University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 4 September 2008

Reflections on Criminal Justice Policy Since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody

Cunneen, C. (2007) ‘Reflections in Criminal Justice Policy since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody’, in Gillespie, N. (Ed) Reflections: 40 Years on from the 1967 Referendum, Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, Adelaide, no ISBN, pp, 135-146

Abstract

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was established in 1987 and reported to the Federal Parliament in 1991. It was generated by the activism from Aboriginal organisations including the Committee to Defend Black Rights and Aboriginal Legal Services, the families of those who had died in custody and their supporters. The Royal Commission provided a benchmark in the examination of Indigenous relations with the criminal justice system.

There is certainly strong evidence to suggest that the results of the Royal Commission have not been as expected. Despite the Royal Commission, Indigenous people remain dramatically over-represented in the criminal justice system. Deaths in custody still occur at unacceptably high levels and the recommendations of the Royal Commission are often ignored. Rather than a reform of the criminal justice system we have seen the development of more punitive approaches to law and order giving rise to expanding reliance on penal sanctions. Coupled with this greater reliance on penal sanctions, has been an inability to effectively generate a greater sense of obligation and responsibility among custodial authorities towards those who are incarcerated. The deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody is still as much of an issue today as it was two decades ago.

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCADIC) was established in 1987 and reported to the Federal Parliament in 1991. It was generated by the activism from Aboriginal organisations including the Committee to Defend Black Rights and Aboriginal Legal Services, the families of those who had died in custody and their supporters. The Royal Commission provided a benchmark in the examination of Indigenous relations with the criminal justice system.

The Commission found that the high number of Aboriginal deaths in custody was directly relative to the over-representation of Aboriginal people in custody. However, failure by custodial authorities to exercise a proper duty of care was also exposed by the Royal Commission. The Commission found that there was little understanding of the duty of care owed by custodial authorities and there were many system defects in relation to exercising care. There were many failures to exercise proper care. In some cases, the failure to offer proper care directly contributed to or caused the death in custody.

Commissioner Wootten in his report on New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania noted that ‘everyone of the (18) deaths was potentially avoidable and in a more enlightened and efficient system... might not have occurred. Many of those who died should not or need not have been in custody at all’ (Wootten, 1991: 7). He found that ‘negligence, lack of care, and/or breach of instructions on the part of custodial authorities was found to have played an important role in the circumstances leading to 13 of the 18 deaths investigated’ (Wootten, 1991: 63).

The Commission found that the most significant contributing factor to bringing Indigenous people into contact with the criminal justice system was their disadvantaged and unequal position within the wider society. The elimination of Indigenous disadvantage would only be achieved through empowerment, self-determination and reconciliation. The Royal Commission also found that in the 99 deaths in custody investigated, the Aboriginality of the person played a significant and in some cases dominant role in the reason for the person being in custody and dying in custody. In almost half of the cases the person had been removed from their families as a child, and a similar proportion had been arrested for a criminal offence before they were 15 years old. In over 80 per cent of cases the person was unemployed. In general, those who died had early and repeated contact with the criminal justice system (Johnston 1991).

The Royal Commission made 339 recommendations to achieve the ends of reducing custody levels, remedying social disadvantage and assuring self-determination. All Australian Governments committed themselves to implementing the majority of recommendations. The Royal Commission also made specific recommendations designed to reduce the occurrence of deaths in custody including the removal of hanging points from cells; increasing the awareness by custodial and medical staff of issues concerning the proper treatment of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous prisoners; and a greater commitment to cross cultural training for police, the judiciary and other criminal justice staff.

Contemporary Indigenous Deaths in Custody

There is certainly strong evidence to suggest that the results of the Royal Commission have not been as expected. Despite the Royal Commission, Indigenous people remain dramatically over-represented in the criminal justice system. Deaths in custody still occur at unacceptably high levels and the recommendations of the Royal Commission are often ignored. Rather than a reform of the criminal justice system we have seen the development of more punitive approaches to law and order giving rise to expanding reliance on penal sanctions. Coupled with this greater reliance on penal sanctions, has been an inability to effectively generate a greater sense of obligation and responsibility among custodial authorities towards those who are incarcerated.

In the mid 1990s a report prepared by the Office of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner (1996) examined 96 Indigenous deaths in custody during the period 1989-1996 and found that on average there were between eight and nine Royal Commission recommendations breached with each death. The findings of the report are particularly important in relation to health issues. In examining deaths in police custody, the report found there was a lack of proper assessment procedures and little involvement of medical personnel including Aboriginal Health Services. In deaths in prison, the report found that health services in some prisons were well below community standards, that ‘at risk’ information and medical information was not being exchanged between appropriate personnel, and that knowledge by medical staff and prison officers of cross-cultural health issues was poor (Office of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner 1996: xvii).

Of the 54 deaths in custody in 2005, some 28 per cent involved Indigenous detainees. Half of the Indigenous deaths occurred in police custody. Non-Indigenous deaths were more likely to occur while in prison (Joudo 2006). The Indigenous rate of death in prison is slightly lower than the non-Indigenous rate (1.2 compared to 1.4 per 1,000). The greater likelihood of Indigenous deaths occurring in police custody compared to non-Indigenous deaths reflects a consistent difference in location of Indigenous deaths in custody which has been noted since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (Johnston 1991).

An analysis of Indigenous deaths in custody since 2000 showed that many systemic defects in custodial situations which allow for deaths to occur relatively easily have not been remedied since the RCIADIC (Cunneen 2006). More generally the deaths illustrate the systemic disadvantage of Indigenous people which increases their contact with criminal justice agencies. The deaths show that negligence and lack of care are still endemic despite the accepted legal view that authorities have a duty of care for those in their custody. Indeed when an individual loses their liberty there is a heightened responsibility on the State to exercise a duty of care and prevent harm. Yet we see basic failings: hanging points remain common place, medical assessments and other vital information are not communicated or do not impact on decision-making, there is a lack of training in how to respond to vulnerable persons such as the mentally ill, and there is a failure to follow instructions or procedure. The deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody is still as much of an issue today as it was two decades ago.

Indigenous Young People and Juvenile Justice

Information on Indigenous young people held in police custody shows the extensive intervention by juvenile justice agencies into the lives of Indigenous youth. The last National Police Custody Survey in 2002 showed that 40 per cent of young people in police custody were Indigenous. The rate of custody per 100,000 of Indigenous young people was 1129 compared to a rate of 73.6 for non-Indigenous youth. The over-representation factor was 15.3 (Taylor and Bareja 2005:27). In other words, Indigenous young people are 15 times more likely to found in police custody than non-Indigenous youth.

Another way of seeing the extent to which Aboriginal youth are caught up in the juvenile justice system is through their level of over-representation in juvenile institutions.

Table 1

Indigenous Young People Aged 10-17 years in Detention

Centres in Australia

as at 30 June

2005

___________________________________________________________________________

State Indigenous

Non-Indigenous Indigenous Non-Indigenous

Or(2)

No No Rate(1) Rate(1)

___________________________________________________________________________

NSW 112 105 364.6 15.1 24.1

VIC 20 43 303.8 8.1 37.4

QLD 54 44 188.1 10.4 18.1

WA 79 27 555.3 12.6 44.1

SA 26 33 470.6 21.1 22.3

TAS 8 27 205.9 52.7 3.9

NT 15 2 136.6 13.8 9.9

ACT 3 7 352.9 20.4 17.3

Australia

317 288 312.3 13.6 23.0

___________________________________________________________________________

(1)

Rate per 100,000 of the respective juvenile populations

(2)

Over-representation measured by comparing rates per100,000.

Source: Adapted

from Taylor (2006:17-23).

On the 30th June 2005 there were 605 young people aged 10-17 in detention in Australia, of these 52.4 per cent (317) were Indigenous youth. Table 1 shows that majority of young people incarcerated in New South Wales, Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland are Indigenous. New South Wales has the greatest number of Indigenous young people in detention centres (112); the highest rate Indigenous youth incarceration is in Western Australia (555.3 per 100,000).

In every jurisdiction in Australia the rate of incarceration for Indigenous youth is much higher than the non-Indigenous rate. The level of over-representation is greatest in Western Australia where an Indigenous young person is 44 times more likely to be in a detention centre than a non-Indigenous youth. Nationally, Indigenous young people are 23 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-Indigenous youth. The problem of over-representation of Indigenous young people in the juvenile justice system has actually worsened over the last decade (Taylor 2006).

Some of the key criminal justice issues in relation to this over-representation of Indigenous young people include adverse policing, adverse use of discretion and the development of new ‘street cleaning’ legislation. There has been a growing tendency to provide police with powers to remove children from public places under certain circumstances, and to hold parents ‘responsible’ for the actions of their children. An example of this type of legislation is the New South Wales Children (Protection and Parental Responsibility) Act 1997. Analysis of the legislation shows that it impacts disproportionately on Indigenous youth (AJAC 1999a). The ‘Northbridge Curfew’ in Perth is an example of differential policing which negatively affects Indigenous youth. The Western Australian Law Reform Commission found that,

While ostensibly the Northbridge curfew applies to all children, statistics show that the majority of children dealt with pursuant to the curfew are Aboriginal. For example, 88 per cent of children dealt with by police in 2004 were Aboriginal (Law Reform Commission of Western Australia 2006:210).

The problem of differential policing of Indigenous young people can also be seen in the way search powers and move-on powers have been used. The New South Wales Crimes Legislation Amendment (Police and Public Safety) Act 1998 provides police with the power to search for prohibited implements (knives, scissors, etc.). Search powers and move-on powers for juveniles are used more frequently in Aboriginal communities (New South Wales Office of the Ombudsman 2000).

Adverse use of police discretion also negatively impacts on the likelihood of Indigenous young people having the advantage of diversionary options in place of appearing in court. While most Australian jurisdictions have alternatives such as police cautioning and youth justice conferencing, the evidence repeatedly shows that Indigenous young people are less to be cautioned and less likely to be referred to a conference than a non-Indigenous young offender (Cunneen and White 2007: 153-160). As a result they end up in court and subsequently with a criminal record.

Policing and Minor Offences

Many of the recommendations from the RCADIC dealt with diversion from police custody and this is not surprising given that two thirds of all the deaths which were investigated occurred in police custody rather than prison. Furthermore, most Aboriginal people at the time of the Royal Commission were in police custody for minor offences: in particular public drunkenness and street offences (Johnston 1991:(1)12-13). The focus of recommendations in this regard was to decriminalise public drunkenness, provide sobering-up shelters, change practice and procedures relating to arrest and bail (particularly for minor offences) and to provide alternatives to the use of police custody[1].

Despite the decriminalisation of public drunkenness in most jurisdictions, many Indigenous people still come into contact with the criminal justice system because of the public consumption of alcohol. These problems are related to the use of protective detention, the use of local council by-laws prohibiting alcohol consumption and other restrictions such as the Northern Territory’s law prohibiting alcohol consumption within two-kilometres of licensed premises, and penalties associated with breaches of Queensland’s alcohol management plans. Some alcohol restrictions only apply to Indigenous people or Indigenous communities (Race Discrimination Commissioner 1995; McRae et al 2003: 504-505; Cunneen 2005).

Public order offences and police powers to intervene in public places remain among the most contentious issues in the application of the criminal law and policing of Indigenous people. Minor offences are still cause for police intervention in relation to Indigenous people. A recent report from the Law Reform Commission of Western Australia noted the following:

There are numerous accounts to suggest that move-on notices are being issued to Aboriginal people in inappropriate circumstances and that Aboriginal people are being disproportionately affected by this law. It appears that in some cases Aboriginal people are being targeted by the police for congregating in large groups in public areas even though no one is doing anything wrong...

The Commission is very concerned about the apparent discriminatory treatment of Aboriginal people with respect to move-on notices... [B]ecause a move-on notice can be issued when a police officer reasonably suspects that the person is likely to commit an offence there is a large scope for misuse of police discretion (Law Reform Commission of Western Australia 2006:209).

Offensive language and offensive behaviour are offences under state and territory law in Australia. The RCADIC recommended that the use of offensive language in circumstances of interventions initiated by police should not normally be occasion for arrest and charge (Recommendation 86). A review of the implementation of this recommendation found that,

Throughout Australia, Aboriginal people are being arrested, placed in police custody and, in some cases, imprisoned on the basis of behaviour that the police find offensive and which has been precipitated by police actions (Cunneen and McDonald 1997:8).

In New South Wales the maximum penalty for offensive conduct in three months imprisonment and for offensive language a fine of $660. Aboriginal people are significantly over-represented in prosecutions for these types of offences. Research by the New South Wales AJAC found that in 1998 some 20 per cent of all prosecutions for these offences involved Aboriginal people, and 14.3 per cent of all Aboriginal people appearing in New South Wales Local Courts had at least one charge of offensive language or offensive conduct. In one out of four cases where an Aboriginal person was charged with offensive language or offensive conduct, they were also charged with offences against the police such as resist arrest or assault police (AJAC 1999b).

Some magistrates have questioned whether the use of the word ‘fuck’ in public constituted offensive language given its ubiquitous nature in social discourse. For example, New South Wales Magistrate Heilpern dismissed offensive language charges against an Aboriginal woman in Police v Butler [2003] NSWLC at 1 (Moruya Local Court) and against an 18 year old Aboriginal man in Police v Dunn (Unreported, 27 August 1999, Dubbo Local Court).

The Criminal Process: The Use of Arrest for Minor Offences

The RCADIC recommended that arrest should be used as a last resort when deciding to commence criminal proceedings (Recommendation 87). The use of arrest as a last resort was one of the keys to achieving a reduction in the over-representation of Indigenous people in police custody. The problem for Indigenous people is that police tend to use arrest for minor offences, and they tend to use it more frequently in their apprehension of Indigenous people than they do with non-Indigenous people. A recent report on the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement found that 52 per cent of Indigenous interventions involved the use of arrest compared to 36.5 per cent of non-Indigenous interventions. Conversely, more than half of non-Indigenous interventions were commenced by way of a ‘notice to appear’ (a type of summons) (Cunneen 2005: 43).

In a matter involving charges against an Aboriginal man for resisting arrest, assaulting police and intimidating police, Magistrate Heilpern ruled that evidence from police should be excluded because it had been obtained as a result of an improper act. The improper act in this case was the arrest of Lance Carr for offensive language in circumstances where the use of summons or court attendance notice would have been more appropriate. The Director of Public Prosecutions appealed the matter to the New South Wales Supreme Court, where the appeal was dismissed. Justice Smart noted that

This Court... has been emphasising for many years that it is inappropriate for powers of arrest to be used for minor offences where the defendant’s name and address are known, there is no risk of him departing and there is no reason to believe that a summons will not be effective. Arrest is an additional punishment involving deprivation of freedom and frequently ignominy and fear. The consequences of the employment of the power of arrest unnecessarily and inappropriately and instead of issuing a summons are often anger... and an escalation of the situation leading to the person resisting arrest and assaulting the police (Carr [2002] NSWSC 194 at 35).

However, it appears that in most cases the use of arrest rather than summons for prosecutions of minor offences goes unchallenged. One result of the use of arrest in these types of cases is that bail is imposed which in itself leads to an assortment of further problems and potential criminalisation.

Imprisonment

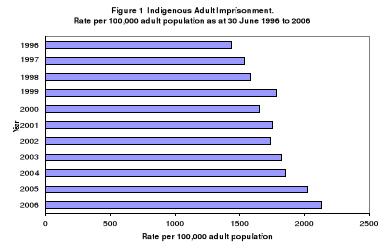

There is little cause for optimism when analysing the figures for Indigenous adult imprisonment. As shown in Figure 1, Indigenous imprisonment rates have grown steadily over recent years.

Source: Adapted from ABS (2006:33).

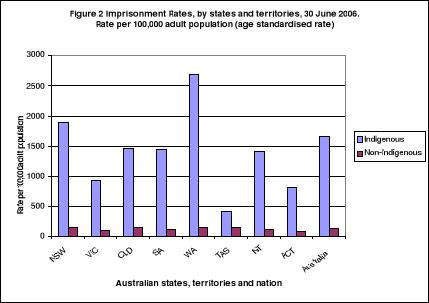

Source: Adapted from ABS (2006:33).

Current comparative data on Indigenous imprisonment is shown in Figure 2. Western Australia has the highest rate of Indigenous imprisonment in Australia at 2688 per 100,000 of the population. The non-Indigenous imprisonment rate in that state is 145 per 100,00. Thus Indigenous people are 18 times more likely than non-Indigenous people to be imprisoned in Western Australia. The over-representation rate of Indigenous people in Australia is 12.9.

There are many reasons for this over-representation. I want to

draw attention to two factors. The first is the failure to provide

an adequate

level of service for Indigenous people, particularly in the provision of

non-custodial sentencing options. The second

is the failure to properly

recognise and resource Indigenous criminal justice interventions.

The Lack of Programs and Services for Indigenous people

It has been widely noted that Indigenous people lack the same access as non-Indigenous people to the programs and services offered by the criminal justice system to both offenders and victims (See, for example, Cunneen 2005, Mahoney 2005, Morgan and Motteram 2004, Law Reform Commission of Western Australia 2006). These include the absence of or highly restricted availability of:

The Mahoney Inquiry into Offenders in Custody and in the Community in Western Australia found that there was a serious deficiency in Aboriginal-specific programs to reduce offending behaviour, and that the lack of appropriate programs for Indigenous offenders may partly explain higher recidivism rates. Lack of appropriate services means fewer opportunities for rehabilitation and more re-offending (Law Reform Commission of Western Australia 2006:85)

Similarly a review of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement in Queensland found Indigenous offenders are less represented on community corrections than they are in the prison population. One reason for this is the widely acknowledged difficulty of providing effective supervision for community corrections in remote communities. There was widespread concern among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander legal services and magistrates about the lack of sentencing alternatives in remote areas (Cunneen 2005). In New South Wales a recent parliamentary report also found that many sentencing options were not available in rural areas. In particular supervised bonds, community service orders, periodic detention and home detention were not available in many parts of the state (Legislation Council Standing Committee 2006:xii).

The Growth in Indigenous Justice Interventions

One of the most significant positive development in the post-RCADIC period has been the flourishing of Indigenous justice interventions. They facilitate the development of Indigenous self-determination in the criminal justice arena, and provide the opportunity to open a space in which Aboriginal law can function. The primary limitation at present is that these mechanisms operate, by and large, within the broader parameters of non-Indigenous state law, often with inadequate support and recognition.

The development of Aboriginal justice programs is perhaps better understood as the facilitation and development of ‘Aboriginal justice institutions’. This emphasises the important governance aspect of self determination, and stresses that modern Indigenous justice institutions are a process through which Aboriginal communities are empowered to apply their own laws and legal processes within a negotiated relationship to state legal institutions.

The New South Wales AJAC noted that

In recent years there have been a number of examples where local Indigenous communities have been allowed to have a direct decision making role in local justice administration and where justice processes have been adapted to incorporate local Indigenous views and needs.

These examples show that a greater flexibility in justice administration can allow for Aboriginal customary law to be recognised and provide a role for a local Aboriginal community and its culture to play. Further what we do know is that where this has been done, and local Indigenous communities have had a direct role in justice administration, where procedures and punishments are designed and delivered according to local culture and need, that the greatest impact on rates of offending/re-offending are achieved (Thomas 2003:9).

A similar argument has been made in relation to the potentially transformative process of Aboriginal courts:

[T]he task remains to ensure that the momentum of the Aboriginal courts transforms the relationships that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians both in the criminal justice system and also in the broader context of society itself. Failure to do so will perpetuate the cycle of over-representation of Aboriginal offenders in the nation’s gaols and will certainly spell the end of any dreams of reconciliation (Harris 2004:39).

Paul Chantrill has noted in relation to Aboriginal community justice groups in Queensland that ‘the achievement in these communities centre on increasing emphasis on community development strategies designed to improve opportunities for young people, the re-establishment of community authority and discipline based on the authority of community elders as well as efforts to improve the community’s relationship with external justice agencies’ (Chantrill 1998:163).

A wide range of Aboriginal justice institutions exist and can play an integral and practical role in providing a bridge between self-determination, governance and Aboriginal law on the one side and the non-Indigenous legal system on the other.

Aboriginal Courts

Aboriginal courts (Koori Courts, Murri Courts and Nunga Courts) have been established for both adult and juvenile offenders in Victoria, Queensland and South Australia over the last few years. The courts involve an Aboriginal Elder or justice officer sitting on the bench with a magistrate. The Elder can provide advice to the magistrate on the offender to be sentenced and about cultural and community issues. Offenders could receive customary punishments or community service orders as an alternative to prison. Aboriginal Courts may sit on a specific day designated to sentence Aboriginal offenders who have pled guilty to an offence. The Court setting may be different to the traditional sittings. The offender may have a relative present at the sitting, with the offender, his/her relative and the offender's lawyer sitting at the bar table. The magistrate may ask questions of the offender, the victim (if present) and members of the family and community in assisting with sentencing options (Harris 2004, Marchetti and Daly 2004).

Circle Sentencing

Circle sentencing, or circle courts, began in Canada

in early 1992. Circle courts are based on traditional Indigenous forms of

dispute

resolution and have been adopted by a number of more traditionally

oriented first nations people in Canada, but have subsequently

been adopted in

Canadian urban settings and are also now used in the United States and

Australia. Pilot circle sentencing began in

Nowra, New South Wales in February

2002 and the program has subsequently been expanded to other areas such as Dubbo

and Brewarrina.

The Nowra trial was evaluated by the NSW Aboriginal Justice

Advisory Council and the NSW Judicial Commission. The evaluation found,

inter

alia, that circle sentencing

Community Justice Groups

Different types of Aboriginal Justice Groups have been established in several jurisdictions. Perhaps the most successful and certainly best evaluated have been the Aboriginal Justice Groups in Queensland.

Evaluations of justice groups indicate they can

Aboriginal Community Justice Groups have been established in New South Wales, as have community justice forums. Aboriginal Community Justice Groups can work with police to issue cautions, establish diversionary options, support offenders, assist in access to bail, provide assistance to courts, and develop crime prevention plans.

Night patrols

One of the longest running community-controlled initiatives in Indigenous communities has been the ‘night patrol’. They are also one of the few types of initiatives that have been evaluated at a more systematic level. Generally the evaluations have been very positive.

Evaluations of night patrols indicate they can achieve

Recently, Blagg and Valuri (2004) identified over 100 self-policing initiatives operating in Aboriginal communities throughout Australia. They suggest that underpinning these initiatives is ‘a commitment to working through consensus and intervening in a culturally appropriate way to divert Indigenous people from a diversity of potential hazards and conflicts.

Taken together there exists at least in skeletal form the institutional processes for Indigenous justice which operates alongside the Anglo-Australian system. What we need to think about is opening the space for these initiatives to flourish into what Fitzgerald referred to in the Cape York Justice Study as ‘pods of justice’:

There needs to be institutional space or spaces created for the accommodation of Aboriginal law within the broader Australia legal system. There must be institutional design for the administration of a local order by Aboriginal communities. There must be ‘pods of justice’ distinct in form and function, autonomous but contributing to a federal whole. Authority must be devolved to Aboriginal communities so that they may first determine the law and order issues of their [own] (State of Queensland nd: 113).

Conclusion

As noted previously the RCADIC provided an important opportunity for changing the way the criminal justice system deals with Aboriginal people and for changing Aboriginal people’s position in a postcolonial Australia. This does not mean that the Royal Commission is beyond criticism, or that every recommendation it made should be uncritically implemented (Cunneen and McDonald 1997, Cunneen 2001). However, it does provide the starting point for any reasonable analysis of responding to Aboriginal deaths in custody, and reducing Aboriginal over-representation in custody. The long list of shocking cases provided a public understanding of the processes of racism in the criminal justice system and Australian society more generally. The stories of the deaths in custody were the incontrovertible stories of institutional racism, of human tragedy and monumental inhumanity. Some cases showed profound callousness, others simple indifference. The current tragedy is that so many of the circumstances leading to deaths in custody, and identified by the RCADIC, are still routine occurrences.

At the broadest level, the political conditions of the late 1990s and the new century have not been conducive in Australia to effective reform of the criminal justice system. There is little doubt that we have moved into a more punitive period in relation to criminal justice responses, and whatever impetus there was to reform in the early 1990s has largely evaporated. We see this drift into ‘law and order’ responses manifested in a range of areas including increased police powers, ‘zero tolerance’ style laws which increase the use of arrest for minor offences, greater levels of bail refusal and longer periods of imprisonment for a range of offences. However, on the positive side there has been a renaissance in Indigenous justice institutions. These provide the potential for significant change in the criminal justice system, and an opportunity for greater recognition of the aspirations of Indigenous people.

REFERENCES

Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council (AJAC), New South Wales, 1999a Report on the Children (Protection and Parental Responsibility) Act 1997, AJAC, Sydney.

Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council (AJAC), New South Wales, 1999b Policing Public Order, Offensive Language and Behaviour. The Impact on Aboriginal People, New South Wales Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council, Sydney.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2006 Prisoners in Australia. Catalogue No. 4517.0 Canberra: ABS.

Chantrill, P 1998 ‘Community Justice in Indigenous Communities in Queensland: Prospects for Keeping Young People Out of Detention’ Australia Indigenous Law Reporter, vol 3, no 2.

Blagg, H. and Valuri, G. 2004 ‘Self-Policing and Community Safety: The Work of Aboriginal Community Patrols in Australia’ Current Issues in Criminal Justice, vol 15, no 3.

Cunneen, C. and McDonald, D. 1997 Keeping Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people out of custody. Canberra: ATSIC.

Cunneen, C. and White, R. 2007 Juvenile Justice Youth and Crime in Australia, Melbourne: OUP.

Cunneen, C. 2001 ‘Assessing the Outcomes of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody’ Health Sociology Review, Vol 10, No 2, pp33-53

Cunneen, C. 2005 Evaluation of the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement, Institute of Criminology, University of Sydney, Sydney

Cunneen, C. 2006 ‘Aboriginal Deaths in Custody: A Continuing Systematic Abuse’, Social Justice vol 33, no 4.

Johnston, E., 1991 National report, 5 Vols, Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody Canberra: AGPS.

Joudo, J. 2006 Deaths in Custody in Australia. National Deaths in Custody Program. Annual Report 2005, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Harris, M 2004 ‘From Australian Courts to Aboriginal Courts in Australia- Bridging the Gap?’ Current Issues in Criminal Justice vol 16 no 1.

Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, 2006 Aboriginal Customary Laws, Final Report, Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Perth.

Legislation Council Standing Committee, 2006 Community Based Sentencing Options for Rural and Remote Areas and Disadvantaged Populations, Sydney: New South Wales Parliament.

Mahoney, D. 2005 Inquiry into the Management of Offenders in Custody and in the Community, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Perth.

Marchetti, E. and Daly, K. 2004 ‘Indigenous Courts and Justice Practices in Australia’ Trends and Issues No 277, Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

McRae, H., Nettheim, G., Beacroft, H. and McNamara, L. 2003 Indigenous Legal Issues, Thomson Law Book, Sydney.

Morgan, N. and Motteram, J. 2004 Aboriginal People and Justice Services: Plans, Programs and Delivery, Background Paper 7, Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Perth.

New South Wales Office of the Ombudsman, 2000 Police and Public Safety Act. Sydney: Office of the Ombudsman.

Office of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice

Commissioner

1996 Indigenous deaths in custody 1989-1996 Sydney:

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

Potas, I., Smart, J., Bignell, G., Lawrie R. and B. Thomas, 2003 Circle Sentencing in New South Wales. A Review and Evaluation, Sydney: New South Wales Judicial Commission and Aboriginal Justice Advisory Committee.

Race Discrimination Commissioner 1995 Alcohol Report, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney

State of Queensland, Cape York Justice Study, 5 Vols, <http://www.communities.qld.gov.au/community/publications/capeyork.html> .

Taylor, N. & Bareja, M. 2005 2002 National Police Custody Survey, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Taylor, N. 2006 Juveniles in Detention in Australia 1981-2005, Technical and Background Paper No 22, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Thomas, B. 2003 Strengthening Community Justice. Some Issues in the Recognition of A Customary Law in New South Wales, Sydney: New South Wales Aboriginal Justice Advisory Council.

Veld, M. and Taylor, N. 2005 Statistics On Juvenile Detention in Australia 1981 – 2004, Technical and Background Paper No 18. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Wootten, H. 1991 Regional report of inquiry in New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania, Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody. Canberra: AGPS.

[1]Changes to police practice and legislation to enhance diversion from police custody are called for in recommendations 60-61, 79-91 and 214-233 (Johnston 1991: vol 5).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2008/7.html