continue compliance with the real plan which called for a slow depreciation of the real of between 0.58 and 0.68 percent per month. The real had been introduced in 1994 and the real plan had succeeded in defeating the ruinous hyperinflation which had previously dogged Brazil.[156] The considerable commitment of politicians to it was therefore understandable.

However, by January 1999, Brazil could no longer afford to defend its currency: it had used over one-half of its foreign exchange reserves doing so in the previous six months and two weeks earlier one of its largest states had decided to withhold payments on debt to the Brazilian government. On January 15, the government let the currency float and it fell in value 17 percent against the US dollar in a week and about one-third in the first quarter of 1999.[157]

The fallout from Brazil’s devaluation was nothing like as severe as that from Russia’s devaluation and moratorium only five months earlier.[158] Argentine and Mexican assets suffered but not to the extent that many had feared.[159] Given that Brazilian debt has historically been the lynch pin of the secondary market, the reasons for this limited fallout are illuminating:

1. In light of the Russian debacle, investors had (a) reduced their exposure to emerging markets in general and to Brazil in particular as it had been showing signs of trouble since October 1997, and (b) reduced their leverage so that losses in Brazil did not force consequential asset sales to the same extent as in August.[160]

2. The central participants in Brazilian debt were the major international banks which had far deeper and more diversified portfolios than the hedge funds which had dominated investment into Russia.[161]

3. The moral hazard of an expected bail-out did not influence the market in Brazil. A $41.5 billion financial package had been put in place by the IMF in late 1998 and investors were adjusting their portfolios uninfluenced by the prospect of any further rescues. Indeed, Brazil’s abandonment of the Real had to some extent been anticipated.[162]

4. Floating the currency was welcomed by many in the financial markets which believed the real to be overvalued. In the words of Arturo Porzecanski, “This is what we’d been hoping for. The government had the courage to let the currency find its own level.”[163]

Encouragingly, after Brazil’s devaluation investors quickly differentiated between Latin American countries with sound economic fundamentals such as Argentina, Mexico, and Chile and those without, such as Brazil itself, Ecuador and Venezuela.[164] The lack of strong contagion across the region speaks to the increasing sophistication and maturity of the market. Indeed, if one could somehow ignore the sheer panic that Russia’s devaluation engendered, and simply focus upon the secondary market’s reaction to East Asia’s woes in 1997 and Brazil’s in 1999, one might well conclude that the market was approaching maturity. Pity about the fallout from Russia in which the market relapsed into its old bad habits of “looking at all ‘emerging markets’ from Santiago to Seoul through a single lens”.[165]

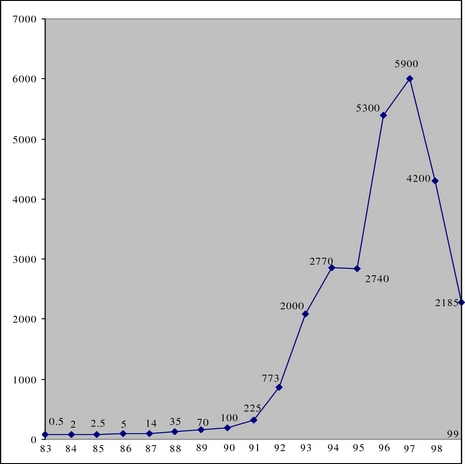

This period begins with the market coming out of the most rapid growth spurt in its history. Reported turnover for 1994 was $2.77 trillion face value of debt, an increase of some 40% over 1993 and nearly four times 1992 turnover. The brakes came on hard in 1995, with turnover stalled at $2.74 trillion. Rapid growth returned in 1996 with turnover nearly doubling to $5.3 trillion, and then rising slowly to $5.9 trillion in 1997. In 1998 the Asian and Russian crises asserted themselves and turnover fell some 29 percent to $4.2 trillion. In 1999 turnover was 2.185 trillion.[166] This turnover history is represented graphically as follows.

Figure Two[167]

Emerging markets debt represents a small part of the world’s capital markets. In September 1998, the capitalisation of JP Morgan’s Emerging Markets Bond Index (“EMBI”), the market standard, was $ 71 billion. The EMBI covers only U.S. dollar-denominated Brady bonds, and not the non-Brady bonds, local currency instruments and loans which comprise the balance of this market. Nonetheless, the total capitalisation of the emerging markets debt market would, on this basis, be about 2.2 trillion dollars[168] .

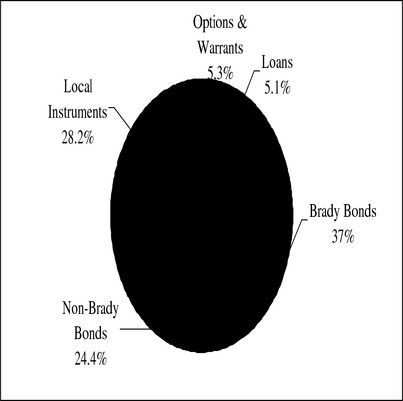

The market in this period traded five principal types of assets: Brady bonds, newly issued (non-Brady) bonds, local instruments, derivatives and loans. Local instruments are bonds denominated in either dollars or local currency, but issued in the local market, not internationally. The respective turnover of these types of assets in 1997 and 1998 is set forth below:

Table One – Turnover of Various Types of Emerging Markets Debt

Asset Type 1997 Turnover[169] 1998 Turnover[170] (Face Amounts in Billions of US $)

Brady Bonds 2,403 1,541

Non-Brady Bonds[171] 1,335 1,021

Local Instruments[172] 1,506 1,176

Debt Options and Warrants 365 233

Loans 305 213

The secondary market began its life as a swap market for loans, as virtually all the debt of the debt crisis of 1982 took the form of syndicated loans. As the market matured, swaps gave way to sales but loans remained the dominant form of debt throughout the 1980s.[173] The succession of Brady-style restructurings in the early 1990s saw many of these loans converted into Brady bonds: typically 30-year bonds with their principal and 12-18 months of interest payments collateralised by U.S. Treasury zero-coupon bonds.[174] Trading in Brady bonds in 1994 was up by 65% over 1993 and nearly seven times the turnover of loans.[175] The secondary market was, in essence now, a bond market, with Bradys representing 61% of market turnover. The transformation of what had begun as a loan market was by 1994 effectively complete with loans representing only 31 percent of turnover in 1999.

In early 1996 an enduring anomaly was removed as the ratings agencies removed the ratings distinction between a nation’s Brady bonds and Eurobonds. Eurobonds were newly issued bonds that did not arise from a restructuring of earlier indebtedness. Formerly, the agencies had rated Brady bonds one half a grade lower than Eurobonds arguing that debtors may turn to the holders of Brady bonds for relief in times of trouble more readily than to Eurobond holders as Bradys were the by-product of the bank loans of the 1980s. However, this prospect was determined to have diminished with the substantial sales of Brady bonds in the secondary market.[176] This begs the question why the yields of Bradys and Eurobonds did not also equalise, but they did not.

For a while the gap between the yield on newly issued bonds and the stripped yield on Brady bonds did narrow dramatically, from some 470 basis points in early 1996 to around 70 basis points in January 1998[177] - partly on the back of a wave of cross-over investment by investors who had concluded the risk on the two types of assets was essentially the same.[178] However, the gap soon widened again and by early July 1999 was around 420 basis points for the major debtors.[179]

Some argue these yield differences reflect a real credit distinction, i.e. that in troubled times debtors will honour their newly issued bonds more readily than their Brady bonds. This may have been true when the stock of global and euro bonds was so small that default on a nation’s Bradys and continued servicing of its global and euro bonds was a real possibility, just as most debtors did not reschedule their bonds in the 1980s because the stock of bonds was so small relative to loans. However, today the majority of bond debt of most of the major debtors is in the form of newly issued bonds, not Bradys, so defaulting on the latter while servicing the former would make no economic sense.[180] Potential reasons for this discrepancy in yields are as follows:[181]

(i) Stripping out the collateral, while easy to do on paper, is complex and difficult in practice and investors therefore are usually earning the blended yield which is lower than the yield on the global and euro bonds (because the yield on the collateral in the Bradys – US Treasury zero coupon bonds – is very low).

(ii) Brady bonds exhibit more secondary market volatility than global and euro bonds and so need to offer a higher return to investors.

(iii) Bradys tend to trade poorly in hard times as no bank is as committed to making two-way markets in them in the way that the arrangers of the global and euro bonds are committed to these issues.

With hindsight, 1994 represented the pinnacle for Brady bonds in this market. From accounting for 61 percent of turnover in 1994, the relative share of Brady bonds declined to 58 percent in 1995, 51 percent in 1996, 41 percent in 1997, 37 percent in 1998 and 31 percent in 1999, and by 2004 the proportion of turnover Brady bonds represented had fallen further to 6%.[182]

In each year from 1994 to 1999 Brazil’s was the most commonly traded debt, although by 1999 Mexico’s debt was also highly traded.[183] Brazilian debt accounted for 30 percent of turnover in 1997. In 1997 Argentine and Mexican assets filled the second and third spots with 21 and 17 percent of turnover, respectively. Fourth place went to Russian debt in 1997, displacing Venezuelan debt from 1996. 1998 saw Russian debt climb even further to second place with nearly 29 percent of turnover.[184] This capped five years of tremendous growth in Russian debt trading as Russian loans had represented only 1 1/4 percent of turnover in 1993. In 1999 the wheel turned full circle and Russian debt fall dramatically to represent only 5% percent of turnover.[185]

As can be seen, trading was concentrated in the debt of a small number of debtors throughout this period. Trading in the debt of Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Russia and Venezuela represented over 90 percent of turnover in 1996, 85 percent in 1997 and 81 percent in 1998. Asian assets represented only 3 percent of turnover in 1996, 2 percent in 1997, and 4 percent in 1998 (although EMTA notes that, for a variety of reasons, Asian trading is under represented in its surveys).

Substantial increases in turnover came in local instruments in this period. The external trading of local instruments accounted for 19 percent of turnover in 1994 and rose steadily to 28 percent in 1998, and 33 percent in the first quarter of 1999. Local-currency denominated instruments outnumbered US dollar-denominated instruments by five to one in 1997 and seven to one in 1998. The importance of local instruments is exemplified by the fact that in 1998 trading in one local instrument, Mexican Cetes, at $164 billion, far surpassed trading in all of Mexico’s Brady bonds, at $96 billion.[186]

Another area of dramatic increase in this period was non-Brady bond trading, reflecting the dramatic increase in new issues in 1996 and 1997. These bonds, principally Eurobonds and global bonds, accounted for 29 percent of turnover in 1999, up from 24 percent of turnover in 1998, 11 percent in 1996 and 8 percent in 1995.[187]

The downturn in 1998 can be attributed to the meltdown in the Russian economy in August of that year and the continued uncertainty as to whether Brazil’s economy would be pulled into the maelstrom of the Asian and Russian economic crises.

The best way to appreciate the relative turnover of the various emerging markets instruments is graphically, as follows:

Figure Three: Turnover of Emerging Markets Debt, by Instrument, 1998[188]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before 1993, pricing an option in this market was principally a matter of ascertaining the level at which the seller was prepared to sell the debt,[189] and while pricing strategies increased dramatically in sophistication, derivatives continued to be used, in the main, by investors wishing to place a directional bet on the market.[190] Using options for this purpose became expensive in 1994 and 1995 as the cost of derivatives to investors is determined by the volatility of the underlying instrument and the market shocks of 1994 and 1995 caused sharp rises in volatility.[191] The increases in the cost of options caused investors to begin to use spread plays such as a bull spread which is the purchase of a call at one strike price and the sale of a call at a higher strike price which achieves some of the purposes of a straight option for less cost.[192]

The range of debt upon which derivatives could be acquired expanded in this period to embrace the likes of Venezuela, Poland, Morocco, Nigeria, Russia, Ecuador and Peru along with the major debtors.[193] Nonetheless the derivatives on offer remained simple relative to the sophistication of more mature markets with options and warrants dominating the market.

The market in derivatives on the currencies of these debtors was far more sophisticated and developed. In 1995 the Chicago Mercantile Exchange launched trading in Mexican peso futures and options and created a new division, the Growth and Emerging Markets division, to trade initially futures and options on Emerging Markets’ currencies, equities, interest rates and stock market indices.[194]

Derivatives specific to this market include those designed to strip out the zero coupon bond component of Brady bonds and sell the pure risk to investors. This was typically achieved by going short the zero but was difficult to do for most Brady bonds because the zero coupon bonds, issued specifically by the U.S. Treasury for the purpose, contained covenants designed to prevent this. Such derivatives were easy to structure for Brazilian Bradys, the zero coupon bonds for which Brazil had bought on the open market,[195] and derivatives specialists found ways to do it for the Bradys of Nigeria and Bulgaria, among others.[196]

In Chicago, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) and the Chicago Board of Trade (CBoT) actively developed their emerging markets derivatives business. The CME offered futures on, among other things, individual types of Brady bonds and emerging markets currencies and the CBoT offers futures and options on a Brady Bond index and various local stock market indices. Such derivatives trading is also conducted on exchanges in the emerging market nations, particularly Brazil and Mexico.

There is evidence to suggest that the availability and use of derivatives may have exacerbated the Asian and Russian crises.

In Asia, swaps were popular in which banks paid the return on U.S. instruments and received the return on domestic instruments. These swaps were off-balance-sheet transactions that could be funded on limited margins. The swaps were very profitable for as long as the relevant exchange rate held firm and resulted in huge losses once the local currencies depreciated dramatically.[197]

In Russia, the debt moratorium resulted in massive losses for foreign and local users of over-the-counter derivatives – losses which were as high as $90 billion on some estimates.[198] The attractiveness of Russian state short-term obligations (GKOs) to investors was enhanced by the use of forward contracts to hedge the investors’ rouble exposures. However, forward currency hedges do not protect against debt moratoria. In the World Bank’s words, “It is unlikely that investors would have assumed the same level of exposure to GKOs if derivatives had not been available.”[199]

Other characteristics of the market in this period were (i) extreme volatility, (ii) equity-like characteristics, and (iii) the high degree of correlation between geographic regions. The volatility came from the long term of the Brady bonds and the political and economic uncertainty in the debtor nations and was ensured by the short-term investment horizon of the principal types of investors in Brady bonds: trading houses taking large positions, highly leveraged hedge and Latin capital-flight funds and open-ended mutual funds concerned about redemptions.[200] The equity-like nature of these debt instruments and the correlation between regions takes a little more explaining.

Two pieces of research highlighted the equity-like nature of emerging markets debt in this period. The first was by Gary Evans and Jose Cerritelli,[201] and the second by Michael Pettis and Jared Gross.[202] Each argued that Brady bonds and emerging markets loans more often behave like equities than like traditional debt instruments. The preconditions for this behaviour were laid by the institutional structure of the market, the large issue size, long maturity and high liquidity of Brady bonds, and the political and economic uncertainty of the debtor nations.[203] Market behaviour certainly supports this thesis: (i) investors in emerging markets debt in bull runs received equity-like returns well in excess of equities in developed nations and often in excess of emerging markets equities;[204] (ii) the volatility of emerging markets debt, particularly upon developments in the debtor’s economy, resembled that of equity rather than debt; and (iii) investors used Brady bonds “as a macroeconomic equity play” on the debtor nations,[205] i.e., investors wishing to express a view on a nation’s prospects did so by buying or selling Brady bonds.[206]

The degree of correlation between various emerging equity markets was historically thought to be low. As King and Cox wrote, in 1995, “[a] familiar argument for investing in the 24 or so emerging markets has been that they are basically uncorrelated with each other, and so have comparatively low volatility as a global portfolio.”[207] In their article, King and Cox challenged this assumption for equities and proved correlation was increasing within regions such as Asia or Latin America and even between regions.[208]

Whatever may have been the historical position in equity markets,[209] emerging markets debt has always been highly correlated both within and between regions. In 1995 most investors viewed all of Latin America as a single market, and many viewed the entire emerging markets as one,[210] as the tequila effect established conclusively,[211] and the contagion which followed the economic crises in Asia in 1997 and Russia in 1998 confirmed. The 1997 contagion was less severe than in 1995, which suggested maturation in the market that the contagion from Russia’s crisis was to deny.

Much light can be shed upon the market by considering the factors which have driven it. The principal factors driving the market in this period were: (i) the increasing role of cross-over investors caused principally by the low yields available in developed countries coupled to stronger economic fundamentals in many emerging nations, (ii) the strong growth in new issues, (iii) the buy-backs of Brady bonds, and (iv) the tremendous increase in foreign investment in local instruments. In addition to these factors, the new Brady-style restructurings provided substantial impetus to the market early in the period.[212] Each factor will be considered.

Cross-over is the market’s term for mainstream institutional investors which add emerging market bonds to their portfolios for higher yield. They include pension funds, insurance companies, high-yield (junk bond) mutual funds, high-grade bond funds, international bond funds and hedge funds.[213] These funds control such vast amounts of capital that five percent of their portfolios far exceed the capitalisation of the specialist emerging markets funds -- and many allocate that proportion to the emerging markets.[214] The cross-over phenomenon is, in essence, the story of a broad array of money managers becoming comfortable with higher risk investments and learning to leaven their portfolio with a small proportion of higher risk assets in the quest for a higher overall return.[215]

The unprecedented inflows to mutual funds in the early-to-mid-1990s shrivelled fixed income yields in the developed countries. Cross-over investors moved further afield in search of higher yields.[216] They began to invest substantially in emerging markets bonds in the bull run of 1993 but fled the market when the bears growled in 1994 and 1995. They returned in far greater numbers in the bull run of 1996 and provided much of the impetus for the dramatic 39 percent increase in debt prices that year.[217] The returns were certainly there: in the first eight months of 1996 U.S. Treasuries returned negative 2.8 percent; U.S. corporate bonds, 0.6 percent; U.S. junk bonds, 6.3 percent; and emerging markets bonds, 15.7 percent. Cross-over investors also acquired much of the record $90 billion of new bond issues that year -- indeed, as 1996 progressed more and more underwriters began to sell new emerging markets issues from their high yield or high grade desks, rather than emerging markets desks, in recognition of the destination of the majority of the bonds.[218]

The flood of cross-over investment caused the yields on the traditional emerging market instruments, Brady and euro bonds, to fall sharply. The emerging market money that had brought these bonds to prominence moved on in search of higher yield, this time to local instruments - bonds denominated in either dollars or local currency, but issued in the local market, not internationally.[219] Local instruments developed into a major secondary market sector in this period.

By 1997, many cross-over investors had come to depend on the emerging markets to maintain above-average returns. The initial test of their commitment to the markets came in April 1997 as U.S. short-term interest rates began to climb. The prospect of a mass withdrawal by cross-over investors, as in 1994, led to a decidedly jittery market. Cross-over investors are traditionally strong on analysis of the issuers’ business and balance sheet and less so on analysis of country risk. However, in 1997 they displayed maturity and understanding of the market and did not withdraw en masse.[220] Indeed, cross-over investors underpinned the market until late 1997 as pension funds and insurance companies began to allocate from 3 to 6 percent of their portfolios to the emerging markets and follow the lead of the mutual funds which often were more heavily committed to emerging markets.[221]

With their perceived higher creditworthiness, East Asian and Eastern European issuers appealed in particular to cross-over investors.[222] Indeed, the flow of capital allowed yields to decline so dramatically that new issues by these issuers at around 100 basis points over U.S. Treasuries became common and Slovenia was able to issue a $325 million five-year eurobond at only 58 basis points over U.S. Treasuries[223] in an issue sold principally to mainstream institutional investors. Likewise, Indonesia was able to issue $400 million in ten-year Yankee bonds priced at 100 basis points over Treasuries.[224] As subsequent events confirmed, investors were severely underestimating the country risk.[225]

Cross-over investors brought the emerging markets into the investment mainstream. The most remarkable change in this period is that the secondary market moved from a specialist niche market to one simply one sector, albeit a risky sector, of the mainstream market.[226] This was borne out by the behaviour of the cross-over investors in the depths of the October 1997 sell-off. While many left the market, many more stayed, and cross-over investors displayed far more commitment to the sector than, for instance, did the hedge funds.[227]

In 1998, cross-over investors were again consistent buyers of the new issues.[228] However, not even the new-found commitment of the cross-over investors could withstand the contagion from the Russian crisis and many withdrew from participation in the market having suffered egregious losses. One factor which undermined the commitment of cross-over investors to the market was that most institutional investors did not benchmark their emerging markets bonds against an index as they would investment grade bonds.[229]

While this research does not deal in depth with new issues - neither eurobonds, yankee, samurai or dragon bonds[230] - the influence of the new issues on the market in this period is too large to ignore entirely. Yen and Deutsche mark denominated bond issues were the saviours of Latin American and Eastern European sovereigns in 1995 when nearly one-half of all emerging markets debt issues were denominated in one of these currencies.[231] Yields on Deutsche mark and yen bonds were very low and non-investment grade paper was rare in these markets. This allowed Latin American borrowers to raise massive amounts of funds at relatively fine prices.[232]

With the bull run of 1996, the issuers returned to the U.S. dollar, with 69 percent of bonds dollar-denominated,[233] and to issuing in record amounts: over $90 billion of bonds issued compared to $56 billion in 1995.[234] The largest issuers were Mexico with $17.8 billion of bonds issued, South Korea ($14.9 billion), Argentina ($11.7 billion), Brazil ($9.1 billion) and Indonesia ($4.8 billion).[235] Through 1996 and up to October 1997, tenors increased significantly and spreads narrowed dramatically.[236]

Mexico’s return to the voluntary capital markets on this scale signalled an astonishing rehabilitation from the peso crisis and tequila effect. Mexico’s officials received effusive and universal praise in the international capital markets for engineering Mexico’s return to pre-eminence among emerging markets borrowers.[237] As Tulio Vera said in mid-1996, “That an issuer, which less than a year and a half ago could conceivably default, can now go out and raise a 30-year bond is incredible”.[238]

There were a number of notable issues in 1996. Foremost among them was Mexico’s massive $6 billion debt issue in July which was used to repay the relatively expensive loans advanced by the U.S. Treasury as part of the U.S.-led bailout of Mexico in 1995.[239] JP Morgan managed the issue and creatively supported its credit with future Mexican oil revenues and by structuring it as a hybrid transaction in which purchasers could acquire either floating rate notes or certificated bank notes. The issue thus appealed to both bond investors and commercial banks.[240] Mexico had laid the groundwork for this issue with an innovative $1.5 billion issue in November, 1995 which yielded the higher of 12-month dollar Libor or 28-day Cetes yields minus 6 percent - Cetes are local market peso-denominated paper. This allowed investors to take a punt on receiving high returns while minimising risk for those funding in Libor.[241]

In 1997 notable issues included Argentina’s issue of ten-year eurobonds denominated in pesos. Priced at only 160 basis points over Argentina’s dollar-denominated eurobonds and issued in an amount of 500 million pesos, the issue confirmed the market’s faith in Argentina’s fixed peg of the peso to the U.S. dollar,[242] a faith that was to prove utterly misplaced.[243] The fluidity of these markets was well demonstrated by Mexico - it made a number of bond issues in the first half of the year in yen, lira, pounds sterling and dollars, and in August, 1997 used the proceeds to prepay the $6 billion 1996 issue thereby lengthening its debt maturity profile, securing lower interest rates and freeing up the oil revenue collateral attached to the earlier bond.[244] 1997 was also notable for the regular issuances by Latin American issuers in a broad range of European currencies and for regular global bond issuances of $1 billion and upwards, designed to ensure the liquidity which had often been lacking in the new issue market.[245]

The dramatic growth in new issues of 1996 was sustained through the setbacks of 1997 such as the U.S. Federal Reserve’s increase in interest rates in the first quarter and the onset of East Asia’s troubles in June.[246] The primary market displayed a depth and stability not seen before. The debtor nations, with Brady bond exchanges, global bonds, local debt programs and increased European currency issuance, likewise displayed a more sophisticated and flexible approach to liability management than in earlier years.[247] The growth in new issues in this period was supported by the improving economic outlook and liability management of debtor nations and driven by the low rates of return on investments in industrial countries, the increased liquidity in international capital markets and the increasing tolerance of risk displayed by traditionally conservative institutional investors.[248] October 1997 changed all this -- the demand for emerging markets debt largely evaporated but, fortunately, most emerging markets borrowers had all ready raised all the capital they needed for the year. The demand for dollar-denominated debt was the slowest in returning. For instance, in the first two months of 1998, Argentina raised the equivalent of $1.35 billion in the Deutschemark, euro/Ecu, French franc, guilder and lira markets, and only $500 million in dollars.[249] In early 1998, the Latin sovereigns principally raised capital in a host of European currencies[250] and Latin blue-chip corporates and major banks issued short-term dollar denominated paper.[251]

Notwithstanding its very real economic problems, Korea’s $4 billion global bond issue in early April, 1998 was three-times oversubscribed. The IMF’s record $57 billion bailout was in place, but such strong appetite for bonds yielding only around 350 basis points over comparable U.S. Treasuries was difficult to fathom.[252]

Russia’s crisis in August closed the market to new issues for a while and, recovery, when it came, was slow. For instance, 23 debt deals were completed in the primary market in November and the first half of December 1998 compared to 65 in the same period in 1997.[253] In the aftermath of Russia, most investors required extra inducements to buy bonds. So, for instance, Argentina was able to raise $1 billion in November, 1998 by issuing bonds with warrants that permitted holders to buy Argentina’s global bond due 2027 in one years time, at a fixed price.[254] The other popular inducement, along with warrants, was predictably the securitisation of assets such as oil and telecom revenues. The trend to sweeteners continued well into 1999 – for instance, in February Mexico’s $ 1 billion bond issue included warrants entitling the exchange in one year of Brady bonds into new global bonds,[255] and Argentina’s similar issue included warrants entitling the purchase of more of the same bonds in one year.[256] Inducements were necessary in 1999 for debt of maturities of five years and longer.[257]

The development in new issues in this period with potentially the greatest significance for the future was the trend towards issuance in emerging market currencies by the corporations and sovereigns of the respective countries and by the supranational institutions.[258] The supranationals followed this route partly because very fine pricing was achievable in these currencies in this period, and partly to develop the Euromarkets for currencies such as the Czech and Slovak korunas, Korean won, Mexican peso, New Taiwan dollar, Philippine peso, Polish zloty and South African rand.[259] The supranationals issued $4 billion equivalent in emerging markets currencies in the first nine months of 1997, four times the figure for the whole of 1996 and nearly eight times the amount issued in 1995.[260]

The trend towards local currency issuance in the Euromarket was significant, because it offered the best way to shift the exchange rate liability from debtors and onto foreign investors and thereby minimise the prospects of, and pain for debtors and creditors of, any future sovereign debt crisis.[261] When emerging markets debtors borrow in their own currency and their economy is healthy the real cost of such borrowing tends to be high, as interest rates are generally higher on local currency debt. When their economy is going badly the real cost of the borrowing tends to be low due to a deteriorating exchange rate. Raising capital in the relevant local currency tends to ensure that the debtors pay heavily when they can afford to, and less when they cannot. This is precisely the sort of liability profile to avert, or minimise the damage to all parties from, a debt crisis.[262] If the day arrives when a majority of sovereign borrowing by emerging markets countries is denominated in the currency of the debtor, the international financial system will be inherently far more stable and the risks of international debt raising will be apportioned far more equitably between creditors and debtors than was the case in 1982, 1995, 1997 or 1998.

The premise underlying the massive loans of the 1970s was that sovereigns never go bankrupt because they can always raise taxes; i.e. that the loans arranged by the economic elite of a nation can always be repaid by its poor. It required seven years of suffering by the poor of Latin America before the developed world began to embrace the notion of debt relief. Borrowing in local currency would reward creditors more highly when times are good, and have debt relief already built in, when times are bad.

Brady Bond exchanges are, of course, a type of buy-back and have been considered above.[263] They provided some impetus to the market in this period. Far greater impetus was provided by informal debt buy-backs which are an altogether quieter affair than exchanges. In an informal buy-back a sovereign repurchases its Brady bonds on the secondary market, typically using the proceeds of newly issued bonds. These repurchases are often conducted anonymously through agents so information on these buy-backs is scarce. The rationale for the buy-backs is as for the exchanges: the total stock of debt is reduced because the Bradys are repurchased at a discount and the liberated collateral is used to retire further debt. The trade-off is that the newly issued bonds are usually issued at higher interest rates and for shorter terms than the debt being retired and, of course, the principal has to be repaid upon maturity – it is not covered by zero coupon bonds as with Bradys.

Depending upon secondary market prices, and prevailing interest rates, buy-backs can be an extremely attractive proposition for debtor governments.[264]

Brady bonds typically did not prohibit buy-backs and, as bonds, had none of the sharing, parri passu and other clauses typical of sovereign loan agreements and of which waivers are needed for buy-backs to proceed.[265] Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela reportedly conducted substantial buy-back programmes in 1995.[266] Indeed, most debtors bought back some of their debt when prices fell far enough, partly to profit from the large discount and partly to provide stability for their paper -- when Brady bond prices fell, their yields increased, which meant higher yields had to be paid to issue new Eurobonds,[267] and emerging markets sovereigns retained a healthy appetite for Eurobonds.

Peru, rather cheekily, bought back substantial amounts of its debt while engaged in negotiations with its bankers for a Brady-style restructuring.[268] Peru reportedly bought some of its debt in late 1994 and early 1995 through Swiss Bank Corporation at prices between 42 and 52 cents[269] and a further $1.2 billion of its debt in July and August, 1995 for $600 million.[270] This was highly beneficial for Peru as past due interest was not usually forgiven in Brady deals and Peru was so far in arrears that past due interest and principal were roughly equal at around $4 billion each.[271] However, past due interest ceased to matter upon the repurchase and retirement of debt, so Peru was twice as well off by repurchasing its debt in the market than by restructuring it in a Brady-style restructure, even one with a principal discount as high as 50 percent.

Later deals included Argentina’s repurchase of some of its Brady bonds with part of the $1.7 billion from two yen and Deutschemark Eurobond issues in late 1995,[272] Mexico’s repurchase of $1.2 billion of Brady bonds at 81 cents on the dollar with the proceeds of a $1 billion twenty-year bond in September, 1996[273] and its redemption of $1 billion of Aztec bonds in March 1997,[274] and Poland’s repurchase of some $1.7 billion of Bradys in May, 1997. Numerous other nations, particularly Brazil, took advantage of the low interest rates in the primary markets to issue new bonds and use the proceeds to repurchase Brady bonds quietly in the secondary market.[275] These buy-backs were an important source of impetus on the market in this period, while at the same time diminishing the stock of the most liquid instrument in the market.[276] By late 1997, Brady bonds represented only 12 percent of the total stock of emerging market debt, and yet remained the most actively traded portion of the market.[277]