Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

DIETRICH FAUSTEN,[∗] INGRID NIELSEN[†] AND RUSSELL SMYTH[‡]

[Examination of citations contained in the written record of judicial decisions provides useful insights into the evolution of the jurisprudence and policy of particular courts, and of the judges who make significant contributions to those courts. This article examines the citation practice of the Supreme Court of Victoria over the century 1905–2005 at 10‑year intervals. It employs the McCormick taxonomy of citations, which distinguishes between consistency, hierarchical, coordinate and deference citations and also tracks citations to secondary authorities. The major findings of the study are that the length of judgments and the number of authorities cited by the Court have increased over time, and that consistency and hierarchical citations have been the dominant form of allusion to prior authority.]

CONTENTS

A defining feature of judicial power in Australia, as throughout most of the common law world, is that appeal court judges are required to give written reasons for their decisions.[1] Lord Denning has stated that giving written reasons is ‘the whole difference between a judicial decision and an arbitrary one’.[2] These written reasons are typically supported by citation to previous authorities. Citation to previous authorities provides a means for judges to relate their reasons back to their previous decisions and the decisions of other courts. This practice provides protection against arbitrary decision making. As Lawrence Friedman and his colleagues put it, judges are expected to decide ‘according to the law’, which means ‘they are not free to decide cases as they please, [but instead] are expected to invoke appropriate legal authority for their decisions’.[3] Citations to previous authorities are therefore one way for judges to give their decisions legitimacy.[4] This is important because legitimacy is seen by some as affecting the reactions of the other branches of government to judicial policies.[5]

Judicial citation practice provides a window into the courts — and even the judges — which are making the most important contributions to the evolution of the judicial branch’s jurisprudence and policy.[6] In this respect, William M Landes and Richard A Posner postulated that the number and average age of citations are important indicators of a court’s use of precedent.[7] Citations have been used to show how judges make law through tracing judicial innovation[8] and communication between courts.[9] An examination of citation practice may also reveal where judges find their cues and what values they seek to promote.[10] ‘Citation patterns … reflect conceptions of role. … These patterns may be clues, too, to the role of courts in society’.[11]

The study of judicial citation practice has gained considerable momentum during the last two decades, particularly in North America. There are studies of citation practice for the Supreme Court of the United States,[12] the US courts of appeals,[13] US state Supreme Courts,[14] the Supreme Court of Canada[15] and the Canadian provincial courts of appeal.[16] A smaller number of studies have considered the citation practice of courts in Australasia. There are, however, studies for the High Court of Australia,[17] Federal Court of Australia,[18] the Australian state Supreme Courts[19] and the New Zealand Court of Appeal.[20] Because of the financial cost of collecting large datasets, most studies have focused on citation practice within a single year or a few select years. There are few studies for North America that examine citation practice over an extended period of time[21] and no such studies for Australasian courts.[22]

This article examines the citation practice of the Supreme Court of Victoria in decisions published in the Victorian Reports at 10‑year intervals between 1905 and 2005.[23] The citation practice of an intermediate appellate court such as the Supreme Court of Victoria is instructive for several reasons.[24] First, the Supreme Court of Victoria is an important legal institution. As the highest court in the state, its decisions shape how the law develops in Victoria. Secondly, although the empirical results reported in this article are for one state only, the implications of the analysis extend beyond Victoria. The Supreme Courts of other Australian states and territories — and indeed, intermediate appellate courts in other common law jurisdictions — share many of the same characteristics as the Supreme Court of Victoria, including the requirement to give reasons and justify their decisions through the citation of authority. Thirdly, from a practical perspective, the data should provide useful information to practitioners who wish to know which authorities the Supreme Court considers important, and to libraries — particularly the libraries of the state Supreme Courts — which could fruitfully use the tabulated data as a basis for discussion about which authorities to make available.

There is one existing study of citation practice in the Supreme Court of Victoria, which analyses citation practice in reported decisions published in the Victorian Reports in 1970, 1980 and 1990.[25] Compared with that study, this study examines citation practice over a much longer period. The additional seven decades analysed in this study permit greater richness of interpretation that was not possible in the earlier study.[26] For instance, the longer time span should make it easier to detect temporal trends in citation practice as well as ascertain the ease and extent to which the Court has adopted new and novel types of authority. If citation patterns reflect a court’s conception of its role in society, as suggested by Friedman et al,[27] the current study will allow for the detection of changes in the Court’s conception of its role in society over a century spanning from the early Edwardian period to the 21st century.

Peter McCormick suggests that there are several categories of judicial citation.[28] Consistency citations are those referring to previous decisions of the citing court. McCormick suggests that ‘the general principles of continuity and consistency and the legal value of predictability in the law require that [previous decisions] carry considerable weight’.[29] John Merryman echoes these sentiments, stating: ‘Where the court has spoken the strongest case for stare decisis is presented’.[30] In Nguyen v Nguyen, Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ (Brennan and Deane JJ agreeing) stated that, in general, the extent to which a full court of a state supreme court regards itself at liberty to depart from its own previous decisions is for the court itself to determine.[31] In Victoria, the Full Court of the Supreme Court of Victoria reserves to itself the freedom to reverse its own previous decisions. Beginning with Forster v Forster,[32] the usual practice has been for a Full Court of five or more judges to be convened if an earlier decision of a Full Court of three judges is to be reviewed.[33] There have, however, been some exceptional circumstances where an earlier Full Court decision has been reconsidered without a Full Court of five or more judges being convened. In Avco Financial Services Ltd v Abschinski a Full Court of three judges decided not to follow an earlier Full Court decision.[34] In R v Tait, sitting in the Victorian Court of Appeal, Callaway JA (Winneke P and Crockett AJA agreeing) stated: ‘It may be that in future we would extend those exceptional circumstances to enable a greater number of Full Court, and in due course some of our own, previous decisions to be reviewed by a court of three.’[35]

A decision of the Full Court or Court of Appeal binds a single judge sitting alone. In Engebretson v Bartlett it was decided that a decision of the Full Court in banc has the same precedential value as a decision of the appellate Full Court.[36] In the absence of a binding decision of a higher court, the practice in state and territory Supreme Courts in Australia is that a judge sitting alone will normally follow the earlier decision of a single judge of the same court sitting alone.[37] This practice is followed in the Supreme Court of Victoria.[38] As Bell J put it in Shaw v Yarranova Pty Ltd, judicial responsibility

is not performed where [a] judge fails to determine the matter personally, preferring instead simply to follow an earlier decision on point of another member of the court.

On the other hand, where there is such a decision on point, the judge does not start writing on a blank page. Proper regard must be given to the previous judgment. Considerations of comity require the previous decision to be followed unless the judge attains a higher than usual standard of conviction that his or her contrary conclusion is correct. The interests of justice are not served where different judges come to different conclusions on the same question according to reasoning that appears to be entirely subjective.[39]

Hierarchical citations are citations to a court situated above the citing court in the judicial hierarchy. The Full Court of the Supreme Court of Victoria is bound by the ratio decidendi of decisions of the High Court of Australia, while obiter dicta of the High Court will be cited as being highly persuasive.[40] Prior to the enactment of the Australia Acts in 1986,[41] decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council were also binding upon the Full Court. Since the commencement of the Australia Acts, the state appellate courts are no longer bound to follow decisions of the Judicial Committee.[42]

The position is less clear with respect to decisions of the Judicial Committee made prior to the enactment of the Australia Acts. In Hawkins v Clayton, McHugh JA expressed the view that state Supreme Courts are no longer bound to follow decisions of the Judicial Committee given either before or after the commencement of the Acts.[43] This conclusion relied upon an extrapolation of the High Court’s decision in Viro v The Queen.[44] However, academic commentators have questioned this view. Tony Blackshield suggests that the preferable interpretation of Viro v The Queen is that decisions of the Judicial Committee decided prior to 1986 continue to bind the state Supreme Courts until the High Court decides otherwise.[45] In R v Judge Bland; Ex parte Director of Public Prosecutions (Vic) a single judge of the Supreme Court of Victoria followed a decision of the Full Court that had been overruled by a decision of the Judicial Committee decided prior to 1986.[46] The judge considered that the authority of the Full Court decision had been ‘revived’ by the Australia Acts.[47]

Coordinate citations are citations to other courts on the same tier in the court hierarchy. These citations are persuasive rather than binding sources of precedent. In the Supreme Court of Victoria, coordinate citations comprise citations to other intermediate appellate courts, such as the Supreme Courts of other Australian states and territories. The accepted position in Australia is that an intermediate appellate court is not bound by the decision of another intermediate appellate court, but will follow the decision of another intermediate appellate court unless convinced the decision is wrong.[48] Two related considerations underpin this principle.[49] First, there is a need for a consistent approach across Australia when decisions concern the effect of a Commonwealth Act or uniform legislation. Secondly, there should be consistency in the development of the common law throughout Australia.

Deference citations are citations to decisions of courts that are not part of the immediate judicial hierarchy, but still have persuasive value. Citations to decisions of English courts, including the House of Lords, English Court of Appeal and Judicial Committee after 1986, as well as decisions of courts in other common law jurisdictions such as New Zealand and the US, are examples. For a long time, English decisions were followed as a matter of course by state Supreme Courts. As recently as the mid‑1970s, Justices of the High Court asserted that in the absence of High Court authority, the state Supreme Courts should follow decisions of the English Court of Appeal and House of Lords.[50] This situation has since changed; the Australia Acts were the catalysts of efforts to develop an Australian common law that is suited to Australian conditions and circumstances. The relevance of English case law to Australia has been eroded, initially by the United Kingdom’s membership of the Council of Europe and European Union, and more recently by the increasing influence of European law on UK cases, in the form of instruments such as the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms[51] and its adoption in the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK) c 42.[52] In Cook v Cook, the High Court stated that while ‘courts [in Australia] will continue to obtain assistance and guidance from the learning and reasoning of the United Kingdom courts’, those decisions ‘are useful only to the degree of the persuasiveness of their reasoning’.[53] Writing extra‑curially in the wake of the commencement of the Australia Acts, Sir Anthony Mason stated:

There is … every reason why we should fashion a common law for Australia that is best suited to our conditions and circumstances. In deciding what is law in Australia we should derive such assistance as we can from English authorities. But this does not mean we should account for every English decision as if it were a decision of an Australian court. The value of English judgments, like Canadian, New Zealand and, for that matter, United States judgments, depends on the persuasive force of their reasoning.[54]

This statement reflects the practice in the Supreme Court of Victoria, which regards decisions of courts in the UK as persuasive, but is prepared to depart from them.[55] As Winneke ACJ put it in R v Parsons:

A decision of the House of Lords, although not binding on this court, has none the less always been regarded as highly persuasive. However, unless the court is persuaded they are clearly wrong, it should be prepared to follow its own established authorities and practices even if, by doing so, it might result in a departure from a contrary opinion of the House of Lords.[56]

Secondary authorities are not binding on any court, but previous studies have identified several reasons why judges refer to them in their written reasons.[57] One reason is convenience. Secondary authorities often contain lists of cases that judges find convenient to adopt. In this manner, journal articles and textbooks act as de facto digests of case law, and citing the secondary authority provides a convenient shorthand alternative to listing the cases. A second reason for citing secondary authorities is to draw on academic opinion expressed in journal articles and learned texts to explore the origins of legal principles. A third reason is to draw on the opinion of academic writers to assist judges in ascertaining what earlier cases decided. A fourth reason is that citing secondary authorities may allow a judge to refer to the views of particularly well‑respected academics or even judges writing extra‑curially to provide corroborating opinion for the position he or she has reached. Judges will be more likely to adopt this course if there is only scant case law on point. Fifthly, secondary authorities are sometimes cited because they have been approved in previous cases as correctly stating the law. In such cases, ‘the fact of citation gives a work authority to some degree and it will thus exert some influence on the way the law grows’.[58] Sixthly, secondary authorities are cited to examine the ‘legislative facts’ or ‘policy rationale’ that underpin legal rules. Much citation of social science and other non‑legal secondary authorities falls into this category.

Judges differ on how appropriate it is to cite secondary authorities in written reasons. In the US, where citation to secondary authorities in the Courts of Appeal and Supreme Court is prevalent, judges of the stature of Benjamin Cardozo, Charles Hughes and Earl Warren have spoken in glowing terms of the value of legal periodicals and their willingness to draw on them in formulating their opinions.[59] Cardozo J pioneered the citation of law reviews in the US. In the 1920s and 1930s, Cardozo J had over three times as many citations to secondary authorities as his contemporaries on the New York Court of Appeals and his propensity to cite law reviews in his opinions was not rivalled until the 1980s and 1990s.[60]

In the UK, Lord Denning commented favourably six decades ago upon the value of citing academic authorities in written reasons.[61] More recently in the House of Lords in Hunter v Canary Wharf Ltd,[62] Lords Cooke and Goff expressed divergent views on the value of citing secondary authorities. Lord Cooke considered citation to secondary authorities to be useful when the law was unsettled, while Lord Goff found the relevant secondary authorities to be of little or no value.[63]

In Canada, debate on the value of citing legal periodicals was sparked by an article written by G V V Nicholls in 1950 in response to Rinfret CJ’s refusal to recognise the Canadian Bar Review as an authority in a hearing in the Supreme Court of Canada.[64] The position of that Court has long since changed and it now readily cites secondary authorities.[65] Canadian judges, such as Justice Michael Bastarache of the Supreme Court of Canada, have argued that widespread citation of academic authorities in judgments is a positive development.[66] However, in a critique of Nicholls’ 1950 article, J E Cote, a Judge of the Alberta Court of Appeal, has argued that the Supreme Court of Canada has gone too far in citing academic authority, and that it is not sufficiently selective in weighing up which academic authorities contain analysis worth citing.[67]

Most Australian judges who have expressed a view on citing academic authorities in reasons for decision have been in favour of the practice or at least accepting of it. Several High Court justices have expressed the view that judicial recourse to journal articles and other academic writings is a useful practice, including Sir Owen Dixon,[68] Sir Frank Kitto,[69] Sir Gerard Brennan,[70] Sir Anthony Mason[71] and Michael Kirby.[72] Others, such as Sir Victor Windeyer, while not directly and explicitly commenting on the merits of citing secondary authority, have given the practice their de facto approval by virtue of extensive citation to secondary authorities in their judgments.[73] One ‘dissenting’ Australian judicial voice is Sir Garfield Barwick, who expressed the extra‑curial view that citing academic authors lessened the authority of the judgment and, as such, is a practice to be avoided as much as possible. His Honour’s view is that

citation of [academic writers], however eminent and authoritative, might reduce the authority of the judge and present him as a research student recording by citation his research material. … [In these circumstances, written reasons] become an exercise in essay writing rather than the statement of reason for an authoritative judgment.[74]

The cases considered by this article’s study are decisions of the Supreme Court of Victoria reported in the Victorian Reports sampled at 10‑year intervals from 1905 to 2005. This sample comprises 856 cases. The study does not consider unreported cases. This is consistent with previous studies of the citation practice of courts in Australia, Canada, NZ and the US. In recent years about one‑fifth of all Full Court decisions have been reported.[75] Thus, only a relatively small number of cases are actually reported in the Victorian Reports. In Canada, the comparable figure for the provincial courts of appeal is one‑sixth.[76] One reason not all cases have been reported in the authorised reports in recent times is the proliferation of specialist report series, which can be more suitable for many cases. One example is the Victorian Administrative Reports. These contain many notable administrative law cases that do not make it into the Victorian Reports. One suspects that the decision to include an administrative law case in the Victorian Reports is influenced by the knowledge that, if it is not, it will certainly be published in the Victorian Administrative Reports. The Australian Criminal Reports serve a similar function for criminal cases.

The main justification for restricting the sample to cases reported in the Victorian Reports is pragmatic in that it ensures the data collection is manageable. Nevertheless, the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria selects cases for inclusion in the Victorian Reports on the basis of their precedential value. Thus, there is also an argument that, subject to the point above about the proliferation of specialist reports, these ‘cases probably include a high proportion of all the decisions sufficiently important to call for reasoned judgment based on authority’.[77] Failure to consider unreported cases and cases reported in specialist reports, however, is a limitation. We might miss some important cases reported in the specialist reports and we cannot compare citation practice between reported and unreported cases.

All citations to case law and secondary authorities in the sample cases were counted. Citations to constitutions, regulations and statutes were excluded on the basis that the subject matter of the case dictates the citation of these sources and, as such, it is not an exercise of judicial discretion.[78] If a case or secondary authority received repeat citations in the same paragraph it was counted only once, but if it was cited again in a subsequent paragraph it was counted each time on the basis that the source was being cited for a different proposition and hence had separate significance.[79] The citation counts are weighted in the sense that the number of citations in each joint judgment was multiplied by the number of participating judges when calculating the total citation count. However, if Justice A concurred with Justice B and Justice B cited authorities, Justice A was not attributed with having cited those authorities.[80]

Citations to judgments of lower courts in the same case were not counted. If a judgment was quoted from another case that contained citations, the quoted case was counted as a citation but not the cases cited in the quoted judgment. No distinction was made between citations in the text of a judgment and citations in footnotes to a judgment because this is a matter of reporting convention which has varied over time. No distinction was made between positive and negative citations. One reason for this is that irrespective of whether an authority is cited with approval or disapproval, it is still considered sufficiently important for the judge to cite it. Since citation is an act of judicial discretion, the judge is free not to cite it at all if the authority has no influence on the judge’s thinking.[81] Secondly, unlike academic citations, few judicial citations are critical.[82] For example, McCormick found that in the Supreme Court of Canada less than one per cent of judicial citations are negative.[83]

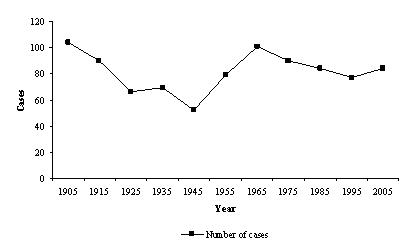

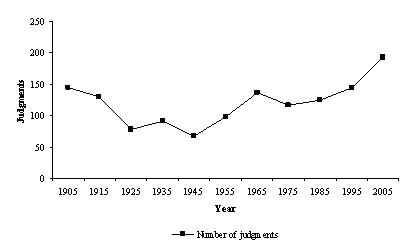

Figure 1 shows the number of cases reported in the Victorian Reports at 10‑year intervals between 1905 and 2005. In most of the sample years the reports covered between 70 and 100 cases. The largest number of cases were reported in 1905 (104) and 1965 (101) and the smallest number of cases were reported in 1945 (52). Figure 2 shows that the number of judgments traces a scalloped pattern, with the largest numbers of judgments reported at opposite ends of the time spectrum: 1905 (145), 1915 (13), 1995 (144) and 2005 (192). A spike with 136 reports occurred in 1965. The number of single‑authored judgments remained fairly steady over the period, in the range of 70–80 per cent of judgments delivered. There has, however, been a sharp increase in the number of short concurring judgments (less than a quarter of a page in length) over the last three decades of the sample period. The proportion of short concurring judgments declined from 7.6 per cent in 1905 to less than 5 per cent in 1935, 1945 and 1955. However, in 1985 that proportion had risen to 12.1 per cent of judgments, and continued to increase sharply to 18.8 per cent in 1995 and further to 31.7 per cent in 2005. The recent increase in concurring judgments has been at the expense of a decline in joint judgments. In 1975, 18.1 per cent of judgments were joint judgments, but three decades later this figure had fallen to 5.7 per cent in 2005.

Figure 1 — Number of Cases

Figure 2 — Number of Judgments

Table 1 shows the case load of the Court over time. The highest proportion of cases heard by the Court dealt with criminal law, evidence and procedure, property law, statutory interpretation and wills and probate. These five areas of law constituted a clear majority of the sampled cases heard by the Supreme Court. Robert Kagan and his colleagues found that the case load of state Supreme Courts in the US changed over the century 1870–1970.[84] In particular, their study observed a substantial increase in administrative, criminal and tort law cases and a decline in commercial and property law cases.[85] Their explanation for this secular change in the composition of the courts’ workloads is that the resolution of commercial law matters has shifted from ‘the upper reaches of the court system to other branches and levels of government’ while there has been an increase in ‘the confrontation between citizen and state’.[86] The present data also reveal a sustained increase over the observation period in criminal law matters in the Supreme Court of Victoria, though there is no upward trend in administrative and tort law cases.

Table 1 — Subject Matter of Reported Cases in the Supreme Court of Victoria

|

Area of law

|

1905

|

1915

|

1925

|

1935

|

1945

|

1955

|

1965

|

1975

|

1985

|

1995

|

2005

|

Total

|

|

Wills/probate

|

18

|

14

|

10

|

9

|

10

|

10

|

12

|

7

|

1

|

5

|

3

|

99

|

|

Criminal

|

1

|

7

|

4

|

6

|

7

|

11

|

17

|

20

|

13

|

17

|

37

|

140

|

|

Constitutional

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

1

|

5

|

|

Property

|

7

|

12

|

13

|

8

|

11

|

19

|

9

|

11

|

8

|

10

|

5

|

113

|

|

Contracts

|

1

|

5

|

7

|

2

|

3

|

5

|

7

|

6

|

6

|

1

|

2

|

45

|

|

Procedure

|

29

|

18

|

6

|

2

|

4

|

5

|

8

|

14

|

15

|

15

|

7

|

123

|

|

Torts

|

2

|

3

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

5

|

2

|

3

|

5

|

33

|

|

Taxation

|

11

|

8

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

30

|

|

Statute

|

10

|

7

|

9

|

22

|

8

|

6

|

7

|

4

|

12

|

15

|

9

|

109

|

|

Insurance

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

4

|

0

|

2

|

10

|

|

Administrative

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

8

|

4

|

8

|

1

|

4

|

31

|

|

Industrial

|

3

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

14

|

|

Family

|

6

|

7

|

7

|

9

|

4

|

7

|

9

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

53

|

|

Trusts

|

2

|

4

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

5

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

19

|

|

Jurisdiction

|

3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

8

|

|

Customs

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

International

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

4

|

|

Company

|

8

|

1

|

5

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

13

|

6

|

8

|

4

|

3

|

56

|

|

Damages

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

|

Total

|

104

|

90

|

66

|

69

|

52

|

79

|

101

|

89

|

84

|

77

|

84

|

895

|

The confrontation between citizen and state of which Kagan and his colleagues wrote has not played out in the Supreme Court of Victoria. There has been no increase in administrative law matters for three reasons. First, many such matters come through the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’), the President of which is a Supreme Court judge. Many decisions of importance in VCAT are decided by the President. They are, therefore, likely to be heard originally by a Supreme Court judge (albeit as President of VCAT). The status of the President may influence the lack of appeals to the Court of Appeal. Secondly, the Administrative Law Act 1978 (Vic) has not proven an attractive vehicle to encourage judicial review. It has many procedural limits, notably an inflexible time limit that cannot be extended by the Court.[87] Thirdly, the early creation of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (‘AAT’), which later became the VCAT, introduced a wide right of merits review in Victoria from 1984. This probably precluded many applications for judicial review that would otherwise have been made. In effect, this mechanism for administrative review has directed most administrative law challenges away from the Supreme Court.

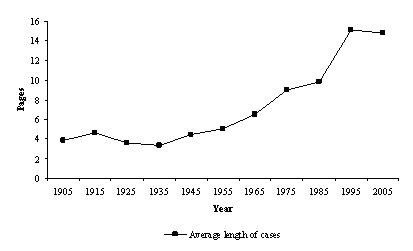

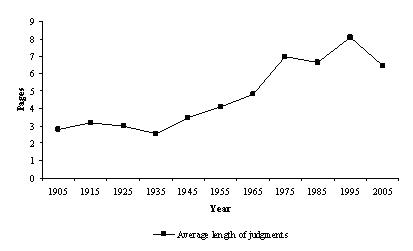

Figures 3 and 4 show the average length of cases and the average length of individual judgments (both measured in numbers of pages) for reported cases and judgments in each of the sampled years. The average length of both reported cases and judgments displays a sustained upward trend over the course of the century but falls off in the last decade of the observation period. The pronounced dip in the average length of judgments in 2005 reflects the sharp increase in the proportion of short concurring judgments in that year. Notwithstanding the 20 per cent drop in the last decade, the average length of judgments has increased by 141 per cent over the entire sample period. The average length of reported judgments in 1905 was 2.7 pages and by 1995 this had increased to 8.1 pages; even in 2005 it was still 6.5 pages. The average length of reported cases increased almost threefold over the century, by 280 per cent, from 3.9 pages in 1905 to 14.8 pages in 2005. An increase in the average length of cases and judgments has also been observed in decisions of the High Court of Australia,[88] the English Court of Appeal,[89] and the US state Supreme Courts.[90]

Friedman and his colleagues suggest some explanations for the increase in the length of opinions in the US state Supreme Courts, which are also applicable to the Supreme Court of Victoria.[91] First, with each passing year the Court has more of its own law to discuss and be cited. Secondly, from a broader policy perspective, the acceleration in social change has intensified the struggle between competing interest groups and increased demands on the courts to be seen to be administering due process. Jean Louis Goutal argues that one of the major drivers of longer judgments in the English Court of Appeal throughout the 20th century is that judges have laboured to adapt earlier precedents to changed economic and political conditions.[92] Thirdly, over the last two decades or so the information technology revolution has made it much easier to prepare judgments. Changes in information technology have altered the mechanical aspects of the preparation of judgments and the ease of accessing authorities that can be cited in them. For example, free online services such as AustLii and various subscription‑based online services, such as LexisNexis and Westlaw, provide wider access to case histories and authorities.[93] Fourthly, it is likely that the creation of a permanent Court of Appeal in 1995 contributed to longer judgments. The Court of Appeal has dedicated researchers (the Supreme Court has a few, but not as many). The changes in information technology have worked in conjunction with the Court’s increased ability to call upon these added resources, to generate greater citation of authorities and longer judgments.

Figure 3 — Average Length of Cases

Figure 4 — Average Length of Judgments

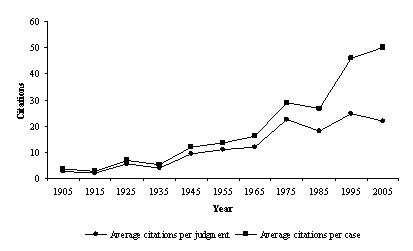

Figure 5 provides an overview of citation patterns on the Supreme Court of Victoria over the course of the last century, sampled at 10‑year intervals. There has been a positive trend in both the average number of citations per judgment and the average number of citations per case. In 1905, the average number of citations per judgment was 2.50[94] and the average number of citations per case was 3.49. In 2005, the average number of citations per judgment was 21.96 and the average number of citations per case was 50.20. The cumulative increase in the average number of citations amounts to 780 per cent with respect to judgments and 1340 per cent with respect to cases.

This tendency for courts to cite more authorities over time has also been observed in the few studies of citation practice of courts in the US that have adopted a long time horizon. For example, William Manz found that average citations in majority opinions on the New York Court of Appeals increased from 5.4 to 12.4 between 1850 and 1980.[95] Friedman and his colleagues found that average citations in ‘routine opinions’ in US state Supreme Courts increased from 3.2 in 1870–80 to 9.4 in 1960–70.[96]

Figure 5 — Average Number of Citations

Table 2 shows the types of authorities the Supreme Court of Victoria has cited during the sample years. The following discussion examines general trends in the citation practice of the Court over time in more detail in terms of the taxonomy of citations identified above; namely, consistency citations, hierarchical citations, coordinate citations, deference citations and citations to secondary authorities.

Table 2 — Citations in Reported Cases in the Supreme Court of Victoria

|

|

1905

|

1915

|

1925

|

1935

|

1945

|

1955

|

1965

|

1975

|

1985

|

1995

|

2005

|

|

Total cases

|

104

|

90

|

66

|

69

|

52

|

79

|

101

|

90

|

84

|

77

|

84

|

|

Total judgments

|

145

|

130

|

78

|

91

|

67

|

97

|

136

|

116

|

124

|

144

|

192

|

|

High Court

|

|||||||||||

|

1903–19

|

3

|

29

|

21

|

10

|

7

|

11

|

18

|

76

|

33

|

27

|

38

|

|

1920–39

|

–

|

–

|

13

|

13

|

25

|

35

|

53

|

77

|

41

|

42

|

83

|

|

1940–59

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

7

|

53

|

195

|

159

|

92

|

103

|

74

|

|

1960–79

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

39

|

206

|

156

|

212

|

140

|

|

1980–99

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

101

|

714

|

759

|

|

2000–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

222

|

|

Subtotal

|

3

|

29

|

34

|

23

|

39

|

99

|

305

|

518

|

423

|

1098

|

1316

|

|

Average per case

|

0.03

|

0.32

|

0.52

|

0.33

|

0.75

|

1.25

|

3.02

|

5.76

|

5.04

|

14.26

|

15.67

|

|

Average per judgment

|

0.02

|

0.22

|

0.44

|

0.25

|

0.58

|

1.02

|

2.24

|

4.47

|

3.41

|

7.63

|

6.85

|

|

Federal Court

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

3

|

25

|

79

|

77

|

|

Supreme Court of Victoria

|

|||||||||||

|

Total citations

|

132

|

38

|

67

|

41

|

94

|

173

|

336

|

556

|

433

|

738

|

1184

|

|

Average per case

|

1.27

|

0.42

|

1.02

|

0.59

|

1.81

|

2.19

|

3.33

|

6.18

|

5.15

|

9.58

|

14.10

|

|

Average per judgment

|

0.91

|

0.29

|

0.86

|

0.45

|

1.40

|

1.78

|

2.47

|

4.79

|

3.49

|

5.13

|

6.17

|

|

Supreme Courts of other states

and territories

|

|||||||||||

|

Tasmania

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

4

|

3

|

9

|

4

|

12

|

5

|

|

NSW

|

1

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

18

|

47

|

53

|

113

|

126

|

237

|

416

|

|

Queensland

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

6

|

10

|

41

|

27

|

92

|

95

|

|

WA

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

26

|

53

|

|

SA

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

11

|

11

|

18

|

16

|

38

|

70

|

|

Northern Territory

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

1

|

10

|

5

|

|

ACT

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

4

|

4

|

14

|

|

Subtotal

|

1

|

5

|

3

|

5

|

27

|

69

|

80

|

185

|

183

|

419

|

658

|

|

Other courts

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

9

|

15

|

11

|

7

|

8

|

108

|

|

English courts

|

|||||||||||

|

House of Lords

|

30

|

11

|

21

|

16

|

65

|

46

|

128

|

143

|

169

|

244

|

92

|

|

Judicial Committee

|

15

|

7

|

13

|

14

|

77

|

29

|

44

|

77

|

62

|

71

|

29

|

|

Court of Appeal

|

41

|

39

|

97

|

94

|

99

|

208

|

231

|

305

|

286

|

281

|

220

|

|

Lower courts

|

104

|

86

|

139

|

114

|

120

|

266

|

319

|

444

|

313

|

183

|

190

|

|

Subtotal

|

190

|

143

|

270

|

238

|

361

|

549

|

722

|

969

|

830

|

779

|

531

|

|

Average per case

|

1.83

|

1.59

|

4.09

|

3.45

|

6.94

|

6.95

|

7.15

|

10.77

|

9.88

|

10.12

|

6.32

|

|

Average per judgment

|

1.31

|

1.10

|

3.46

|

2.62

|

5.39

|

5.66

|

5.31

|

8.35

|

6.69

|

5.41

|

2.77

|

|

Other countries

|

6

|

2

|

22

|

7

|

39

|

64

|

30

|

82

|

69

|

180

|

56

|

|

Secondary sources — legal

|

|||||||||||

|

Books

|

30

|

19

|

33

|

33

|

45

|

78

|

91

|

201

|

173

|

93

|

175

|

|

Periodicals

|

0

|

4

|

4

|

12

|

9

|

16

|

17

|

28

|

29

|

4

|

6

|

|

Encyclopaedias

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

|

Law reform reports

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

15

|

21

|

15

|

|

Dictionaries

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

3

|

7

|

1

|

|

Other

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

6

|

12

|

18

|

30

|

95

|

66

|

|

Subtotal

|

30

|

24

|

38

|

45

|

58

|

101

|

121

|

251

|

251

|

221

|

263

|

|

Secondary sources — non‑legal

|

|||||||||||

|

Books

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Periodicals

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Dictionaries

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

4

|

5

|

2

|

13

|

6

|

13

|

23

|

|

Other

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Subtotal

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

1

|

6

|

5

|

2

|

13

|

6

|

13

|

24

|

|

Total

|

363

|

242

|

437

|

360

|

624

|

1069

|

1611

|

2588

|

2227

|

3535

|

4217

|

|

Average citations per judgment

|

2.50

|

1.86

|

5.60

|

3.96

|

9.31

|

11.02

|

11.85

|

22.31

|

17.96

|

24.55

|

21.96

|

|

Average citations per case

|

3.49

|

2.69

|

6.62

|

5.22

|

12.00

|

13.53

|

15.95

|

28.76

|

26.51

|

45.91

|

50.20

|

Studies of courts in Australia, Canada and NZ have found that hierarchical citations form the highest proportion of judicial citations, followed by consistency citations.[97] Studies for the US have found that consistency citations form the largest share of total citations, followed by hierarchical citations.[98] Consistency and hierarchical citations are the two most important forms of citation in the Supreme Court of Victoria. There has been a general upward trend in the average number of both types of citation. In 1905, the average numbers of citations per judgment and per case to previous decisions of the Supreme Court of Victoria were 0.91 and 1.27, respectively. There was a slight dip in the following decades (1915–35), but they have followed a positive trajectory ever since. In 2005, the average numbers of citations per judgment and per case to previous decisions of the Supreme Court of Victoria had increased to 6.17 and 14.10, respectively. In 1905, the average numbers of citations on a per judgment and per case basis to the High Court were just 0.02 and 0.03, but by 2005, the comparable figures were 6.85 and 15.67.

While the average number of consistency and hierarchical citations on a per case and per judgment basis have increased over time, hierarchical citations to the High Court have become more important than consistency citations to the Supreme Court’s own previous decisions. In 1905, the highest proportion of the Supreme Court’s citations were consistency citations, but by 2005 the highest proportion of the Court’s citations were hierarchical citations. In 1905, 36.4 per cent of the Court’s citations were to its own previous decisions, but by 2005 this figure had fallen to 28.1 per cent.

In 1905, just 0.8 per cent of the Court’s citations were to decisions of the High Court, less than the Judicial Committee (4.1 per cent), the House of Lords (8.3 per cent) and the English Court of Appeal (11.3 per cent). Of course, it may reasonably be argued that we do not learn much from examining the Court’s citations to decisions of the High Court in 1905 given that 1904 was the High Court’s first full year of operation and, as a consequence, there were few High Court cases to cite. Thus, if we take 1915 as a starting point, after a decade of High Court jurisprudence the High Court accounted for 12 per cent of the Court’s citations, which was more than either the Judicial Committee or the House of Lords, but still less than citations to the English Court of Appeal. In fact, it was not until 1965 that the Supreme Court of Victoria cited the High Court more than the English Court of Appeal. There are at least two reasons for this phenomenon. The first is that there is a large stock of English Court of Appeal cases to cite, while it has taken time for the body of High Court cases to develop. The other reason is the important place that decisions of English courts have occupied as sources of authority in the Australian court structure for most of the century under consideration. Four decades after the High Court first overtook the English Court of Appeal as a source of authority for the Supreme Court of Victoria, the High Court’s position at the apex of the court hierarchy in Australia was firmly entrenched. By 2005, hierarchical citations to the High Court were almost one‑third of total citations, clearly higher than any other single court.

The other noticeable feature of Table 2 with respect to hierarchical citations is that the Supreme Court favours more recent High Court cases. In 2005, the Court cited 759 High Court cases decided between 1980 and 1999; 140 High Court cases decided between 1960 and 1979; 74 High Court cases decided between 1940 and 1959, and so on. The same decline in citation to earlier High Court cases is observed in the other sample years, at least back to 1955. Previous studies have observed that precedent has a citation half‑life. Put formally, the citation half‑life is the probability that citation of a case by the Court is reduced by 50 per cent every x years.[99] The practical implication of a case having a citation half‑life is that the probability that it will be cited declines as it gets older. There are several reasons for the decline in the citation power of precedent over time.[100] First, later cases may be more relevant on the facts because the social context of earlier cases has changed. Secondly, the stock of older precedent will be reduced over time as earlier cases are overruled by later cases or statutes. Thirdly, legal opinion may have changed so that even if the earlier cases are not overruled, their reasoning may be regarded as less persuasive.

There has been an increase in the proportion of coordinate citations over the last two decades, after having very low citation rates for most of the last century. For the first four decades of the study (1905–35) coordinate citations formed a miniscule proportion of the Supreme Court’s citations and most coordinate citations were to the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Between 1945 and 1985, coordinate citations hovered around 5–6 per cent of the Court’s citations in most sample years and did not rise above 10 per cent. In 1995, coordinate citations exceeded 10 per cent of citations (11.9 per cent) for the first time and by 2005, coordinate citations represented 15.6 per cent of the Court’s citations. The figure for 1995 is similar to the finding from the previous study of the Court’s citation practice that coordinate citations accounted for 13.3 per cent of the Court’s total citations in 1990.[101] The 2005 figure is very close to the estimate that coordinate citations in the Supreme Court of Victoria constitute 15.9 per cent of citations, based on the 50 most recent reported cases as at June 1999.[102]

The NSW Supreme Court is the source of the overwhelming majority of coordinate citations. From 1905 to 1935 all but one coordinate citation was to that Court. Since 1945, citations to that Court have consistently accounted for approximately two‑thirds of coordinate citations, with a slight dip in 1995 when they accounted for 56 per cent of coordinate citations. One explanation for the dominance of NSW is that, once cited, there is a flow‑on effect. Peter Harris has argued that once a case from one state court is cited by another state court, it becomes ‘part of the common law of the [citing state]’ and the probability that an out‑of‑state court would cite it again increases accordingly.[103] Another explanation for the prevalence of citations to the NSW Supreme Court is the social proximity of the states. Merryman argued that the Supreme Court of California cited the Supreme Courts of some states more than others because the social context of litigation in some states was closest to California.[104] Because Victoria and NSW are geographically proximate and have a similar industrial base, it might be argued that Victoria has more in common with NSW than, say, Western Australia, which is on the other side of the country and heavily reliant on agricultural and mining industries.[105] South Australia is geographically proximate to Victoria, but is much less industrial than Victoria or NSW. NSW and Victoria have also experienced quite different immigration patterns from SA and WA.

Previous studies have also found that the NSW Supreme Court is cited more than the other state or territory Supreme Courts.[106] For example, the Supreme Court of WA cites the NSW Supreme Court far more frequently than it cites the Supreme Court of SA.[107] Thus, there seem to be other considerations at play, apart from the geographical and economic proximity of the states. Another reason for the high proportion of coordinate citations to the NSW Supreme Court is the prestige of that Court relative to other state Supreme Courts. NSW has the largest population of any state in Australia. Friedman and his colleagues found that the Supreme Court of California was cited much more often than the Supreme Courts of states such as Alaska and Hawaii. Their explanation was that California had a much larger population than these states; therefore, the decisions of the Supreme Court of California carried more weight.[108] NSW also has the biggest economy of any state in Australia.[109] Reflecting the importance of its economy, more commercial cases are commenced in NSW than all other Supreme Courts combined. Overall, about two‑thirds of commercial litigation in Australia is commenced in NSW. There are also parallels here with California, which has the eighth largest economy in the world, about three‑fifths the size of China’s, and larger than the economies of Brazil and Canada.[110] Thus, the economic impact of decisions in both states is likely to be considerable, with spillover effects to other states.

The NSW Bar has produced the highest number of appointments to the High Court[111] and Bert Evatt became Chief Justice of the NSW Supreme Court following his Honour’s retirement from the High Court. The NSW Supreme Court, along with the Supreme Court of Victoria, has a reputation for innovation among the state Supreme Courts. This is consistent with US evidence that the state Supreme Courts which have reputations for doctrinal leadership, such as California, Massachusetts, New York and Washington state, receive more out of court citations than other state Supreme Courts, holding sociocultural factors constant.[112] In Canada, the Ontario Court of Appeal is the equivalent of the NSW Supreme Court in Australia. Such has been the dominance of the Ontario Court of Appeal in receiving coordinate citations from the other provincial courts of appeal in Canada that McCormick has dubbed it a junior Supreme Court of Canada.[113]

A noticeable feature of Table 2 is the importance of deference citations to decisions of the English courts for most of the century. Citations to decisions of English courts only begin to fall following the commencement of the Australia Acts and subsequent calls for building an Australian common law. On an average per judgment and average per case basis, citations to English courts as a whole were higher than citations to the High Court up to and including 1985, and citations to English courts as a whole were higher than citations to the Court’s own previous decisions for all years except 2005. In 1985, citations to English cases accounted for 37 per cent of all citations; following the commencement of the Australia Acts this fell to 22 per cent of all citations in 1995 and 13 per cent in 2005. The decline in the proportion of English cases cited by the Supreme Court of Victoria is similar to what has occurred in the provincial courts of appeal in Canada. McCormick found that English courts account for about 15 per cent of citations in the provincial courts of appeal in Canada.[114] By contrast, the state Supreme Courts in the US hardly cite any English cases at all.[115]

The House of Lords, English Court of Appeal and lower English courts were cited more than the Judicial Committee, though the Judicial Committee sat at the apex of the Australian court hierarchy for much of the period of the study. Previous studies have also found that state and territory Supreme Courts in Australia cite the Judicial Committee less than other English courts.[116] This finding is replicated for the High Court,[117] the NZ Court of Appeal[118] and the provincial courts of appeal in Canada.[119] One explanation for this finding is that there are relatively few decisions of the Judicial Committee to cite. Even when the Judicial Committee was in its heyday prior to abolition of appeals from the Supreme Court of Canada in 1949, when it sat at the pinnacle of the judicial hierarchy in Australia, Canada and NZ, relatively few cases made it to the Judicial Committee.[120] Following the abolition of appeals to the Judicial Committee from Australia, NZ was the only significant Commonwealth country to retain appeals. In 2003, NZ abolished appeals to the Judicial Committee, leaving only 11 mainly Caribbean and small island states that retain final appeal to the Judicial Committee.[121]

Another possible explanation for the small number of citations to the Judicial Committee relative to the House of Lords is that the Judicial Committee has sometimes been regarded as producing decisions of dubious quality.[122] It has been suggested that the Judicial Committee is the poor cousin of the House of Lords.[123] A prominent critic of the Judicial Committee (albeit largely in private) was Sir Owen Dixon, who was scathing in his Honour’s diaries and private correspondence to contemporaries such as Chief Justice John Latham of the lack of understanding exhibited by the English Law Lords in the disposition of British Commonwealth cases.[124]

The reduced stock of cases to cite as one moves up the court hierarchy also explains why the Supreme Court of Victoria cites more lower court English decisions than decisions of the English Court of Appeal and more decisions of the English Court of Appeal than the House of Lords for much of the period. The Court would presumably cite a decision of the House of Lords or Judicial Committee in preference to that of the Queen’s Bench or Chancery Division if one was on point, but often there is no such decision. The English High Court and Court of Appeal have traditionally heard most probate and trust matters (which rarely reach the House of Lords) and many criminal law cases (which did not appear in the House of Lords in great numbers until the 1970s). These are two areas that occupied a large part of the jurisdiction of Australian state courts.

To summarise, for a large part of the 20th century, Australian state courts cited English cases because:

1 the law of Australia and England was largely comparable;

2 there were many useful precedents available in English cases; and

3 there was often not comparable Australian authority and, where there was, it was largely informed by the English cases.

Deference citations to courts in countries other than England have increased in absolute number over time, peaking in 1995, before falling in 2005. However, in proportional terms deference citations to courts in countries other than England remain largely inconsequential. In those years when there was a relatively high proportion of citations to courts in countries other than England, these citations accounted for at most 5–6 per cent of deference citations. In most years this sort of deference citation was responsible for 1–2 per cent of total citations. For most of the period being considered, courts in countries other than Australia and England would have been regarded as having little persuasive value. Such decisions may also have been difficult to locate.[125] The problem of easily locating such decisions has only changed relatively recently with the advent of online database services such as Westlaw. The recent increase in the propensity of the High Court to cite cases from a range of countries as part of the process of fashioning a common law suited to the needs of Australia has not had much of a ‘trickle down’ effect to the state and territory Supreme Courts.[126] In this respect, the findings in this study are consistent with previous studies for state Supreme Courts in Australia, which have found that deference citations to courts in countries other than England make up 2–3 per cent of citations.[127] Most of these deference citations were to courts in Canada, NZ and the US. Citations to courts in NZ can be explained by its geographical proximity to Australia, while Canada and the US are both common law countries with federal structures. This finding is also consistent with previous studies for the state Supreme Courts.[128]

Citations to secondary authorities have increased over time, but in 2005 they still only accounted for a relatively small proportion of the Court’s overall citations. At the end of the sample period, 6.8 per cent of the Court’s total citations were to secondary authorities, consistent with findings from previous Australian studies. The previous study of the citation practice of the six state Supreme Courts using the 50 most recent reported cases decided as of June 1999 found that 6–7 per cent of total citations were to secondary authorities.[129] This is also generally consistent with findings for the state Supreme Courts in the US. For example, Merryman, in his study of the citation practice of the Supreme Court of California in 1950, 1960 and 1970, found that secondary authorities were responsible for 7.5 per cent of total citations in 1970.[130]

Among the particular categories of secondary authorities cited, legal textbooks received the most citations, consistent with the previous study of the six Australian state Supreme Courts.[131] Legal periodicals were a clear second in most years, but were still cited relatively infrequently. Friedman and his colleagues have postulated that: ‘By citing law reviews, a court can perhaps bootleg “nonlegal” premises into its decisions, or deal with “legal” considerations broader than those usually dealt with.’[132] The High Court’s propensity to cite law reviews has increased over the last two decades.[133] It is reasonable to link this change in practice to the High Court’s adoption of a more activist stance under the leadership of Sir Anthony Mason. Certainly studies for the courts in the US have regarded propensity to cite law reviews as a barometer of judicial activism.[134] The results here suggest that the Supreme Court of Victoria is not as policy‑oriented as the High Court. This is a reflection of the status of the Supreme Court of Victoria as an intermediate appellate court. However, given that the overwhelming majority of Victorian cases end in the Supreme Court of Victoria, it is, in some senses, a final court for the great majority of Victorian cases. Thus, it is suggested that through downplaying the policy dimension of its decisions, the Court is not as mindful as it could be of this aspect of finality in many of its decisions.

In Table 2 secondary authorities are classified as ‘legal’ or ‘non‑legal’. The Court cited very few non‑legal sources. In 2005, which is the year in which the Court cited the largest number of non‑legal secondary authorities, these authorities still accounted for just 8 per cent of secondary authorities cited and 0.5 per cent of total citations. In 2005, as in most years, the bulk of citations to non‑legal secondary authorities were citations to dictionaries. The propensity of Australian courts to cite few non‑legal secondary authorities has been observed in previous studies for the High Court[135] and the Australian state and territory Supreme Courts.[136] This practice has also been observed in studies for the state Supreme Courts in the US. Friedman et al found that ‘social science, economic or technical studies’ were cited in just 0.6 per cent of the 1940–70 cases in their sample, representing the last four decades of their study.[137] Their explanation for this result is: ‘Old habits of citation persist, no doubt because judges feel that only “legal” authorities are legitimate’.[138] In contrast, the US Supreme Court cites a much higher proportion of non‑legal secondary authorities.[139] One reason is that the Court cites a lot of social science literature in death penalty cases and in cases relating to the Bill of Rights.[140] A second reason is that the large amount of public interest litigation and amicus curiae involvement in US cases changes the nature of the material placed before the courts. Each kind of litigation almost inevitably involves either parties or issues (or both) that are much more likely to place secondary material before the courts.

Tables 3A–K present detailed information about the citation practice of individual judges in each of the sampled years. Taking a minimum of 10 judgments in any given year as a cut‑off, in the period prior to World War II the biggest citers on the Court were Madden CJ (1893–1918), Cussen J (1906–33), McArthur J (1920–34) and Martin J (1934–57). In 1905, Madden CJ cited, on average, 3.3 authorities per judgment, compared with the 1905 mean of 2.5 authorities per judgment, and was responsible for one‑third of the citations of the Court. In 1915, Madden CJ cited 2.7 authorities per judgment and Cussen J cited 2.71 authorities per judgment, compared with a 1915 average of 1.86 authorities per judgment.[141] Together Madden CJ and Cussen J were responsible for 57 per cent of the Court’s citations in 1915. In 1925, Cussen J cited 8.33 authorities per judgment, followed by McArthur J who cited 5.09 authorities per judgment. In 1925, Cussen and McArthur JJ delivered fewer than 30 per cent of the reported judgments, but were responsible for more than half of the Court’s citations. In 1935, Martin J cited 8.45 authorities per judgment. Of those judges who delivered at least 10 judgments in that year, this represents double the number of citations by the next biggest citer, Gavan Duffy J (1933–61) with 4.26 citations per judgment. In 1945, Gavan Duffy and Martin JJ were again the biggest citers on the Court, each citing over 13 authorities per judgment and together accounting for more than 50 per cent of the Court’s overall citations.

Table 3A — Citation Practice of Justices of the Supreme Court of Victoria in 1905

|

|

a’Beckett J

|

Hodges J

|

Hood J

|

Holroyd J

|

Madden J

|

Total

|

|

Total judgments

|

38

|

39

|

49

|

26

|

37

|

189

|

|

High Court

|

||||||

|

1903–19

|

–

|

3

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

3

|

|

1920–39

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

1940–59

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

1960–79

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

1980–99

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

2000–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

Subtotal

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

|

Average[142]

|

–

|

0.08

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

Supreme Court of Victoria

|

||||||

|

Subtotal

|

16

|

11

|

21

|

5

|

79

|

132

|

|

Average

|

0.42

|

0.28

|

0.43

|

0.19

|

2.14

|

|

|

Other state and territory Supreme

Courts

|

||||||

|

NSW

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

1

|

1

|

|

Tasmania

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Queensland

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

WA

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

SA

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Subtotal

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

|

English courts

|

||||||

|

House of Lords

|

9

|

8

|

10

|

–

|

3

|

30

|

|

Judicial Committee

|

4

|

2

|

6

|

1

|

2

|

15

|

|

Court of Appeal

|

10

|

9

|

12

|

5

|

5

|

41

|

|

Lower courts

|

22

|

23

|

25

|

7

|

27

|

104

|

|

Subtotal

|

45

|

42

|

53

|

13

|

37

|

190

|

|

Average

|

1.18

|

1.08

|

1.08

|

0.5

|

1

|

–

|

|

Other countries

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

6

|

|

Average

|

0.03

|

–

|

0.04

|

0.04

|

0.05

|

–

|

|

Secondary sources — legal

|

||||||

|

Books

|

11

|

9

|

8

|

–

|

2

|

30

|

|

Periodicals

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Encyclopaedias

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Law reform reports

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Dictionaries

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Other

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Subtotal

|

11

|

9

|

8

|

0

|

2

|

30

|

|

Average

|

0.29

|

0.23

|

0.16

|

–

|

0.05

|

–

|

|

Secondary sources — non‑legal

|

||||||

|

Books

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Periodicals

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Dictionaries

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

1

|

1

|

|

Other

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Subtotal

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

|

Average

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0.03

|

–

|

|

Total

|

73

|

65

|

84

|

19

|

122

|

363

|

|

Average

|

1.92

|

1.67

|

1.71

|

0.73

|

3.30

|

–

|

Table 3B — Citation Practice of the Supreme Court of Victoria in 1915

|

|

a’Beckett J

|

Hodges J

|

Hood J

|

Madden J

|

Cussen J

|

Total

|

|

Total judgments

|

36

|

25

|

34

|

27

|

24

|

146

|

|

High Court

|

||||||

|

1903–19

|

1

|

–

|

8

|

13

|

7

|

29

|

|

1920–39

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

1940–59

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

1960–79

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

1980–99

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

2000–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

|

Subtotal

|

1

|

0

|

8

|

13

|

7

|

29

|

|

Average

|

0.03

|

–

|

0.24

|

0.48

|

0.29

|

–

|

|

Supreme Court of Victoria

|

||||||

|

Subtotal

|

6

|

1

|

9

|

9

|

13

|

38

|

|

Average

|

0.17

|

0.04

|

0.26

|

0.33

|

0.54

|

–

|

|

Other state and territory Supreme

Courts

|

||||||

|

Tasmania

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

1

|

–

|

1

|

|

NSW

|

–

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

4

|

|

Queensland

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

WA

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

SA

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

0

|

|

Subtotal

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

5

|

|

English courts

|

||||||

|

House of Lords

|