University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 10 March 2009

A Cultural Analysis of Administrative Justice

Simon Halliday[1]

Colin

Scott[2]

Citation

This paper is to be published as a chapter in an edited collection of essays: Adler, M (ed) Administrative Justice in Context, (Oxford: Hart Publishing, forthcoming, 2009).

Address for correspondence: simon.halliday@strath.ac.uk

Abstract

In recent years we have seen rapid change in the organisation of public management. Various developments, sometimes captured in the notion of the 'new public management', have significantly altered the character of public administration. This presents quite a challenge for theorists of administrative justice. The values and processes which infuse new public management sit in some tension with traditional conceptions of administrative justice, particularly within legal theory. To what extent should the concept be extended to embrace these real-world developments? Further, is there more to be said about administrative justice than is not captured by existing theory, even including a focus on new public management? These questions form the background to this article in which we develop a typology of administrative justice - an analytical framework which captures the variations in how 'administrative justice' might be conceived.

Our analysis re-works the typologies of Mashaw, Adler and Kagan and places them in a wider framework developed from grid-group cultural theory. The analysis also draws attention to conceptions of administrative justice not previously discussed in the literature: decision-making by lottery, and decision-making by consensus.

INTRODUCTION[3]

In recent years we have seen rapid change in the organisation of public management (see the chapters by Gamble and Thomas and by Clarke, McDermont and Newman in this volume). Various developments and innovations, sometimes captured in the notion of the ‘new public management’, have significantly altered the character of public administration. This presents quite a challenge for theorists of administrative justice. The values and processes which infuse new public management sit in some tension with traditional conceptions of administrative justice, particularly within legal theory. To what extent should the concept be extended to embrace these real-world developments? Would it stretch the notion of administrative justice too far to include within it the values associated with the market and consumerism? Would this rob the concept of its analytical purchase? Or, if the notion of administrative justice is to be so extended, how should we understand the relationship between traditional conceptions and newer conceptions? Is there any kind of logic or shared foundation which connects the old and the new? Further, is there more to be said about administrative justice that is not captured by existing theory, even including a focus on new public management?

These are important questions for the field. They form the background to this chapter in which we develop a typology of administrative justice – an analytical framework which captures the variations in how ‘administrative justice’ might be conceived. In developing typologies, of course, it is wise to recognise previous significant works in the field. We seek to build on such and provide further insights into them. In this vein, we position the contributions of Jerry Mashaw and Michael Adler, who have similarly developed typologies, as important and helpful examples of, respectively, a traditional legal theory of administrative justice and more recent theorising in light of the new public management. We also consider the contribution of Robert Kagan (in this volume) and its implications for understanding Mashaw. We ultimately situate these administrative justice theories within a broader analytical framework which has been derived from anthropology and been used to great effect in political science. We use grid-group cultural theory, developed initially by Mary Douglas (1982b), as the foundation for our ideal typology. Grid-group cultural theory, we suggest, is a particularly useful analytical framework for this endeavour. It promises two significant advances to the theory of administrative justice. First, it offers a richer understanding of the relationships between existing conceptions. Second, it reveals new conceptions of administrative justice which have not hitherto been discussed in the field. We will set out this in much greater detail in due course. First, however, we must examine what is meant by ‘administrative justice’ for the purposes of this chapter.

WHAT IS ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE?

Following Mashaw, we define administrative justice as “the qualities of a decision process that provide arguments for the acceptability of its decisions” (1983: 24). There are two related features of this deceptively simple definition worth stressing at the outset. First, Mashaw was not talking about any old decisions. His focus was on ‘implementing decisions’ (1983: 16) or ‘administrative adjudication’ (ibid: 23) by public bodies. His concern was with the organisation of decision-making systems within agencies which have been ‘charged with implementing the policies of the administrative-regulatory state’ as Kagan phrases it (in his chapter in this volume). To this end, Mashaw used the administration of social security disability law as his case study.

Second, Mashaw’s primary focus was on processes which produce decisions. It might seem trite to repeat this. However, our point here is that there are many features of an administrative system which, although relating to decision-making, do not actually constitute the decision-making process itself. Matters such as rights of redress or the regulation of public administration - broad issues of public accountability which precede, accompany, and follow decision-making processes – are, of course, interesting, important and worthy of enquiry. They are matters which could be (and are) meaningfully discussed under the umbrella of ‘administrative justice’. However they are not the direct concern of this chapter. Like Mashaw, our focus here is on the notion of justice as it relates to primary decision-making processes - what Kagan (in this volume) describes as ‘intra-agency scholarship’. As we will explain further below, it is important to keep this distinction clear in order to maintain the clarity of the cultural typology of administrative justice we develop.

As noted above, our primary reference points are, first, the celebrated typology constructed by Mashaw (1983) and, second, its subsequent development by Michael Adler (2003, 2006) within the context of UK public service delivery. Although this work is now very well known, for the purposes of our analysis it is summarised briefly below.

Mashaw’s Typology of Administrative Justice

From the critical literature about the administration of social security disability law, Mashaw (1983) detected three different perspectives on the appropriate goals of the administration. He believed that these diverse critiques reflected distinct conceptions or ‘models’ of administrative justice: (1) bureaucratic rationality, (2) professional treatment, and (3) moral judgment. These models of administrative justice, he suggested, were each attractive in their own right, but were highly competitive: “the internal logic of any one of them tends to drive the characteristics of the others from the field as it works itself out in concrete situations” (ibid: 23). So, on the ground, we may expect to see evidence of each model in action, though one will generally be dominant.

The bureaucratic rationality model is concerned with efficiency – the values of accuracy (targeting benefits to those eligible under the programme) and cost-effectiveness. In devising the programme, legislators or policy makers have decided who is eligible and who is not – it has made the value judgments about deservingness. The task of the administrative system is to implement those preferences on a grand scale in as accurate and consistent a way as possible, and with a concern for economy:

‘[t]he legitimating force of this conception flows both from its claim to correct implementation of otherwise legitimate social decisions and from its attempt to realize society’s pre-established goals in some particular substantive domain while conserving social resources for the pursuit of other valuable ends.’ (ibid: 26).

Discretionary judgments by individual officers are antithetical to the goals of accuracy and consistency. Instead, the administrative system must operate on the basis of clear rules and guidance which tell low-level officers how to process claims and which promote consistency of decision-making.

Professional treatment, by way of contrast, has at its heart the service of the client. Medicine is clearly the exemplar. The goal of the system is to meet the needs of the individual claimant. The administrative system is about matching available resources to claimants’ needs through the medium of professional and clinical judgment. Information about the claimant must be obtained, but accuracy is not a normative concern.

‘The professional combines the information of others with his or her own observations and experience to reach conclusions that are as much art as science. Moreover, judgment is always subject to revision as conditions change, as attempted therapy proves unsatisfactory or therapeutic successes emerge. The application of clinical judgment entails a relationship and may involve repeated instances of service-oriented decisionmaking... Justice lies in having the appropriate professional judgment applied to one’s particular situation in the context of a service relationship (emphasis in original)’. (ibid: 28-9).

Mashaw’s third model is that of moral judgment. This model derives from traditional notions of court-centred adjudication. The function of such adjudication is not just to resolve disputes about facts, but is also to decide between the competing interests of litigants – what Mashaw describes as “value defining” (ibid: 29). Issues such as reasonableness, deservingness and responsibility are not questions of fact, but rather are matters of judgment. Accordingly, litigants must be afforded administrative protections in the dispute so that they can have an equal opportunity to present their case, rebut allegations against them, and argue for their interests to be privileged. The adversarial element often cannot be transposed over to the context of administrative adjudication,[4] but in certain respects the claimant is nevertheless treated as if he/she is in dispute over a rights claim. The administrative system views the claimant as someone who has come to claim a right, and revolves around giving the claimant a fair opportunity to fully participate in the process of adjudicating whether the right exists or is to be denied: “[t]he important point is that the ‘justice’ of this model inheres in its promise of a full and equal opportunity to obtain one’s entitlements” (ibid: 31).

Adler’s Typology of Administrative Justice

Adler has been much influenced by the pluralistic approach of Mashaw – his recognition of the plurality of normative positions about the justice of decision processes and the fact that models of administrative justice have to compete with each other in the social reality of public administration (Adler 2006: 621). However, he saw the need to supplement and update Mashaw’s typology (2003, 2006). Adler uses the language of ‘ideal types’, rather than models, and adds three new models of administrative justice (Adler 2003). They are (1) managerialism, (2) consumerism, and (3) markets. Managerialism gives autonomy to public sector managers. Managers bear the responsibility for achieving prescribed standards of service in an efficient way and enjoy the freedom to manage their departments to this end. They are subject to systems of performance audit, and the administrative system revolves around publicly demonstrating the quality of administration according to defined performance indicators. Like Mashaw’s bureaucratic rationality model, the focus of this ideal type is on the administrative system as a whole, and only indirectly on the plight of individual citizens (who are presumed to benefit from the attainment of an efficient and well-performing system).

By way of contrast, the plight of the citizen is at the heart of Adler’s consumerism ideal type. Here, the administrative system revolves around producing consumer satisfaction. This involves an active engagement with the citizen as a consumer of public services, and a responsiveness by the administration to dissatisfaction on the part of its consumers. The levels of service to be enjoyed by consumers, the standards of good administration, are often defined in ‘customer charters’. In contrast to managerialism, accountability comes from the ground up – from the consumers themselves - through complaints systems.

The final ideal type added by Adler is that of the market. Here the administrative system is driven by the goal of competitiveness. The citizen here is viewed as a rational customer choosing services from a range of providers. The administrative system revolves around making its services as attractive to the customer as possible. Whereas under consumerism the administrative system was accountable to citizens through complaints systems (‘voice’), under the market ideal type, the administrative system is accountable to the market itself and subject to the ever present possibility that the citizen will choose another service provider (‘exit’).

BUILDING ON MASHAW AND ADLER

The typologies of Mashaw and Adler are important and insightful. Both have been influential within the field of administrative justice research. Their work also represents a formidable basis from which to begin the task of constructing a new typology. With this in mind, we should again state clearly the nature of our contribution in this chapter. In keeping with the intentions of Mary Douglas who developed the grid-group analytical framework, ‘the object is not to come up with something original, but gently to push what is known into an explicit typology that captures [existing] wisdom...’. (1982a: 1).

Specifically, we aim to construct a typology of administrative justice along two dimensions derived from grid-group cultural theory. This, we believe, has at least two benefits. First, it permits us to understand better how different ‘ideal types’ relate to each other. A disadvantage of Mashaw’s typology is that this relational quality is absent. It is not clear from his account how, if at all, the various ideal types are connected. Of course, this is simply an unavoidable limitation of the method he adopted to construct his typology. As noted above, Mashaw in large part derived his ideal types from the range of critical literature around US disability benefits administration. However, where typologies are created to match observation in this way there is a danger that categories are formed from different dimensions and that the resulting typology is uneven or lopsided - what Thompson et al. describe as “categorical ad hocracy” (1990: 14). By way of contrast, building a typology along two dimensions gives us basic criteria with which to compare existing administrative processes. Typologies should aid comparison and the use of these two dimensions is a key enabling feature towards this end. A typology using dimensions offers us a better method for understanding the ways in which, and the extent to which, various administrative processes differ from each other in terms of their values, qualities and underlying logic.

Indeed, the typology developed by Kagan (in this volume) is very helpful in this regard. He offers us dimensions which allow us to see how Mashaw’s models of justice relate to each other. We may recall that Kagan sets out two dimensions: (1) participatory – hierarchy, and (2) legal formality – legal informality. If we impose these dimensions onto Mashaw’s schema, we can see that bureaucratic rationality corresponds to Kagan’s category of ‘bureaucratic legalism’ as a product of hierarchy and legal formality, professional treatment corresponds to Kagan’s category of ‘expert or political judgment’ as a combination of hierarchy and legal informality, and moral judgment corresponds to ‘adversarial legalism’ as a combination of participation and legal formality. Further, a comparison between Kagan’s typology and that of Mashaw reveals that Mashaw’s typology was indeed lopsided. Kagan’s addition of ‘mediation/negotiation’ as a combination of participation and informality balances out and completes Mashaw’s contribution.

The second benefit to be gained from developing a cultural typology of administrative justice is that, given the scope and ambition of grid-group theory, we believe it is possible to build a typology which is exhaustive in the sense that it captures all observed and potential forms of administrative justice. One of the limitations of Mashaw’s work is that it was a product of a particular method at a particular moment in time in US political history. By its nature, then, we should not expect his typology to be exhaustive. Indeed, Adler demonstrated precisely that in updating Mashaw’s typology some years later in the context of contemporary UK public administration, taking account of the emergence of the new public management. However, our argument is that, even with the addition of Adler’s work, there is more to be said about administrative justice. In fact, following on from our discussion above, Adler’s contribution to Mashaw and Kagan renders the overall schema lopsided again. Our intention is to map the existing typologies onto a much larger analytical frame in a way that sheds light on the dimensional connections between Adler, Mashaw and Kagan, and reveals further conceptions of administrative justice not hitherto explored in the literature. First, however, we must explore grid-group cultural theory and its potential for distilling a broad typology of administrative justice.

GRID-GROUP CULTURAL THEORY

As already noted, our starting point for constructing our typology is the cultural theory of Mary Douglas (1982a, 1982b), developed most notably by Thompson et al. (1990). Although this theoretical framework is now well established within the social sciences, and has been used extensively by Christopher Hood in his analyses of public administration (Hood 1998, Hood, et al. 1999, Bevan and Hood 2006) and by Fiona Haines (2005) in her study of regulation, it is worth summarising again for the purposes of this chapter. As we will see, grid-group cultural theory shares the normative pluralism of Mashaw and Adler. However, it argues that this pluralism is limited by virtue of being structured around two basic dimensions: grid and group.

The epistemological starting point of grid-group cultural analysis is that human perception and consciousness are mediated by culture. But cultures vary, of course. Drawing on a wealth of anthropological studies from various parts of the world, Mary Douglas developed her analytical framework as a way of facilitating meaningful comparisons between cultures – a framework for showing the basic ways in which cultures differ from each other. Grid-group cultural theory reduces social variation to a “few grand types” (Douglas 1982a: 2). The two dimensions of ‘grid’ and ‘group’ produce four ideal types of cultural bias – “four extreme visions of social life” (Douglas 1982a: 2). The dimensions reflect the answers to two basic questions: ‘who am I?’ (group) and ‘how should I behave?’ (grid) (Thompson and Wildavsky 1986). According to Thompson et al. (1990),

‘[t]he variability of an individual’s involvement in social life can be adequately captured by two dimensions of sociality: grid and group. Group refers to the extent to which an individual is incorporated into bounded units. The greater the incorporation, the more individual choice is subject to group determination. Grid denotes the degree to which an individual’s life is circumscribed by externally imposed prescriptions. The more binding and extensive the scope of the prescriptions, the less of life that is open to individual negotiation.’ (ibid: 5)

From this very general starting point, grid-group cultural theorists have developed an exhaustive typology of cultural biases corresponding to the four[5] possible combinations of the grid and group dimensions. A cultural bias is a way of seeing the world, a set of mutually supportive assumptions and values that make up a coherent approach to life. The claim is that cultural biases may colour everything from the social construction of nature, to perceptions of risk and blame, to normative views about political culture. Hood (1998), for example, has applied the notion of cultural bias to develop a basic typology of approaches to public management. As he notes, the theory ‘aims to capture the diversity of human preferences about “ways of life” and relate those preferences to different possible styles of organisation, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages but is in some sense “viable”.’ (1998: 7)

In the same way, we suggest, the analytical framework offered by grid-group cultural theory permits us to develop a pluralistic but exhaustive typology of “the qualities of a decision process that provide arguments for the acceptability of its decisions” (Mashaw 1983: 24).

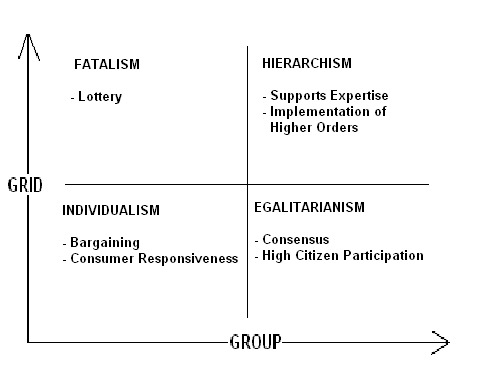

The four cultural biases can be summarised as follows:

Low-group / low-grid – ‘individualism’

For the individualist all boundaries are open to negotiation. The individual enjoys the capacity for mobility up and down without barriers of rank or status. S/he is free to operate unconstrained by the pressures of group membership or normative prescriptions about how and when s/he can relate to others and engage with society. In keeping with a perspective which stresses the pursuit of individual self-interest, the individualist seeks to replace authority with regulation of the self.

Low group / high grid – ‘fatalism’

The fatalist feels constrained and controlled by societal norms and issues of rank, role and status. But at the same time the fatalist is isolated and excluded from group membership. The fatalist, then, is marked by a sense of powerlessness and resignation. Life seems unpredictable. Good times or bad times appear to come to him regardless of his skill, character or diligence.

High group / high grid – ‘hierarchism’

The combination of high grid and high group means that hierarchism is marked by a respect for expertise and authority and a sense of the collective. Loyalty is rewarded and hierarchy respected. The exercise of authority and the existence of inequality are justified on the grounds that they enable people to live together harmoniously. All benefit from such authority and expertise as it is exercised for the common good. The individual knows his/her place in a world that is securely bounded and stratified.

High group / low grid – ‘egalitarianism’

By way of contrast to hierarchy, there is a suspicion of authority within egalitarianism. A sense of the collective exists, but the aims of the group, and the means of achieving them, must be decided by the group members on an equal basis. Although the boundary of the group is clear, producing insiders and outsiders, within the group all statuses are ambiguous. Equality and consensus are key themes within egalitarianism.

Figure 1: Grid Group Analytical Framework of Cultural Biases

GRID GROUP CULTURAL THEORY AND PUBLIC MANAGEMENT

The above overview, by its nature, is cast in fairly broad terms. Its vantage point is high and its scope wide. Nevertheless, we suggest that grid-group cultural theory can be harnessed and applied to the concept of administrative justice to develop ideal types. Our first step in this process is to consider the work of Christopher Hood who has explored how cultural theory might be applied to ways of organising public administration. As Hood (1998: 8) points out, ‘[p]ut the “grid” and the “group” dimensions together, and they take us to the heart of much contemporary and historical discussion about how to do public management’.

According to Hood, each cultural bias described by cultural theory produces a distinct and basic logic of ‘good administration’. For the individualist, good administration takes place within a market and is driven by competitive forces. For the hierarchist, good administration harnesses and relies on expertise and authority within government. For the egalitarian, it is marked by consensus between public officials and the citizens they serve. These three ideal types, of course, match widely recognised and basic modes of governance: hierarchy, market and community (Scott 2006, Mashaw 2006).

It is harder to derive an image of ‘good’ administration from fatalism. Fatalism, as its name suggests, is a negative view on life – a sense of powerlessness and exclusion. At the level of the individual, we may associate it with the classic “lumpers” (Genn 1999) and “sceptics” (Cowan and Halliday 2003) in relation to disputing, and with “withdrawal” tendencies in relation to citizens’ use of public services (Simmons et al. 2007). More generally, as a cultural bias fatalism lacks the trust in government associated with hierarchism, and the sense of freedom in a market marked by individualism. The fatalist’s observation of life is that it is random and unpredictable. Fatalism, then, entails an abandonment of a belief that outcomes can be achieved through positive action. Nevertheless, from this negative ‘is’ we may derive the positive ‘ought’ that public management should also (or, at least, might as well) reflect this unpredictability. As Thompson et al. note, although analytically defensible, the fact/value distinction obscures the extensive interpenetration of facts and values in the real world:

[w]ays of life weave together beliefs about what is... with what ought to be... into a mutually supportive whole. (1990: 22)

In this vein, Hood introduces the notion of “how-to-do-it ideas” (1998: 14) whereby fatalism can be linked to prescriptions for positively designing institutions. He links what he terms “contrived randomness” as such a prescription with a fatalistic cultural bias. Hood refers here to situations where chance is used as a central aspect of organisational life. Random internal audits, for example, capture contrived randomness. Similarly, an organisation might make working conditions unpredictable. If officials are posted unpredictably, and so cannot know with whom they will be working, by whom they will be supervised, who will be their clients and so forth, they can be prevented from joining with colleagues or clients to organise ‘scams’ or anti-system conspiracies. ‘Contrived randomness’, Hood suggests, can be seen in parts of the civil service, the tax bureaucracy or the military where postings are of limited-term or where relative strangers are required to work together on projects.

A CULTURAL TYPOLOGY OF ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE

The final stage in constructing our typology is to consider the implications of these ways of organising public administration for administrative process. What characteristic decision-making processes emerge from these ideal types of public management and what are the justifications for them which reflect the various cultural biases? These are set out below and summarised in Figure 2.

‘Hierarchist’ administrative justice

The combination of high grid and high group means that considerable value is placed on authority and expertise. Within the hierarchist bias, government is trusted to act on behalf of the collective. Citizens are not expected to participate in decision-making processes. Public officials, rather, are expected to exercise their skill and judgement for the public benefit, and citizens are content to be passive objects of this official discretion – such is their station. Decision-making processes within hierarchism should support the exercise of expert judgement and/or the accurate and efficient implementation of higher orders.

‘Egalitarian’ administrative justice

By way of contrast, the egalitarian bias with its combination of low grid and high group is sceptical and distrustful of governmental authority and expertise. It favours decision-making by consensus and seeks to equalise the position of all those in the group. In the context of administrative justice, this translates into citizens and public officials being equal partners in decision-making processes. Decision-making processes within egalitarianism should be all about reaching consensus and so marked by very high citizen participation.

Administrative law’s affinity with hierarchism-egalitarianism

We can note at this stage that Kagan’s vertical dimension of ‘participatory – hierarchy’ set out in his chapter in this book corresponds to the vertical ‘grid’ dimension of cultural theory. However, the continuum running between a hierarchist conception of administrative justice and an egalitarian conception should also be familiar to administrative lawyers. It is reflected to a notable extent in administrative law doctrine. The flexibility of the doctrine of procedural fairness, for example, captures the shifting strength of administrative protections relating to citizen participation. Indeed, the connection between hierarchism’s and egalitarianism’s visions of administrative justice parallels the continuum drawn by Galligan between what he calls ‘bureaucratic administration’ and ‘fair treatment’ (1996: 237-40). The variability of the intensity of judicial review – the competition between judicial control and agency autonomy (Craig 2003: 510) - also reflects the extent to which the expertise and authority of government should be respected and supported. We might frame the extent of citizen participation in decision processes as capturing the core element of grid-group cultural theory’s application to administrative justice.

We must stress, however, that there are further gradations of citizen participation which lie beyond these analyses and towards the ideal of decision-making by consensus. Legal theories of administrative justice, including that of Mashaw, are somewhat narrower (or shorter) than our cultural analysis of administrative justice. Decision-making by consensus between officials and citizens is a conception of administrative justice which has received insufficient attention in the field.

‘Individualistic’ administrative justice

As we noted above, individualism is marked by the ability of individuals to negotiate their own way through life, untrammelled by group mandates and social rules and prescriptions. This produces a cultural bias which revolves around self-interest and personal responsibility and sees the market as the appropriate model of social organisation. Hood (1998) applies this directly to public management and draws out an ideal type where public services are delivered in a competitive environment. But one might still legitimately wonder what the characteristic decision-making process is which reflects this image of good administration. Sainsbury, for example, reflecting on Adler’s work, has questioned whether conceptions of administrative justice associated with new public management reveal any new and distinctive decision processes on a par with Mashaw’s description of (1) of implementation of rules (bureaucratic rationality), (2) the application of expertise (professional treatment), or (3) the judging between competing claims (moral judgment) (Sainsbury 2008). It is clear that individualism has influenced the organisation of public management (Hood 1998), including various features of public accountability. The rise of complaints systems are but one example (Simmons et al.. 2007). But, recalling our earlier distinction between decision processes and other features of public accountability, does this fail to alter the fact that the decision-process itself is non-individualist? For example, even although medical practitioners may be the subject of customer satisfaction surveys, their decision-making as doctors may still comprise the application of expertise. Equally, although public agencies may have to provide services in a competitive environment and so be incentivised (perhaps financially) to improve the customer experience, alterations may not relate to the actual mode of decision-making, but rather to additional aspect of service delivery such as waiting times, courtesy, clarity of communication, and so forth. To what extent, then, can we identify a distinctive decision process associated with an individualistic cultural bias?

The answer is that bargaining is the characteristic mode of decision-making in market settings. This is a decision process about reaching consensus (just like egalitarianism) but not within the context of a group. Rather, the citizen-consumer is in the driving seat. It is about matching supply to individual demand. This permits us to suggest that in the context of administrative justice, an individualistic cultural bias would produce an ideal typical decision process which involves bargaining and consumer responsiveness. The market is a mode of social organisation which encourages suppliers to carve out some kind of competitive advantage for themselves. An individualist system of decision-making would be organised to privilege agency competitiveness and customer satisfaction over other values. Accuracy and expertise are not important values in themselves in the context of individualism. Within individualism it is the customer who is always right and who always knows best. To the extent, then, that decision-making systems privilege customer care and satisfaction to the exclusion of accuracy and expertise, we are seeing the influence of an individualistic approach to administrative justice. Indeed, we might suggest that the extent of agency responsiveness to consumer needs and desires captures the core of the ‘group’ dimension of cultural theory when applied to administrative justice.

‘Fatalistic’ administrative justice

Fatalism represents terrain that has largely been unexplored in relation to administrative justice. The suggestion of a fatalistic conception of administrative justice, then, offers something quite distinctive to the field, albeit potentially controversial. Within fatalism life is unpredictable - sometimes good, sometimes bad. A general sense of powerlessness and exclusion produces a cultural bias which permits no positive prescription for achieving outcomes. It is difficult to derive directly a notion of administrative justice from Hood’s description of ‘contrived randomness’ as an ideal type of public management. However, we may follow Hood’s example of developing a ‘how-to-do-it’ idea which reflects a fatalistic cultural bias. In this vein we can focus on the notion of a lottery as a characteristic decision-making process within fatalism. Although there may be a temptation to associate lotteries with egalitarianism or notions of equality – the idea that lotteries are fair because everyone has an equal chance of winning – this is to confuse ends with means. The point about fatalistic administrative justice is that the active use of randomness in decision-making processes marks the abandonment of any faith in our ability to positively design just processes of administration. Instead, we delegate responsibility to the Fates.

Figure 2: A Cultural Typology of Administrative Justice

Ideal types and social reality

We should stress, of course, that the above are ideal types. Ideal types are analytical mechanisms – combinations of dimensional extremes - designed to help us understand a much messier social reality. A typology offers us the tools with which we may compare and contrast varying visions of ‘good administration’. Importantly, then, our ideal types are normative and not descriptive. We recognise that our typology can be used to help characterise real-world decision processes and, more significantly, to distinguish between processes. Equally, we recognise the intimate relationship between the normative and the descriptive in that real-world decision-making processes are designed with normative aims and values in mind. Nevertheless, the character of our typology is not primarily descriptive. Rather, we have constructed a broad framework which captures (1) the variety of ways in which one might possibly design a decision-making process, and (2) the underlying justifications for such designs: to use Mashaw’s phrase again, “the qualities of a decision process that provide arguments for the acceptability of its decisions.” (1983: 24) For these reasons, we should not expect to find such ideal types in pristine form in the real world. They operate on an analytical rather than empirical level. Moreover, as a framework of normative ideals, they will inevitably be broader than what we see in the real world with all its familiar compromises and imperfections. In other words, the cogency of this cultural typology of administrative justice should not be judged by testing it against empirical descriptions of real-world public administration. We should not approach the typology through the lens of empirical reality. Rather, we should observe, describe and compare empirical realities through the lens of this normative typology.

Notwithstanding the above, we recognise that our typology will fail to have any analytical purchase if it bears no relation whatsoever to what we can see in, or imagine about, administrative processes in the real world. Further, by pointing to familiar decision processes within public administration and divining their underlying rationales, it may help to bring our typology into focus a little more. We suggest that it is not hard to identify elements of these ideal types at play within public administration.

Hierarchism

The familiar development and implementation of policy within many front-line public bureaucracies reflects a hierarchist bias. Of course, empirical research about street-level bureaucracy (Lipsky 1980) paints a complex picture of implementation where ‘policy’ is formed from the bottom-up as much as from the top-down. Nevertheless, it is still not hard to see in the design of policy programmes in domains such as social security, housing and social work the importance attached to the implementation of rules and the application of expertise.

Egalitarianism

Hood (1998: 62) notes that the egalitarian bias can be

‘applied to the control of public-service provision by society at large. At that level, the formula implies maximum face-to-face interactions between public-service producers and clients, and indeed as far as possible a dissolution of the difference between ‘producer’ and ‘client’ altogether.’

A good example of importance being attached ‘group’ decision-making, one which takes us beyond the level of citizen participation usually envisaged by administrative law doctrine, lies in consensus-seeking in regulatory policy-making (Coglianese 2001). To a lesser extent, the stress on community consultation in areas of policy such as planning and education also reflects an egalitarian bias.

Fatalism

In relation to fatalism, there are some clear contemporary examples of government making decisions through random processes. The selection of persons to serve on juries is an example (Duxbury 1999). Randomness rather than reason is judged to be fairest both to those selected to serve and to criminal defendants. Randomness is also seen in some allocation of school places (Turvey 2008) and, in some countries, in immigration visa lotteries. Randomness only features as the basis for the justice of an administrative decision where it is deliberate. Accordingly, other metaphorical lotteries, such as the ‘postcode lottery’ in provision of healthcare in different regions, are not included within this discussion.

Individualism

It is clear that public service delivery has in recent decades been significantly affected by individualist approaches to public management (though these ideas have a much longer pedigree – see Hood 1998, chapter 5). Managerialism, consumerism and marketisation in the public sector certainly reflect the individualist cultural bias particularly clearly. But is there any evidence of bargaining or the matching of supply to demand in contemporary administrative processes? In many policy domains, such as social security administration, it may be difficult to conceive of such a thing. However, bargaining is far from uncommon in other policy areas such as environmental regulation enforcement (Hawkins 1984) or telecommunications regulation (Hall et al. 2000). As Hall et al. (ibid: 111-2) note in relation to their observation of a ‘diplomatic-bargaining’ style of decision-making within Oftel:

‘[s]uch a style is commonly observable in institutional decision-making generally... and in regulatory decision-making more particularly... and links in to a vast literature on negotiation and bargaining within organisations and policy communities. It is less programmed than the Cartesian-bureaucratic style, in that the final outcome depends on what the various participants will accept rather than on the pre-set objectives of any one organisation. (2000: 111-2)

REFLECTIONS ON MASHAW, ADLER AND KAGAN IN LIGHT OF CULTURAL THEORY

Having constructed a basic typology of administrative justice from grid-group cultural theory, we must now return to the typologies of Mashaw, Adler and Kagan. To what extent can we map their models or ideal types onto ours?

Mashaw

Starting with Mashaw, we can see that his ‘moral judgment’ model with its stress on “preserv[ing] party equality and control”, “promot[ing] agreed allocations” and the “application of common moral principles” (1983: 31), betrays an egalitarian stress on participative decision-making processes which aspire to consensus. Although, as we suggested above, the extent of participation may be stronger, ‘moral judgment’ represents a move ‘down grid’ from hierarchism and so may be associated with egalitarianism. We can also suggest that Mashaw’s ‘bureaucratic rationality’ model with its focus on the “correct implementation of otherwise legitimate social decisions” (1983: 26) fits well with the hierarchist stress on accurate and efficient implementation of higher orders. But what about Mashaw’s ‘professional treatment’ model with its stress on the application of professional or clinical judgment? This too would seem to fit well with a hierarchist vision of administrative justice which additionally stresses the value of expertise and the importance of decision-making processes which support such expert judgments. We suggest that Mashaw’s ‘professional treatment’ model and his ‘bureaucratic rationality’ model do, indeed, both fall within a hierarchist ideal type of administrative justice. As Hood notes, “[h]ierarchism is not a single organizational model but a family of related approaches, differing in the way that ‘groupness’ and ‘gridness’ are manifested.” (1998: 97). Hood distinguishes (1998: 75) between types of rule (immanent and enacted) and types of groups (task or profession-specific and public-sector-specific). This produces different types of hierarchist organisation and can account for the difference between the ‘bureaucratic rationality’ and ‘professional treatment’ visions of administrative justice. ‘Professional treatment’ has a greater stress on professional expertise and the application of immanent rules, akin to a traditional professional organisation such as medicine. ‘Bureaucratic rationality’ has a greater stress on a more generic public-sector specific group, implementing enacted rules. Kagan’s distinction (in this volume) between legal formality and legal informality is also helpful here, as noted earlier. But both models of administrative justice reflect a hierarchist bias with its focus on public officials fulfilling their authoritative and expert roles on behalf of the collective. The difference between professional treatment and bureaucratic rationality, then, reflects a second-order distinction, rather than a first-order distinction which accounts for the difference of them both from ‘moral judgment’.[6] As a whole, Mashaw’s typology would fit within the right-hand side of our cultural typology of administrative justice.

Adler

Turning to Adler, how should we interpret the ideal types he suggests: ‘consumerism’, ‘markets’ and ‘managerialism’? To do this we must recall the important distinction we made earlier between decision-making processes and other features of public management and accountability. What are the actual decision-making processes inherent in Adler’s ideal types? Consumerism, according to Adler (2003: 334).

‘embodies a more active view of the service user, who is seen as an active participant rather than as a passive recipient of bureaucratic, professional, or managerial decisions. It can thus be characterised in terms of the active participation of consumers in decision-making, customer satisfaction, the introduction of “consumer charters,” and the use of “voice.”’.

The stress on consumer participation and agencies’ pursuit of customer satisfaction suggests that ‘consumerism’ fits very well within our category of individualism. Similarly with ‘markets’: “decision-making in the market involves the matching of demand and supply and is made with reference to the price mechanism.” (2003: 334) Adler’s category of ‘markets’, then, would also seem to fit squarely within our category of individualism. Indeed, we might question whether ‘markets’ and ‘consumerism’ betray any real difference in terms of decision-making processes per se. To what extent is the matching of demand and supply different from the participation of consumers in decision-making with a view to customer satisfaction? At most, we suggest, these would reflect only slight gradations within individualism. Managerialism, we suggest, is more problematic as an ideal type of administrative justice. Although Adler is correct to highlight changes in public management which reflect managerialism – the rise of managerial autonomy, performance audit and performance rewards – it is unclear to us that managerialism betrays a distinctive decision-making process. Nevertheless, in ‘consumerism’ and ‘markets’ Adler has made an important contribution which would fall within the bottom left hand quadrant of our cultural typology of administrative justice.

Kagan

We noted above that Kagan’s typology outlined in his chapter in this book helps us reflect on Mashaw. We suggested that Kagan’s categories of ‘bureaucratic legalism,’ ‘expert or political judgment’ and ‘adversarial legalism’ could be mapped onto Mashaw’s categories of ‘bureaucratic rationality’, ‘professional treatment’ and ‘moral judgment’. A question remains, however, about how to interpret Kagan’s category of ‘negotiation/mediation’, a combination of participation and legal informality. Although Kagan uses the language of ‘negotiation’, it is not in the same sense, we suggest, as we have used it in relation to individualism. Rather Kagan (in this volume) is referring to a decision-making process which

‘allows the individuals or organizations subject to the agency’s authority... considerable opportunity to present and argue their cases in an informal manner. In this modality, regulatory officials charged with implementing anti-discrimination or consumer protection law, for example, often mediate disputes between a complainant and an employer or a merchant, fostering a negotiated settlement. The process is nonlegalistic, since neither procedures nor substantive dispositions are dictated by formal law.’

We can see the parallel with ‘moral judgment’ whereby a decision must be reached in relation to competing interests. Further, the pursuit of a mediated solution agreeable to the parties, and participation of the parties in reaching that solution reflects something an egalitarian bias. Accordingly, we suggest that this is a helpful second-order distinction to be made in this regard and an important addition. Kagan’s typology, then, like Mashaw’s, fits within the right-hand quadrants within our wider cultural typology of administrative justice.

CONCLUSIONS

This chapter has offered an elaboration and theorisation of the variety of models of administrative justice found in the literature. If cultural theory is of value in abstracting from these different analyses of administrative justice, it is in offering a complete set of family of forms of administrative justice. This permits us to see better the connections between differing visions of administrative justice discussed in the existing literature. Cultural theory also significantly expands the scope of administrative justice theory. Indeed, the exercise of mapping existing typologies onto our cultural framework reveals that existing work on administrative justice is relatively narrowly framed. Traditional legal conceptions of administrative justice are restricted to the right-hand side of our framework and do not exhaust the full potential of the egalitarian vision of administrative justice with its stress on decision-making by consensus. Adler has certainly offered an important complement to legal conceptions by focusing our attention on individualism. However, there has still been a general failure hitherto to engage with the existence of potential of fatalistic modes of administrative justice.

At the beginning of this chapter we noted that it is wise, in developing ideal typologies of this kind, to acknowledge previous significant works in the field. We might add here that it is also wise to stress the limitations of our work. The ambition of this chapter has been fairly modest: it was simply to construct a typology which we believe can be useful as an analytical tool in the field. As an analytical tool it could be put to many purposes, but we have not pursued them here. In particular, given that typologies aid comparison, it might be used as a foundation for characterising changes in the style of administrative justice within particular public agencies across time, or between various public agencies within a fixed time period. Equally, it might generate questions about why particular modes of administrative justice become dominant at particular moments in particular agencies. Important work in this regard has been carried out,[7] including by those we have discussed in this chapter.[8] More work in this regard would be beneficial for the field. Further still, if one approaches the issue of administrative justice through the lens of everyday legal consciousness, such as Marc Hertogh’s chapter in this volume, cultural theory and a typology of administrative justice may help us understand the varieties of ways in which people, including public officials, engage with administrative legality and process (or it may act as a useful foil). However, despite the insights of existing work, and the importance of such research projects, we must stress that our contribution in this chapter is preliminary to this kind of scholarship.

REFERENCES

Adler, M (2003) ‘A Socio-Legal Approach to Administrative Justice’ 25 Law and Policy 323

Adler, M (2006) ‘Fairness in Context’ 33 Journal of Law and Society 615

Adler M (2008) ‘‘The Justice Implications of “Activation Policies” in the UK’, in Erhag, Thomas, Stendahl, Sara and Devetzi, Stamatia (eds) A European Work-First Welfare State, Göteborg: University of Göteborg: Centre for European Research.

Adler, M. and Longhurst, B. (1994), Discourse Power and Justice, (London, Routledge)

Bevan, G and Hood, C (2006) ‘What's Measured Is What Matters: Targets And Gaming In The English Public Health Care System’ 84 Public Administration 517.

Buck T (1998) ‘Judicial Review and the discretionary Social Fund: The Impact on a Respondent Organization’ in Buck T. G. (ed) Judicial Review and Social Welfare (London and Washington, Pinter)

Coglianese, C (2001) ‘Is Consensus an Appropriate Basis for Regulatory Policy?’ in Orts, Eric and Deketelaere, Kurt (eds) Environmental Contracts: Comparative Approaches to Regulatory Innovation in the United States and Europe (The Hague, Kluwer Law International)

Cowan, D and Halliday, S (2003) The Appeal of Internal Review (Oxford, Hart Publishing)

Craig, P (2003) Administrative Law (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Douglas, M (1982a) ‘Introduction to Group-Grid Analysis’ in Douglas, Mary (ed) Essays in the Sociology of Perception, (London, Routledge and Kegan Paul)

Douglas, M (1982b) ‘Cultural Bias’ in Douglas, Mary (ed) In the Active Voice (London, Routledge and Kegan Paul)

Duxbury, N (1999) Random Justice (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Galligan, D (1996) Due Process and Fair Procedures (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Genn, H (1999) Paths to Justice (Oxford, Hart Publishing)

Hall, C, Hood, C and Scott, C (2000) Telecommunications regulation: culture, chaos and interdependence inside the regulatory process (London, Routledge)

Haines, F (2005) Globalization and Regulatory Character (Farnham, Ashgate).

Hawkins, K (1984) Environment and Enforcement (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Hood, C (1998) The Art of the State: Culture, Rhetoric and Public Management (Oxford, Oxford University Press)

Lipsky, M (1980) Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (New York, Russell Sage)

Mashaw, J (1983) Bureaucratic Justice: Managing Social Security Disability Claims (New haven, Yale University Press)

Mashaw, J (2006) ‘Accountability and Institutional Design: Some Thoughts on the Grammar of Governance’ in Dowdle, M (ed) Public Accountability (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press)

Sainsbury, R (2008) ‘Administrative Justice, Discretion and the ‘Welfare to Work’ Project’ 30 Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 323.

Scott, C (2006) ‘Spontaneous Accountability’ in Dowdle, M (ed) Public Accountability (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press)

Simmons, R, Birchall, J, and Prout, A (2007) ‘Hearing Voices: user involvement in public services’ 17 Consumer Policy Review 234

Sunkin, M and Pick, K (2001) ‘The Changing Impact of Judicial Review: The Independent Review Service of the Social Fund’ Public Law, 736

Thomson, M, Ellis, R and Wildavsky, A, (1990) Cultural Theory (Boulder, Westview Press)

Turvey, K (2008) ‘The Loaded Die is Cast’ The Guardian (http://education.guardian.co.uk/admissions/story/0,,2264168,00.html) last accessed 6th May.

7.981 words (with footnotes)

[1]

Law School, University of Strathclyde; Faculty of Law, University of New South

Wales

[2]

School of Law, University College Dublin

[3] The research on which this chapter draws was generously funded by the Nuffield Foundation and we are very grateful for its financial support. Additionally, the Nuffield Foundation hosted a seminar where a preliminary analysis was presented to a group of academic experts. This was a lively event from which we gained a great deal. We are very grateful to the following people who took part: Michael Adler, Varda Bondy, Trevor Buck, Sharon Gilad, Jackie Gulland, Jeff King, Richard Kirkham, Rick Rawlings, Genevra Richardson, Roy Sainsbury, Richard Simmons, Brian Thompson, and Sharon Witherspoon. We also benefited from written comments after the event from a number of those who attended.

[4] By way of contrast, the stress Sainsbury (2008) places on ‘moral judgment’ envisions the situation where a public agency has to decide between completing claims of citizens such as planning decisions

[5] Thompson et al. (1990) include a fifth bias – that of the hermit who has withdrawn from coercive social relations and so is ‘off the map’. For this reason we do not apply or operationalise this cultural bias.

[6] This analysis makes some connection, then, with Galligan’s view that ‘professional treatment’ falls within the continuum between his models of ‘bureaucratic administration’ and ‘fair treatment’ (1996: 237).

[7] See, for example, Buck (1998), Sunkin and Pick (2001) and Sainsbury (2008).

[8] Adler and Longhurst (1994), Adler (2008) and Kagan (in this volume).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2009/3.html